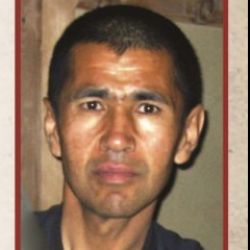

According to the said article [1] Mr Mussa is a disabled person. He lost his leg in a land mine explosion while serving in the army. For sixteen years before his arrest Sayed Mussa worked for the International Committee of the Red Cross. Nine years ago he was baptised into the Christian faith and thereby converted from Islam, the official Afghan religion which he used to practise. Afghan authorities arrested him for converting to Christianity nine months ago.

The NY Times article emphasises that state bodies in Afghanistan do not comply with the principle of religious freedom guaranteed under the Afghan Constitution of 2004. The reason for that is the lack of a clearly defined relationship between constitutional norms and religious standards. Consequently, Afghan courts, while adjudicating on individual cases, are free to rely either on domestic state law or on Shariah, the Islamic law. Under some interpretations of Shariah, which may be used in arguing the case before state courts, leaving Islam is considered apostasy, a capital offence.

The New York Times sources reported that Sayed Mussa had been repeatedly denied any contacts with his family. He was ill-treated and physically abused both by prison guards and the other inmates. Mr Mussa has not been put on trial. Currently, Sayed Mussa is detained in the Kabul detention centre, where he was transferred after the US authorities intervened on his behalf.

From the description of the case provided in the article it follows straightforwardly that Mr Mussa’s right to a fair trial and, in particular, his right to defend himself, have been violated. As stressed in the quoted article it cannot be said for sure whether Sayed Mussa has an attorney to represent him. Despite the fact that two defence lawyers has been so far involved in his case, currently he has no contact with any of them. The article reports that the court barred the first lawyer from representing Mr Mussa without informing the detainee of its decision. It is also indicated that a justified fear of reprisals from the Afghan authorities for representing a client in an apostasy case may affect the quality of services rendered by any lawyers who would consider representing Mr Mussa.

According to The NY Times and other media reports Sayed Mussa is a victim of serious human rights violations, including the infringement of religious freedom and the right to a fair trial and defence. More importantly, he is facing a death sentence which may be carried out with the full sanction of the Afghan law. Then, the case does not concern actions of private organisations or independent religious or guerilla groups but formal institutional measures of the Afghan state apparatus.

The Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights pointed out that this case exemplifies the violation of values which are enshrined in the Polish constitution. In opinion of the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights Polish involvement in international missions and their objectives ought to be perceived against a backdrop of these values.

The Republic of Poland maintains relations and cooperates with the Afghan state that controls the country’s public institutions. Bilateral Polish-Afghan relations go back to 1927, but it was only after collapse of Taliban regime that more active political contacts between Polish and Afghan authorities started to develop. Specifically, let us remind you that in 2006 Poland decided to sent its military forces to Afghanistan as part of the NATO’s operation. Poland also actively supports reforms in Afghanistan aiming at upholding democratic rules and human rights. Further, it can be read in the relevant documents of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that “priorities of Polish foreign aid are, among other things, a cooperation for development and involvement in international cooperation for democracy and advancement of civic society “[2].

The Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights emphasized that the way in which Afghan authorities treat Sayed Mussa, as depicted in The New York Times’ article, constitutes a breach of international obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, whose parties are both Afghanistan and Poland.

The Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights appealed to take appropriate diplomatic steps designed to secure Sayed Mussa’s release.

[1] The article “Afghan Rights Fall Short for Christian Converts”, The New York Times, 5th February 2011 is available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/06/world/asia/06mussa.html?_r=1, a copy of article is attached hereto.

[2] Cf. an announcement of the Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs of 20 June 2006 regarding the launch of a call for proposals for tasks within the scope of Polish foreign assistance and international development co-operation available at: http://www.msz.gov.pl/Otwarty,konkurs,na,zadania,z,zakresu,polskiej,pomocy,zagranicznej,i,miedzynarodowej,wspolpracy,rozwojowej,6494.html