This story is adapted from an article originally published in Ukrainian by Educational Human Rights House Chernihiv.

Tropina is the Kherson regional coordinator for interaction with the public of the Ukrainian Parliament’s Commissioner for Human Rights. Fearful that her prominent position, where she would often make radio and TV appearances, would lead to her being recognised by the occupying Russian forces, Tropina would try to disguise her appearance when shopping for supplies or medicine to avoid detection.

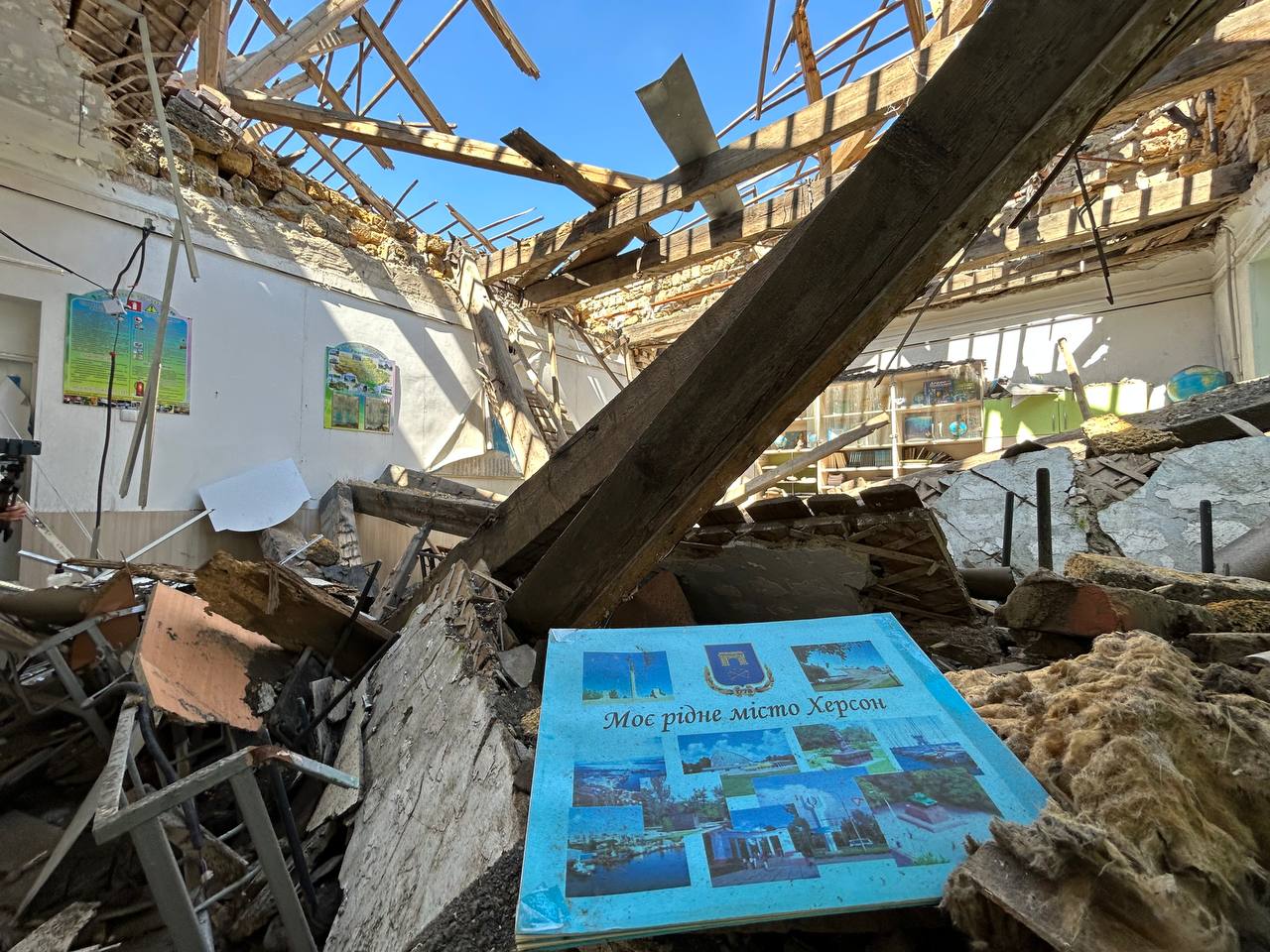

The city and suburbs were shelled over 100 times per day

“On February 23, 2022, everything went according to plan: we conducted a monitoring visit to the Oleshky Children’s Boarding Home [for children with disabilities, Kherson region]. Early in the morning on February 24, I saw the occupiers and military equipment from the window of my house. Our house is near a river, and there they were standing across from us on the other side.”

“It was unexpected. Nobody knew what to do. Police employees, the National Guard [of Ukraine], and the Security Service of Ukraine left the city…”

“I wasn’t going to leave Kherson — I spent the entire period of occupation in the city. But at some point, I realised it was impossible to continue living under constant shelling. The city and suburbs were shelled over 100 times per day. My friends encouraged me to leave. On November 11, 2022, Kherson was liberated, and on January 7, 2023, my family and I left.”

Tropina shares that the responsibility for her family finally convinced her to leave Kherson. Tropina is the primary caregiver for her disabled husband, and her mother was evacuated from her village in the Kherson region. Tropina’s father died following the full-scale invasion after battling illness, she says that the invasion was the final straw for him.

Living and caring for ill family members under occupation

Tropina says that getting vital medication for her husband and mother was the most challenging thing during the occupation.

“During the occupation, only a few pharmacists worked in the city, all of them private. On social media and in person, people shared information about the delivery status of medications to pharmacies. The queues were enormous. And even if you stood in line, there was no guarantee that you would get the needed medication.”

“An owner of one pharmacy lived not far from me. When they ran out of medications, the owner would ask her husband to get medicines from the unoccupied [Ukraine-controlled] territory, where he had to travel through Zaporizhzhia. They managed to bring a carload of medicines three times this way. “

