The draft of the amendment was filed to the lower house of the Polish Parliament – Sejm in September 2008. It proposed the change of the Article 256 of the Penal Code (concerning the prohibition on inciting hatred on the grounds of nationality, ethnicity, religion or non-religion, as well as propagating fascism or another totalitarian regime) by adding three new clauses.

The draft law came into force on 8 June 2010. From now on, the Criminal Code prohibits also the production, conservation, import, acquisition, storage, possession and presentation with the intent to distribute items of an above mentioned content. As a result of this amendment, not only the symbols of totalitarian regimes, but also other that incite hatred based on the above – mentioned criteria are prohibited. The whole idea of extending the range of forbidden activities turned out to be very controversial and started the discussion in the Polish mass media concerning the necessity and scope of the regulations.

The Arguments of the Both Sides

The authors of the draft amendment indicated in its justification that in its former version the Article 256 of the Penal Code classified distribution merely as an act of public performance, and did not acknowledge the use of the Internet as a mean of the incitement to support totalitarian ideologies. According to the authors of the project, the prepared amendment was to remove a significant loophole in the law. Moreover, the justification states that such a regulation fulfills the expectations of the Polish society where “the memory of the war, as well as the crimes of fascism and communism, is still vivid”. In addition, advocates of the regulation indicated the fact that the production of materials related to the promotion of totalitarian systems is on the rise in Poland. In their view, such a practice has a harmful impact on a society and leads to the rebirth of a fascination with the leaders of totalitarian regimes and the ideologies that governed them.

On the other hand, the opponents of the above mentioned amendment stated that any changes in the penal law shall be motivated either by a change in a criminal policy or by the findings of an analysis of the pre-existing structure of the penal law and its inability to fulfill the aims of a criminal policy. Thus, if a change in a criminal policy does not occur and the regulations in their previous version, though rarely used, were, however, used appropriately, any changes in this range are necessary. Regarding the claim of fulfilling the expectations of the Polish society (in relation to remembrance of the crimes of fascism), it would be worth quoting a thesis of the judgment of the European Court of Human Rights in the case of Vajnai v. Hungary “ A legal system which applies restrictions on human rights in order to satisfy the dictates of public feeling – real or imaginary – cannot be regarded as meeting the pressing social needs recognised in a democratic society, since that society must remain reasonable in its judgement. To hold otherwise would mean that freedom of speech and opinion is subjected to the heckler’s veto.”

Moreover, during the discussion on this subject, there were presented some arguments stating that a prohibition of the production or distribution of items depicting symbols associated with fascist or other totalitarian systems is definitely a too far-ranging restriction. Furthermore, representants of this doctrine indicated that the necessity of amending the Article 256 was dubious. “The courts sometimes decide in a shocking manner, for example, in case of the so-called “Roman salute” and paramilitary parades. However, it proves that the judges tend to decide unwisely rather than the law is imperfect”.

The Amended Article 256 of the Criminal Code and the Constitution

In April 2010, the Members of the “Lewica” Parliamentary Club submitted a motion to the Constitutional Tribunal. They asked the Tribunal whether the amended article is in the conformity with the Polish Constitution. In the motion, the MPs hold that the newly-introduced regulation is not consistent with the fundamental principle of the penal law – nullum crimen sine lege certa . According to the applicants, the legislators used imprecise terms which may cause certain problems while defining their range. In the applicant’s view “the direct effect of the introduction of the Article 256 §2 – 4 of the Penal Code into the body of laws could be the unrestricted interpretation of the penal law and, in effect, punishment for activities and deeds posing little social harm”.

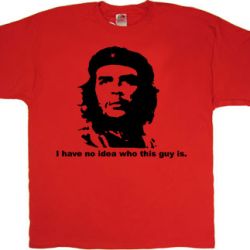

At this point, it would also be worth noting one additional aspect of the newly-introduced amendment. Currently, the crime specified in Clause 2 of the Article 256 of the Penal Code is conditional in its nature: “he or she who, with the intent to distribute…”. It means that not every case of possession or production of an object that depicts the symbols of totalitarian regimes shall be punished. However, in the debate concerning the above mentioned amendment, it was very often stated that even the possession of e.g. Che Guevara T-shirt represents a too far-reaching interference in the liberty of the individual. This fallacious assumption is reflected in the thesis presented by the group of MP’s who stated that “the casuistic formulation of the characteristics of the crime renders the decried regulation hardly intelligible, especially because it does not indicate a conditional intent- an objective of its operation”.

Can Che Stay?

Not every act of the presentation or distribution of totalitarian symbols will be found a crime in the view of the amended Article 256. In Clause 3 of the amendment of the Article the legislators anticipated the possibility of four exceptions when people shall not be punished for such actions (“a crime is not committed by a perpetrator of a forbidden act specified in Clause 2, if he or she commits the said act in the course of artistic, educational, collectible or scientific activity”).

However, none of those activities is legally defined on the grounds of the penal law. Thus, the process of determining their scope will be dependent on the circumstances of a given case and the discretion of the court. Such a situation may cause several threats to the liberty of the individuals. It is not always possible to unequivocally answer the question concerning the point where artistic activity or the freedom of expression ends, and the “base” dissemination of fascism and communism begins.

The propagation of totalitarian regimes is one of several aspects of the phenomenon of the hate speech. Statements, shouts at football stadiums during matches, and messages spray painted on walls that incite hatred based on, for instance, ethnic background, race or religious beliefs are proofs of the continuous presence of this problem in the society. Therefore, the intention of the legislators, who introduced such a wide ranging criminality of acts related to the propagation of totalitarian regimes, and at the same time did not conduct any investigation concerning the necessity of the expansion of the criteria of the incitement to hatred present in the Article 256 of the Penal Code, remains unclear. It is worth mentioning that the Campaign Against Homophobia presented a draft of an amendment of the Article 256, according to which the incitement of hatred based on, inter alia, sexual orientation would be punishable.

It seems that the controversies concerning the amended Article 256 of the Criminal Code will not subside along with its enactment, while the concerns regarding its use will return following the first court resolutions based on this regulation. It would also be prudent to wait for the resolution of the Constitutional Tribunal regarding the conformity of this Article with the Constitution. Until then, the question “What about Che?” remains unanswered.

* Małgorzata Szuleka – Lawyer at the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights