Such radical changes in fortune are the norm to the woman described as the "Saharawi Gandhi" for her non-violent protests.

On November 14, Morocco refused to allow Haidar to return to her home in the Western Sahara. She had been in New York to receive the Civil Courage Prize for her work in support of human rights for her homeland.

Return "dead or alive"

Although she had neither a Moroccan nor Spanish passport, she was allowed to return to Lanzarote with the government in Madrid guaranteeing her safe conduct, although she was later fined on public order offences.

The Spanish government offered her a passport but, insisting on keeping her Western Saharan status, Haidar refused the gesture.

Instead she vowed to return to her native land "dead or alive."

Haidar had upset Morocco because she rejected that country’s right to rule over the Western Sahara.

The prime minister of the self-proclaimed Republica Arabe Saharaui Democratica (RASD), Abdelkader Taleb Oumar, called on the international community to pressure Morocco to comply with international law and appealed to the Spanish monarch King Juan Carlos to add his support by interceding with the Moroccan king on Haidar’s behalf.

Diplomatic priority

On December 14, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton met the Spanish Foreign Minister Miguel Angel Moratinos at the White House with Haidar at the top of their agenda.

The meeting had originally been scheduled to discuss Spain taking over the presidency of the EU on January 1 but as Haidar’s condition weakened it became a diplomatic priority to seek a solution. From the US capital, Moratinos issued a plea to Haidar to end her hunger

The meeting had originally been scheduled to discuss Spain taking over the presidency of the EU on January 1 but as Haidar’s condition weakened it became a diplomatic priority to seek a solution. From the US capital, Moratinos issued a plea to Haidar to end her hunger

strike.

Morocco stood fast over Haidar. The foreign minister Taieb Fassi Fihri insisted that his government would make no concessions. He accused the activist of blackmail and said it was a campaign organised by Algeria and the Polisario Front.

Hanging by a thread

Apart from demanding that Haidar be allowed to return to the Western Sahara in dignity, Oumar had also called for the release of all Saharan political prisoners, an investigation into the fate of those who have disappeared and the opening of the area to international human

rights observers.

But on December 17, there was frantic activity as Haidar was admitted to Lanzarote hospital suffering from abdominal pain as a result of her 32-day hunger strike. Following reports that her life was hanging by a thread, there were increased diplomatic contacts between the Spanish and Moroccan governments, with the latter finally relenting

and allowing her to return home.

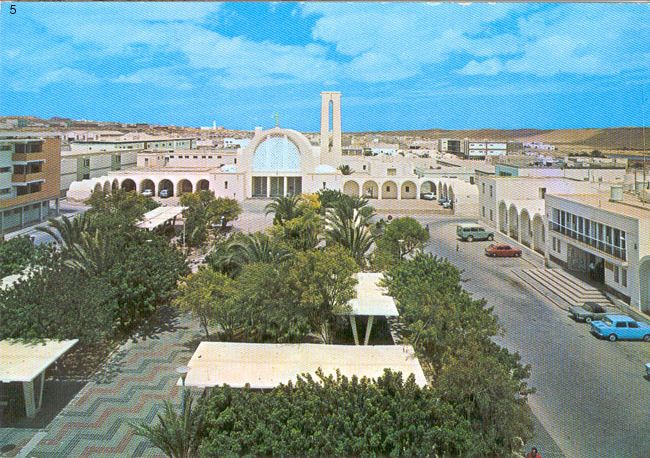

She was declared free to leave Spain for her home country to be with her children and mother. At midnight on the same day she was flown in a hospital plane to the capital of the Western Sahara, El Aaiun (left). She was accompanied on her journey by her sister and the doctor who had been attending to her.

She was declared free to leave Spain for her home country to be with her children and mother. At midnight on the same day she was flown in a hospital plane to the capital of the Western Sahara, El Aaiun (left). She was accompanied on her journey by her sister and the doctor who had been attending to her.

On receiving the news that she was free to go home, her protest and hunger strike ended. On leaving Spain Haidar declared: "This is a triumph – a victory for international law, human rights and the Saharan cause."