“Later, in September, a ban on private pharmacies was issued – state policy in the Russian Federation where only state pharmacies have the right to work. Therefore, it became more difficult to buy any medications. In fact, they were in the city, being sold [by non-pharmacists] directly in the [open air] market on folding tables, [sellers – non-pharmacists] did not follow the storage conditions, especially considering the southern summer heat. In addition, the sellers were not pharmacists, sometimes it was impossible to see the expiration date on the package, and they were too expensive.”

According to Tropina, there were no significant problems with the availability of food, the main issue was lack of money. Some people received money through bank transfers from relatives, while others looked for part-time work.

“Back in March-April last year, many people stayed in Kherson. But already at that moment, there was a massive problem with employment, and it was impossible to withdraw cash. In addition, the occupiers did not allow us to use bank terminals [while shopping].”

“We knew there were a couple of shops in Kherson where you could still pay by card. We came, stood quietly, and watched to see if there were any Russians or strangers [present], who could be collaborators, blinked [an indication between seller and customer that a terminal transaction can be done] and paid quietly. We just gave cards with pin codes to the seller under the counter, and they returned them back in bags with groceries. This is how people took care of each other and helped each other. We are grateful to them for this kindness.”

Tropina was afraid to live in the city not only because of shelling but also because of the fear of being recognised. Before the start of the full-scale Russian invasion, she was often invited to the local radio and television.

“I would walk down the street in old shabby clothes, and styled my hair differently so that no one would recognise me.”

“They [men in military uniforms] also came to our house, but not because of my job. They went to each house and inspected the citizens. When the occupiers settled, they brought Russians into those houses and apartments where no one lived. They simply issued ‘housing warrants’, with which mainly teachers and doctors from Russia were moved in. Even pregnant women came.”

Work and assisting people under occupation

According to Tropina, until the beginning of March, two representatives of the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights worked in Kherson, and she worked as a coordinator.

