US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (left) visited Azerbaijan during her trip to South Caucasus. Clinton emphasised the improvements achieved in her eyes by Azerbaijan whilst alluding to the significant room left for progress in the sphere of human rights. For instance, she highlighted the case of the two young bloggers, Adnan Hajizade and Emin Milli. However, in his latest report, Thomas Hammarberg, Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, presents a less optimistic picture of the situation in Azerbaijan, where freedom of opinion, freedom of association, the conduct of law enforcement officials, and the administration of justice are still issues of grave concern, as is the situation in the Autonomous Republic of Nakhchivan.

US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (left) visited Azerbaijan during her trip to South Caucasus. Clinton emphasised the improvements achieved in her eyes by Azerbaijan whilst alluding to the significant room left for progress in the sphere of human rights. For instance, she highlighted the case of the two young bloggers, Adnan Hajizade and Emin Milli. However, in his latest report, Thomas Hammarberg, Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, presents a less optimistic picture of the situation in Azerbaijan, where freedom of opinion, freedom of association, the conduct of law enforcement officials, and the administration of justice are still issues of grave concern, as is the situation in the Autonomous Republic of Nakhchivan.

Thomas Hammarberg’s comments are in line with the Concluding Observations issued in 2009 by the United Nations Committee against Torture (CAT) and the Human Rights Committee.

Moreover, in an appeal to the Parliamentary Assembly of Europe, Azerbaijani and international NGOs note in their common statement on human rights that in Azerbaijan “human rights violations continue to be numerous and widespread and occur on a systematic basis.” The predominance of torture and cruel inhuman and degrading treatment, and evidence that such policies permeate countless sectors of Azerbaijani society, epitomizes this conjecture and the complete disregard of international obligations. Hence torture and cruel inhuman or degrading treatment represented a key theme in the Hammerberg report, intertwined with limitations on other rights such as the right to freedom of expression and freedom of assembly.

Freedom of expression: Critical voices are subjected to harassment, and silenced

The HR Committee, CAT, the Parliamentary Assembly and the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, all state that journalists and human rights defenders are consistently subjected to harassment and beatings, and that this ill-treatment is rarely investigated.

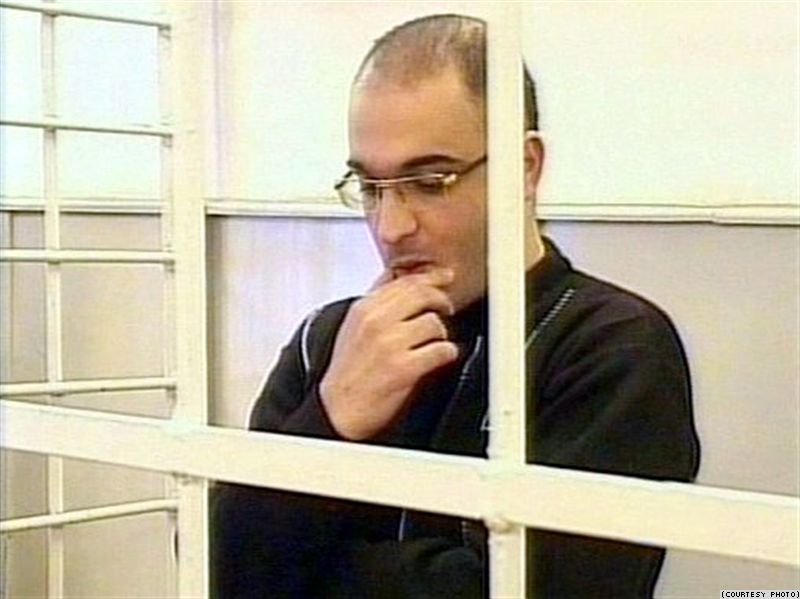

Commissioner Thomas Hammarberg draws special attention in his report to the frequent arbitrary imprisonment of journalists and the limitations this has on the right to freedom of expression. The ex editor-in-chief of several now defunct papers Eynulla Fatullayev (right), has been charged with an array of offences spanning from incitement of racial hatred and terrorism to tax evasion and most recently heroin smuggling whilst within prison. This charge has been denounced by Hammarberg as “highly improbable.” Article 19 also believe them to be fabricated and intended to keep Mr. Fatullayev incarcerated. Moreover, the earlier charges have been criticised owing to the absence of an independent tribunal. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe calls upon Azerbaijani authorities to release Eynulla Fatullayev as ordered by the European Court of Human Rights (resolution 1750 (2010)). Whilst international pressure has secured the release of a number of journalists, the Commissioner Hammarberg notes that “these releases do not appear to reflect a general trend or change of attitude of the authorities when dealing with persons expressing […] views considered as sensitive, incorrect, or offensive by the government” and Mr. Fatullayev remains incarcerated.