But the victory came at a price

Haidar now says she has been held under house arrest since her return home to El Aaiun on December 18. Before Christmas, the Moroccan security forces prevented a Reuter’s reporter from visiting Haidar at her home, so she gave a telephone interview with the press agency’s office in Rabat on Christmas Eve.

Haidar said: "My isolation continues. I am under house arrest. The members of my family and friends have problems visiting me. The shops in my quarter are suffering from the isolation."

She continued: "I have the value of my convictions to continue with the cause of self-determination for the Saharan people. Nothing will make me give up – the threat of jail, kidnapping, torture or exile."

She accused Morocco of using "carrot and the stick" politics with the Polisario Front and the Saharans, adding that "Morocco is repressing the Saharan population whilst it is negotiation with the Polisario Front."

Western Sahara: A tragic history Like many of the troubled lands in today’s world, the tragedy of Western Sahara lies in its colonial rule by Spain and Francisco Franco’s desire to rid his country of its obligations "muy pronto."

Like many of the troubled lands in today’s world, the tragedy of Western Sahara lies in its colonial rule by Spain and Francisco Franco’s desire to rid his country of its obligations "muy pronto."

Indeed, it was literally Franco’s dying act that his government secretly signed a tripartite agreement with Morocco and Mauritania allowing Spain to abandon the Western Sahara. The agreement was signed on November 14 1975 – days later, Franco was dead.

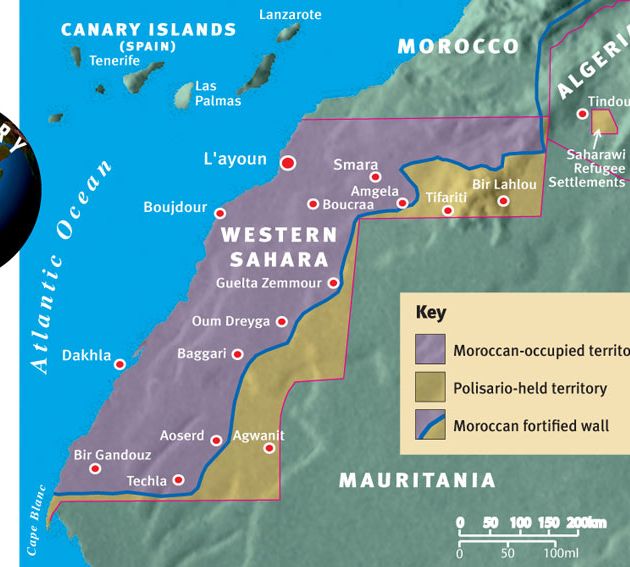

Spain was gone from the Western Sahara within three months. Instead of the tripartite administration envisaged in the accord, Morocco and Mauritania each annexed parts of the territory. Morocco seized the northern two-thirds, creating its southern provinces, while Mauritania

took the southern third as Tiris al-Gharbiyya.

Franco’s Spain may have abandoned its former colony, but the Polisario Front, backed by Algeria, forced Mauritania to withdraw in 1979. This solved little as Morocco merely moved in to the territory that Mauritania had controlled, setting up the sand wall in the desert to contain the Polisario liberation fighters.

In 1991, the fighting ceased after the UN brokered a peace agreement. However, this still leaves the former colony that covers some 266,000 square kilometres of desert flatlands – one of the most sparsely populated nations on Earth – in a state of limbo.

Would-be nation

El Aaiun, where Haidar is now under house arrest, is the Western Saharan capital – home to over half of the more than 500,000 people who live in the former Spanish colony.

Morocco and the Polisario Front independence movement with its Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic government are vying for control of these desert sands.

It will come as no surprise that the US has sat on the fence while the SADR has won the backing from 46 states plus the African Union, and Morocco has the support of the Arab League.

Spain is one of those countries refusing to recognise Morocco’s sovereignty claim.

This support swings with the fickleness of international trends and it is left to brave people such as Haidar and her Collective of Sahrawi Human Rights Defenders to keep the plight of this impoverished would-be nation in the hearts and minds of those who believe in civil rights and the right to self-determination for all.