“One of my colleagues quit right away, and one stayed. Before the full-scale invasion, new computers and furniture were delivered to our office. And my colleague decided to go and check the situation at the office and was caught for a ‘conversation’. They talked to him for a long time and attempted to coerce his cooperation. He was unswayed and rightly refused the invaders. Now he lives on the left side [of the Dnipro river in Kherson region], where his relatives live, but unfortunately, it is still under occupation.”

Before the invasion, Tropina and her colleagues monitored the human rights situation in places of detention (including, for example, penal institutions, specialised schools for children, care homes for the elderly, etc). When the war started, staff of these facilities began to call her and her colleagues to ask what to do. She continued to try and help people wherever possible.

“Once, we got a call from a [care home for men with disabilities] and were told they only had food left for a few weeks. There were over 100 men at the care home. They ate from leftover supplies: condensed milk in tins, flour and yeast. It saved many of them at the beginning [of the occupation]. There was a similar story for a [care home for women with disabilities] with about 300 women. They looked for food in warehouses and stores so that people could survive.”

In October 2022, it was reported that 54 women from Kherson psychoneurological boarding school were transferred by Russia-controlled authorities for a so-called “vacation in Crimea” without further contact.

“The head of a correctional colony in Kherson called me. They had to find a way to feed the inmates. He said that he was told by someone at the central level [Ministry of Justice of Ukraine] to open the gate and let the prisoners look for food themselves. He decided not to release the prisoners because around 1000 of them were repeat offenders and therefore decided to ‘change the flag’ [accept de-facto Russian administration]. Given the circumstances, it is difficult to judge his decision. But later we discovered that the occupation authorities took these people to the territory of Russia. Relatives called us and said that the prisoners were forced to take up arms and fight against Ukraine.”

Another difficulty, according to Tropina, was related to the transfer of medicines to the Russia-occupied left bank of the Dnipro River in the Kherson region.

“In every district, there are children, for example, with psychiatric disorders who need help. They need medical treatment.”

“The chief doctor of the Kherson Regional Institution for the Provision of Psychiatric Care agreed to help. Without hesitation, he drove his motorcycle to bring all the medications he had in stock to the occupied Left bank [of the Dnipro River in the Kherson region, Summer 2022]. Imagine how he went through checkpoints, risking his life. That same evening, he called me and said that he had delivered the medications and there should be enough until September [2022].”

Tropina says that the human rights situation in the occupied part of the Kherson region is very difficult.

“Especially for people who need help — people with HIV, alcohol and drug addicts, palliative patients. The occupying authorities do not help them in any way. People’s medical documents were taken to Henichesk district [about 200 km from Kherson], where they [Russian de-facto authorities] now have a so-called ‘support hospital’. And in order to get some help, people are forced to spend large amounts of money to get there.”

“We need to take care of people who can be helped or provide [end of life care]. Now, it is very difficult to work with such cases because of the occupation.”

And we also need to take into consideration constant shelling and, as a result, poor phone connection in the city. In addition, Kherson is removed from the list of cities that are considered to be in the war zone. And although there are no battles in Kherson itself, the city, the entire coastal zone and the suburbs are under constant shelling.

Educational Human Rights House in Chernihiv provided emergency support for Tropina and her family with evacuation and relocation including support for essentials including food, temporary accommodation, medication, etc.

This support was provided under the framework of Emergency Support Ukraine (ESU) – a regional project that provides opportunities for emergency support for Ukrainian civil society and independent media in the wake of the full-scale Russian invasion. ESU is funded by the European Union and implemented by ERIM-led coalition of partners, including Human Rights House Foundation.

After relocating to the neighbouring region, Tropina continued her human rights and volunteer activities. She is currently with the Charitable Foundation «Stabilization Support Services» as a head of their regional project supporting internally displaced persons, she documents human rights violations concerning people with HIV, hepatitis and tuberculosis and volunteers at the probation facilities and the Secondary legal advice service.

Tropina plans to return to Kherson in the future, to live and work there.