Commissioner Thomas Hammarberg draws special attention in his report to the frequent arbitrary imprisonment of journalists and the limitations this has on the right to freedom of expression. The ex editor-in-chief of several now defunct papers Eynulla Fatullayev (right), has been charged with an array of offences spanning from incitement of racial hatred and terrorism to tax evasion and most recently heroin smuggling whilst within prison. This charge has been denounced by Hammarberg as “highly improbable.” Article 19 also believe them to be fabricated and intended to keep Mr. Fatullayev incarcerated. Moreover, the earlier charges have been criticised owing to the absence of an independent tribunal. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe calls upon Azerbaijani authorities to release Eynulla Fatullayev as ordered by the European Court of Human Rights (resolution 1750 (2010)). Whilst international pressure has secured the release of a number of journalists, the Commissioner Hammarberg notes that “these releases do not appear to reflect a general trend or change of attitude of the authorities when dealing with persons expressing […] views considered as sensitive, incorrect, or offensive by the government” and Mr. Fatullayev remains incarcerated.

The Committee on Honouring of Obligations and Commitments by Members States of the Council of Europe condemned “the arrests, intimidation and harassment of journalists” (report, document 12270). Nevertheless, Azerbaijani authorities have denied that any criminal charges against journalists have been applied in connection with their reporting. At the HR Committee review, the delegation stated that “there had been no cases where journalists had been arrested on fabricated charges; if any journalist had been arrested it had been for specific criminal acts” (Summary record of the 2639th meeting, UN Doc.: CCPR/C/SR.2639).

Mr Fatullayev was originally convicted on defamation charges however Hammerberg deplauds such restrictions on the right to freedom of expression, and the “little progress towards [the] decriminalization of defamation.” This is represented by the continued initiation of lawsuits against journalists despite severe condemnation by the European Court of Human Rights, who found that such interference with the right to freedom of expression was disproportionate because criminal sanctions for defamation contravene the important role played by the press in democratic societies.

Crucially, despite all of the international criticism and outcry, on the 6 July 2010 Mr. Fatullayev was sentenced to another two and a half years in prison. This starkly reveals the complete lack of respect that Azerbaijan has for its international obligations and the absence of concern the Azerbaijani government has in terms of criticism from other states.

Freedom of assembly and association: permanent restrictions

As Azerbaijani and international NGOs emphasized in their common statement, since 2005 independent public gatherings have de facto been banned. Recent attempts in April, May, June and July 2010 to stage peaceful pickets were violently dispersed by police and unidentified plain-clothed authorities. Prior to 30 April 2010, when several youth activists were detained in Baku, police inspections were conducted at the Human Rights House in Baku and in the Media Rights Centre. Dozens of opposition party activists and several journalists were rounded up by police on 12 June , 19 June and 3 of July in peaceful unsanctioned rallies demanding that authorities respect freedom of assembly and improve the pre-election situation.

The Commissioner Hammerberg highlights that over the past two years, many civil society organizations, including religious groups, have been closed down, denied registration, evicted from their offices, and faced with inspections. The adoption of the amendments to the NGO law in June 2009 by the Parliament allows for increased government control over NGOs.

As underlined by the Commissionner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, recent legislative changes might limit even more the freedom of association in Azerbaijan: “The Commissioner cautioned against attempts to control activities of NGOs in an unduly strict manner.”

Torture: no concrete action by the government

Torture was only criminalized nationally in 2002 in Azerbaijan. Nevertheless the government has made limited attempts to align national legislation with international obligations, or even to align state practice with the national legislation. Principally the failure to reform the definition of torture has hindered the prohibition of this practice, as it is understood internationally. The Azerbaijani definition fails to specify the purpose of the act, this is fundamentally divergent from the internationally agreed-upon definition that emphasises special intent. Furthermore there is no reference to the position of the perpetrator, acts of torture committed “with the consent or acquiescence of a public official” are not differentiated, and hence public officials are only punished for direct involvement in acts of torture that they have instigated. CAT underscores the importance of bringing the definition of torture fully into conformity with the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment representing the crucial first-step in realizing real and complete prohibition.

