Prior to the protests a lot was said about the importance of the internet as a “free space”, where opposition discourse was thriving, especially in the context of its limited manifestation in the offline world.

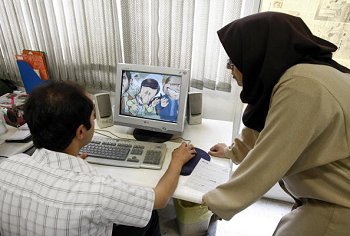

The Persian blogosphere was hailed as one of the most vibrant non-English speaking communities where youth, women, homosexuals, and religious and ethnic minorities were expressing and to some extent mobilising themselves.

The Persian blogosphere was hailed as one of the most vibrant non-English speaking communities where youth, women, homosexuals, and religious and ethnic minorities were expressing and to some extent mobilising themselves.

Internet as “fourth estate”

Occasionally, the internet also played a “fourth estate” role — that is, the ability to create an independent institution making the authorities accountable for their actions. There were a number of secretly recorded amateur videos documenting the wrongdoing of some Iranian officials — the subsequent wide coverage of those videos made it very hard for the Iranian officials to deny the incidents.

These two political functions of the internet — a “free space” and a “fourth estate”, also played important roles in the aftermath of the election. The internet became the backbone of the green movement, as severe restrictions were imposed on the movement’s offline activities. Citizens used their mobile phones and became the eyes and ears of the international media whose correspondents had been expelled from Iran.

The videos documented the participat ion of Iranians in street protests and the brutality of force used against them by the authorities, resulting in the widespread practice of adding the postfix “revolution” to social media platforms like Twitter and YouTube.

ion of Iranians in street protests and the brutality of force used against them by the authorities, resulting in the widespread practice of adding the postfix “revolution” to social media platforms like Twitter and YouTube.

Authorities wage war against internet freedom

However, the green movement was not simply allowed to use the internet for its own end. The Iranian authorities tried to stop the “Twitter revolution” by waging an active war against internet freedom.

The authorities went beyond simple internet content filtering by tampering with internet connections and mobile phone services, by jamming satellite broadcasting, and by hacking and attacking opposition websites.

They also monitored online dissenters and used the information obtained to intimidate and arrest them. They threatened service providers in Iran to remove ‘offensive’ posts or blogs and more significantly, they tried to fill the information void created by these measures with misinformation.

There has been a sense of disappointment amongst the supporters of the Twitter revolution. We should try to make sense of its shortcomings.

Social and conventional media need each other

It became clear that social media (staffed by citizen journalists) and conventional media needed each other to function. Given the  government’s severe restrictions on access to the internet and its infiltration of the social media’s platforms with fake content, its audience was limited. Citizen journalists relied on conventional media to take the best of their content and reach a larger audience, while the latter needed the former to continue their news cycles in the absence of correspondents on the ground.

government’s severe restrictions on access to the internet and its infiltration of the social media’s platforms with fake content, its audience was limited. Citizen journalists relied on conventional media to take the best of their content and reach a larger audience, while the latter needed the former to continue their news cycles in the absence of correspondents on the ground.

Twitter and Facebook: Bridging rather than mobilising

Facebook and Twitter were more influential in mobilising diaspora Iranians showing solidarity rather than mobilising street protests inside Iran. Owing to their knowledge of context and language, diaspora Iranians were also able to connect the outside (mainly the media) to the inside. Both the platforms were filtered before the election and remained inaccessible in Iran during the protests.

Do not underestimate the basics

In the days after the disputed election, the Iranian authorities shut down many of the news websites set up by supporters of Mousavi and Karoubi and other opposition groups by arresting the technical teams involved in their maintenance, initiating intense Denial of Service (DOS) attacks and hacking.

The opposition clearly took having access to secure hosting and capable technical support for granted and did not expect these incidents to occur. Its lack of preparation meant that many of them struggled to get back online and to remain online in the following months.

Knowing how to operate safely online is important

There have also been a number of reports that activists were presented with copies of emails exchanged with other activists during their interrogation and were arrested for their online activities. Many of them were also asked to provide the credentials of their Facebook accounts and were questioned extensively on their relationships with friends on their list.

The Iranian authorities used this fear for further power projection by claiming that the Iranian Police has access to all the emails and SMS messages exchanged in Iran and can monitor them. All of these tactics have created fear and self-censorship among the ordinary internet users and activists in Iran, a fear that is perpetuated by a lack of knowledge of the very basics of information security.

There will be more limitations on the internet

The Iranian authorities used to consider the development of the internet in Iran as an enabler for economic development. During the Rafsanjani and Khatami presidency, the government invested heavily in expanding the internet infrastructure, resulting in a high growth rate of internet users.

However, this has now changed and Ahmadinejad’s government has allocated 500m US dollars in this year’s annual budget (2010-11) to “counter the soft war”. This effectively means imposing more restrictions on opposition movement’s use of the internet. The fifth economic plan devised by his government does not have any indicators for increasing the internet penetration rate in Iran, contrary to the past two economic development plans.

This indicates that the Iranian government is not interested in increasing the number of internet users in Iran, at least not for the next five years .

.

The internets reach is limited

Internet users in Iran are predominantly middle and upper middle class and internet access remains limited among the less affluent sections of Iranian society. Mousavi has stated numerous times that the Green Movement should try to reach out to the working class and bring it on board.

But the internet is the only available media option

The internet is the only media space that is available to the green movement as other forms of media are heavily controlled by the government and it is not possible to launch a newspaper, radio or TV station inside Iran. Satellite broadcasting of political TV stations based outside Iran will be subjected to heavy jamming. The short wave radio broadcasted from outside is also losing its audience significantly, as highlighted in a recent audience survey by the BBC World Service.

The green movement should think “small media”

The green movement and its supporters inside and outside Iran need to go beyond the common perception and prescribed use of the internet (like YouTube, Twitter and Facebook) and come up with new and innovative solutions.

Mousavi himself has encouraged the green mo vement to embrace “small media”, which relies on offline social networks for further distribution of information. He is reminding the Green Movement of the lessons learned from the 1979 and Constitution Revolutions as both used small media to mobilise support and achieve their aims.

vement to embrace “small media”, which relies on offline social networks for further distribution of information. He is reminding the Green Movement of the lessons learned from the 1979 and Constitution Revolutions as both used small media to mobilise support and achieve their aims.

Small media has four main characteristics:

– It is distributed and is therefore not prone to blockage

– It produces sharable information products

– It relies on highly resourced and networked individuals to reproduce sharable information products

– It uses the social networks of highly resourced individuals to distributed sharable products to less resourceful individuals

Leaflets and cassette tapes were widely used in 1979 revolutions. These days the digital equivalents of them will be CDs, DVDs, memory sticks, email, Bluetooth on mobile phones, peer to peer file sharing etc. The green movement only has the internet but it has to change its approach towards it by going beyond its widely prescribed uses.

It is time to replace the Twitter revolution with small media discourse.

HRH London, based on the article by Mahmood Enayat, published by Index on Censorship. See the original article here. Mahmood Enayat is a doctoral student at the Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford. He is also the Director of Iran at the BBC World Service Trust, where he is responsible for managing the Iran media development project.