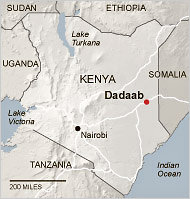

The Dadaab refugee camp complex in northeastern Kenya consists of three camps: Ifo, Hagadera and Dagahaley. The complex constitutes the largest refugee camp in the world, and it is beyond full. Originally built to house 90,000 people, the camps now house nearly 400,000 people. Nevertheless, according to MSF information, thousands of Somali refugees continue to arrive every day, fleeing the violent conflict in their home country – and devastating effects of ongoing drought and lack of food.

The Dadaab refugee camp complex in northeastern Kenya consists of three camps: Ifo, Hagadera and Dagahaley. The complex constitutes the largest refugee camp in the world, and it is beyond full. Originally built to house 90,000 people, the camps now house nearly 400,000 people. Nevertheless, according to MSF information, thousands of Somali refugees continue to arrive every day, fleeing the violent conflict in their home country – and devastating effects of ongoing drought and lack of food.

When they arrive in Dadaab, exhausted after several days or weeks of travel, new arrivals receive inadequate assistance. Because there is no room for them, they must construct and settle in makeshift shelters on the outskirts of the camp. Newly arrived refugees are forced to live in the open, on the outskirts of the camps, with no easy access to water.

Despite the fact that MSF and other international organisations have repeatedly asked for a solution to relieve pressure on the overcrowded Dadaab camps, no sufficient action has been taken.

Their situation has been made even worse by the severe drought affecting the Horn of Africa. MSF has found alarmingly high rates of malnutrition among the Somali refugees arriving and settling on the outskirts of the Dadaab camp, prompting MSF to reinforce its medical intervention there.

Kenya to open new camp, wants all refugees back to Somalia

The Kenyan authorities announced on 14 July that the Ifo II camp, which will accommodate up to 80,000 people, will open within 10 days. At the same time Kenya wants a refugee camp set up in Somalia over security fears.

Internal security assistant minister Orwa Ojodeh said refugees in Dadaab would then be moved to the camp, four kilometres into Somalia.

Mr Ojodeh said the influx of refugees into the country poses a security risk since no screening had been done on those entering Kenya.”At the moment, we may not be sure of who is a genuine refugee. We are not ready to take chances, otherwise terrorists may find their way into the country,” said Mr Ojodeh.

He further said that the Ministry of Internal Affairs was coming up with a programme that would see refugees from Somalia being ferried back to their country after a place across the border has been identified.

“The situation in Somalia is now stable; there are no more conflicts. The problem is that people are running away from famine caused by the drought. If that is the case, they don’t have to travel all the way to Kenya when food can be supplied to them near their border,” said Mr Ojodeh.

The assistant minister said they had appealed to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to identify non-governmental organisations that can supply food within Somalia.

“We know their problem is food and we will work to ensure they get it within their country,” he added.

UNHCR’s mandate does not cover internally displaced persons. It will, therefore, offer limited assistance in Somalia.

Mr Ojodeh differed with Prime Minister Raila Odinga who, on Thursday, ordered the reopening the Kenya-Somalia border to allow in Somali refugees seeking humanitarian assistance.”The official opening of the border must be deliberated and agreed on, but for now we are determined to keep these people (Somali refugees) within their borders,” said Mr Ojodeh.

Mr Odinga said the refugees were in serious need of help and Kenya could not ignore them.

Wajir South MP Mohamed Sirat agreed with Mr Ojodeh that there was no point in letting the refugees into the country. He said that the camp in Dadaab had been overwhelmed.

“When the refugees come here, they need trees to construct their houses and for firewood, and they are depleting our trees,,” Dr Sirat added.

UN delivers relief

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) said on 15 July it had airlifted emergency nutrition supplies and water equipment into Somalia, the country worst affected by a severe drought that has ravaged large swaths of the Horn of Africa, leaving an estimated 11 million people in need of humanitarian assistance.

More than half a million children in Somalia are acutely malnourished and in urgent need of humanitarian assistance. Southern Somalia is the most affected area with 80 per cent of all malnourished children living there.