Torture was only criminalized nationally in 2002 in Azerbaijan. Nevertheless the government has made limited attempts to align national legislation with international obligations, or even to align state practice with the national legislation. Principally the failure to reform the definition of torture has hindered the prohibition of this practice, as it is understood internationally. The Azerbaijani definition fails to specify the purpose of the act, this is fundamentally divergent from the internationally agreed-upon definition that emphasises special intent. Furthermore there is no reference to the position of the perpetrator, acts of torture committed “with the consent or acquiescence of a public official” are not differentiated, and hence public officials are only punished for direct involvement in acts of torture that they have instigated. CAT underscores the importance of bringing the definition of torture fully into conformity with the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment representing the crucial first-step in realizing real and complete prohibition.

CAT asserts the “widespread and routine use of torture or ill-treatment of detainees in police custody”, exacerbated by the admissibility of evidence obtained through such methods in Azerbaijani courts. Cases concerning alleged ill-treatment at police stations tend to be explained by resistance of the detained person to obey officers’ orders, whereas in penitentiaries they are justified by the disregard of the rules of discipline by inmates. In their common statement, NGOs write that “incidents are not investigated appropriately and law-enforcement officers suspected of being responsible for acts of torture are not prosecuted for ill-treatment, but instead [perhaps] charged with ‘minor, serious harm to health’.” This encourages state practice and a culture of impunity that accompanies the failure of justice. Hammerberg reaffirms these concerns, emphasizing the importance of “institutional and practical independence” of the mechanism for dealing with complaints against the police. Moreover, current state practice reflects a hierarchy between torture and the infliction of cruel inhuman and degrading treatment. This is inconsistent with the European Convention, which in this way differs from the CAT, considering each form of treatment to be equally significant.

Although the common statement welcomes the establishment of a public committee in Azerbaijan mandated to monitor penitentiary institutions, there remain significant limitations. The committee cannot make unannounced visits, neither is it granted access to pre-trial detention centres or the remand centre under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of National Security. The Committee against Torture recommended that this centre, in particular, either be closed or placed under the same jurisdiction as other detention facilities. However this recommendation has not been implemented and is particularly problematic because the accused are dependent upon the same authority, which conducts the pre-trial investigation for the provision of legal council.

Upcoming elections: imminent threats to human rights defenders

Gender rights, violence against women, denial of the rights of IDPs, denial of the right of conscientious objection, free elections, or independence of the judicial branch and lack of democracy and division of power are some of the problematic issues that could have been mentioned here as well. Thus exhibiting how difficult the situation is in reality in Azerbaijan, and in stark contrast to the idyll painted by the government for Hillary Clinton for her visit.

This situation is especially threatening in regard to the upcoming elections. The Azerbaijani and international NGOs expressed their concern “that the forthcoming elections will fail to meet international standards for free and fair elections. The Azerbaijani authorities have so far consistently refused to accept that in order to hold fair elections, there must be a level playing field for all political forces.”

Documents:

- HR Commissioner CoE report (2010)

- PACE report (2010)

- PACE resolution (2010)

- Concluding observations CAT (2009)

- Concluding Observations HR Committee (2009)

- Joint statement PACE (2010)

- HR Committee up-date (2010)

- “Why is Azerbaijan still a member of the Council of Europe?”, The Guardian blog of Afua Hirsch

- Press briefing of US Secretary of State Clinton and Azerbaijani Foreign Minister Mammadyarov

- HR Committee: the Government presents another face than reality

- Court slams Eynulla Fatullayev with another prison sentence

- Thomas Hammerberg unveils report regarding Azerbaijan

- PACE adopts resolution regarding Azerbaijan

- Verdict issued against the young bloggers

Further information:

Related articles:

HRHF’ support in international advocacy

Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF) is working to support Azerbaijani NGOs to strengthen its international advocacy effort.

Most recently, with the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (partner of the Human Rights House in Baku), the Norwegian Helsinki Committee (partner of the Human Rights House in Olso) and Article 19 (partner of the Open Word House of London), supported the lobbying effort towards the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). Delegates from those organisations had the occasion to brief members of PACE and with other Azerbaijani and international organiastions they wrote a joint statement to PACE (see document “Joint statement PACE 2010).

In 2009, HRHF supported the work of Azerbaijani members of the South Caucasus Network of Human Rights Defenders to participate in the review of Azerbaijan at the UN Committee against Torture and the Human Rights Committee. With the national partners, HRHF will work on the follow-up of these reviews. HRHF will also submit up-date information on Azerbaijan to the HR Committee at its 99th session (12-30 July 2010) (see document “HR Committee up-date 2010).