The delivered consignment of relief items included five tons of essential nutrition supplies, including therapeutic food and medicines to treat severely malnourished children, and equipment to supply clean water to a camp for displaced persons in Baidoa.

Meanwhile, UNICEF Executive Director Anthony Lake, who is visiting Kenya, will at the weekend travel to the north-western district of Turkana, where malnutrition rates have risen dramatically and child mortality rates are above the emergency threshold, the agency’s spokesperson in Geneva, Marixie Mercado, told reporters.

The UN World Health Organization (WHO) said that a poor health care system in drought-affected areas of the Horn of Africa, low immunization coverage, population movements, lack of clean drinking water and poor sanitation have left people vulnerable to communicable diseases.

Extremely high malnutrition rates

A mixture of extreme heat, a lack of water and sanitation, and delays in the registration of new arrivals Dadaab refugee camp – wh ich in turn delays the provision of food rations – have resulted in extremely difficult living conditions for new arrivals.

ich in turn delays the provision of food rations – have resulted in extremely difficult living conditions for new arrivals.

During the three-day rapid nutritional assessment, the MSF team measured and weighed some 500 children between six months and five years old. As many as 37.7 percent of the children were suffering from global acute malnutrition; of these, 17.5 percent were severely malnourished and at high risk of death. Children up to 10 years old were also showing elevated rates of malnutrition.

“There is a high level of malnutrition. We are extremely concerned,” said Monica Rull, head of MSF projects in Kenya and Somalia.

Because of these worrying results, MSF is now including children older than five in their nutritional programs in Dagahaley camp.

Humanitarian aid too slow

MSF says that the ongoing delay in providing humanitarian aid is deeply problematic. The refugees must wait 40 days before being officially registered by the UNHCR and receiving a card entitling them to the regular food distributions. During those 40 days, they received intermittent food rations and a five-liter plastic container for water.

Since the beginning of July, newly arrived refugees have received food for at least receive food for 15 days, but it is not enough. “The World Food Program (WFP) must ensure more regular food distributions, and a nutritional survey for all the Dadaab camps needs to be carried out,” said Monica Rull. “Children up to 10 years old should also be included in order to confirm malnutrition rates in older children and thus adapt the nutritional programs.”

MSF is also calling for an accelerated registration procedure. Currently, there is only one registration center, in Ifo camp, for the entire Dadaab complex.

In areas on the outskirts of Dagahaley, MSF found that some refugees were receiving less than three liters of water per day – barely enough for one day’s drinking water in hot climates, but hardly enough for basic hygiene practices. The water supply must be increased. MSF teams have begun distributing more than 100 cubic meters (98 tons) of water by truck every day.

The MSF medical program is expanding

Pressure is mounting in the hospital run by MSF in Dagahaley camp, and in the five health posts MSF operates. More than 1,600 children with severe acute malnutrition are currently receiving  treatment in the ambulatory programs, and more than 700 new admissions are reported each week in the supplementary feeding programs.

treatment in the ambulatory programs, and more than 700 new admissions are reported each week in the supplementary feeding programs.

The staff has been registering an average of 107 new patient admissions to intensive nutritional care every week at the hospital. An extension with 60 additional beds for pediatric cases has been added to the facility, which was already operating beyond its capacity.

All actors working in the camp must scale up activities in order to provide appropriate assistance to the refugees, MSF believes. They must provide immediate assistance in the border areas. They must also find ways to relieve pressure in the camps while delivering the services urgently needed by the refugees who continue to arrive.

MSF activity in region

MSF teams are currently providing medical care to the 113,000 residents of Dagahaley camp, where an average of 500 additional people arrive every day. Some 25,000 people are living on the outskirts of the overcrowded site, and this figure is expected to keep growing. Beginning earlier this year, MSF teams have also been providing assistance to new arrivals on the outskirts of Ifo camp. Teams have been waiting for the planned extension, called Ifo 2, to open and enable the scale-up of activities.

MSF has been providing medical care in Kenya since 1992, and has worked in the camps at Dadaab for a total of 14 years. Since 2009, MSF has been the sole provider of medical services in Dagahaley camp, providing a 170-bed general hospital and five health posts to supply healthcare to the camp’s 113,000 residents.

Related articles: