As the Internet, modern cell phones and other new digital tools provide a possibility to people become journalists and spread free speech easily, authoritarian countries try to prevent free blogging, video sharing, text messaging, and live-streaming.

10 tools

This month Human Rights House (HRH) pays much attention to the new modern possibilities letting to avoid state borders and express free speech. HRH also focuses on new barriers and attempts to suppress free flow of information.

Find here an article about a study on political censorship of internet. Here is the other text about new technologies and possibilities they provide.

This time we present a special report by CPJ which gives more details on suppression of internet freedom. CPJ examines the 10 prevailing tactics of online oppression worldwide and the countries that have taken the lead in their use.

The technology used to report the news has been matched in many ways by the tools used to suppress information. Many of the oppressors’ tactics show an increasing sophistication, from the state-supported email in China designed to take over journalists’ personal computers, to the carefully timed cyber-attacks on news websites in Belarus. Still other tools in the oppressor’s kit are as old as the press itself, including imprisonment of online writers in Syria, and the use of violence against bloggers in Russia.

Here are the 10 prevalent tools for online oppression:

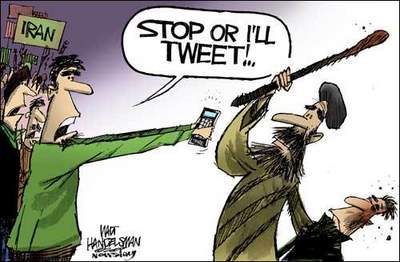

Web blocking: Iran

Many countries censor online news sources, using domestic Internet service providers and international Internet gateways to enforce website blacklists and to block citizens from using certain keywords.

Since the disputed 2009 presidential election, however, Iran has dramatically increased the sophistication of its Web blocking, as well as its efforts to destroy tools that allow journalists to access or host online content.

to access or host online content.

In January 2011, the designers of Tor, a privacy and censorship circumvention tool, detected that the country’s censors were using new, highly advanced techniques to identify and disable anti-censorship software. In October, blogger Hossein Ronaghi Maleki was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment for allegedly developing such anti-filtering software and hosting other Iranian bloggers.

The government’s treatment of reporters has been among the worst in the world; Iran and China topped CPJ’s 2010 list of worst jailers of the press, with 34 imprisoned apiece. But by investing in new technology to block the Net and actively persecuting those who circumvent such restrictions, Iran has raised the bar worldwide.

Precision censorship: Belarus

Permanent filtering of popular websites often encourages users to find ways around the censor. As a result, many repressive regimes attack websites only at strategically vital moments. In Belarus, the online opposition outlet Charter 97 predicted that its site would be disabled during the December presidential election. Indeed it was: On Election Day, the site was taken down by a denial-of-service, or DOS, attack.

Indeed it was: On Election Day, the site was taken down by a denial-of-service, or DOS, attack.

A DOS attack prevents a website from functioning normally by overloading its host server with external communications requests. According to local reports, users of the Belarusian national ISP attempting to visit Charter 97 were separately redirected to a fake site created by an unknown party.

The election, conducted without the scrutiny of critical outlets like Charter 97, was marred by secretive vote-counting practices, international observers said.

Technological measures were not the only attacks on Charter 97: The site’s offices were raided on the eve of the election, and editors were beaten, arrested, and threatened. In September 2010, the site’s founder, Aleh Byabenin (above), was found hanged under suspicious circumstances.

Denial of access: Cuba

High-tech attacks against Internet journalists aren’t needed if access barely exists. In Cuba, government policies have left domestic Internet infrastructure severely res tricted. Only a small fraction of the population is permitted to use the Internet at home, with the vast majority required to use state-controlled access points with identity checks, heavy surveillance, and restrictions on access to non-Cuban sites.

tricted. Only a small fraction of the population is permitted to use the Internet at home, with the vast majority required to use state-controlled access points with identity checks, heavy surveillance, and restrictions on access to non-Cuban sites.

To post or read independent news, online journalists go to cybercafes and use official Internet accounts that are traded on the black market. Those who do get around the many obstacles face other problems. Prominent bloggers such as Yoani Sánchez have been smeared in a medium accessible by all Cubans: state-run television.

Cuba and Venezuela recently announced the start of a new fiber-optic cable connection between the two countries that promises to increase Cuba’s international connectivity. But it’s unclear whether the general public will benefit from connectivity improvements any time soon.

Infrastructure control: Ethiopia

Telecommunications systems in many countries are closely tied to the government, providing a powerful way to control new media. In Ethiopia, a state-owned telecommunication s company has monopoly control over Internet access and fixed and mobile phone lines.

s company has monopoly control over Internet access and fixed and mobile phone lines.

Despite a management and rebranding deal with France Telecom in 2010, the government still owns and directs Ethio Telecom, allowing it to censor when and where it sees fit.

OpenNet Initiative, a global academic project that monitors filtering and surveillance, says Ethiopia conducts “substantial” filtering of political news. This matches Ethiopia’s continuing crackdown on offline journalists, four of whom are imprisoned for their work, according to CPJ records.

Ethiopian government control does not simply extend to phone lines and Internet access. The country has also invested in extensive satellite-jamming technology to prevent citizens from receiving news from foreign sources such as the Amharic-language services of the U.S. government-funded Voice of America and the German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle.

Attacks on exile-run sites: Burma

For journalists who have been run out of their own country, the Internet is a lifeline that enables them to continue reporting news and commentary about their  homeland. But exile-run news sites still face censorship and obstruction, much of it perpetrated by home governments or their surrogates. Exile-run sites that cover news in Burma face regular denial-of-service attacks.

homeland. But exile-run news sites still face censorship and obstruction, much of it perpetrated by home governments or their surrogates. Exile-run sites that cover news in Burma face regular denial-of-service attacks.

The Thailand-based news outlet Irrawaddy, the India-based Mizzima news agency, and Norway’s Democratic Voice of Burma have all experienced attacks that disabled or slowed their websites.

The attacks are often timed around sensitive political milestones such as the anniversary of the Saffron Revolution, a 2007 monk-led, anti-government protest that was violently suppressed. Burmese authorities have coupled these technical attacks with brute-force repression.

Exile-run news sites depend on undercover, in-country journalists, who surreptitiously file their reports. This undercover work comes with extreme risk: At least five journalists for Democratic Voice of Burma were serving lengthy prison terms for their work.

Malware attacks: China

Harmful software can be concealed in apparently legitimate emails and sent to a journalist’s private account with a convincing but fake cover message. If opened by the reporter, the software will install itself on a personal computer and be used remotely to spy on the reporter’s other communications, steal his or her confidential documents, and even commandeer the computer for online attacks on other targets.

with a convincing but fake cover message. If opened by the reporter, the software will install itself on a personal computer and be used remotely to spy on the reporter’s other communications, steal his or her confidential documents, and even commandeer the computer for online attacks on other targets.

Journalists reporting in and about China have been victims of these attacks, known as “spear-phishing,” in a pattern that strongly indicates the targets were chosen for their work. Attacks coincided with the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize award to imprisoned writer and human rights defender Liu Xiaobo, and official suppression of news reports describing unrest in the Middle East.

Computer security experts such as those at Metalab Asia and SecDev have found such software is aimed specifically at reporters, dissidents, and non-governmental organizations.

Find more about online censorship in China here.

State cybercrime: Tunisia under Ben Ali

Censorship of email and social networking sites was pervasive in Tunisia under Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, as it has been in many repressive  states. But in 2010, the Tunisian Internet Agency took the effort one step further, redirecting Tunisian users to fake, government-created log-in pages for Google, Yahoo, and Facebook. From these pages, authorities stole usernames and passwords. When Tunisian online journalists began filing reports on the uprising, the state used their login data to delete the material.

states. But in 2010, the Tunisian Internet Agency took the effort one step further, redirecting Tunisian users to fake, government-created log-in pages for Google, Yahoo, and Facebook. From these pages, authorities stole usernames and passwords. When Tunisian online journalists began filing reports on the uprising, the state used their login data to delete the material.

A common tactic of criminal hackers, the use of fake Web pages to steal passwords is being adopted by agents and supporters of repressive regimes. While cybercrime tactics appear to have been abandoned with the collapse of Ben Ali’s government in January, the new government has not relinquished control of the Internet entirely.

Within weeks, the administration announced it would continue to block websites that are “against decency, contain violent elements, or incite to hate.”

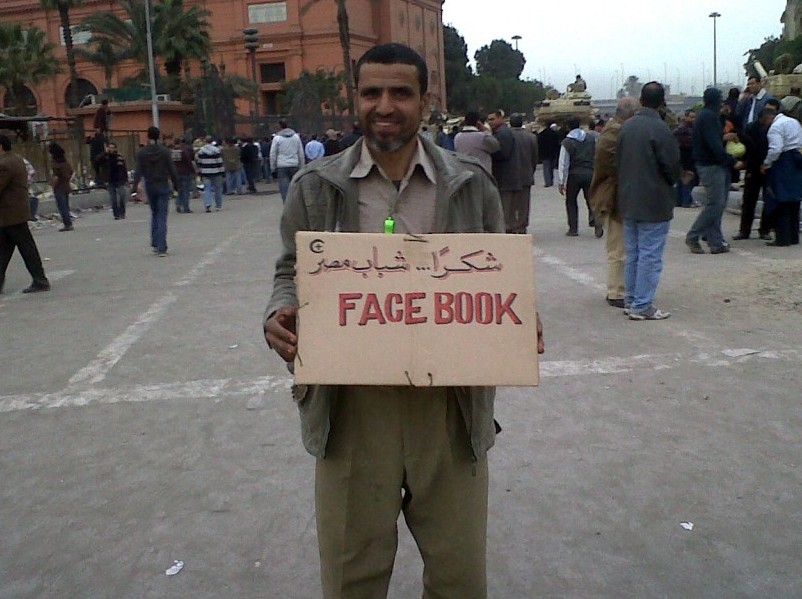

Internet kill switches: Egypt under Mubarak

Desperately clinging to power, President Hosni Mubarak shut down the Internet in Egypt in January 2011, preventing online journalists from reporting to the world, and Egyptia n viewers from accessing online news sources.

n viewers from accessing online news sources.

Egypt was not the first to sever its link to the Internet to restrict news coverage: Internet access in Burma was shut down during a revolt in 2007, and the Xinjiang region of China had either limited or no access during ethnic unrest in 2010.

Mubarak’s crumbling government could not sustain its ban for long; online access returned about a week later. But the tactic of slowing or disrupting Net access has been emulated since that time by governments in Libya and Bahrain, which have also faced popular revolt.

Despite the fall of the Mubarak regime, the transitional military government has shown its own repressive tendencies. In April, a political blogger was sentenced to three years in prison for insulting authorities.

Detention of bloggers: Syria

Despite the spread of high-tech attacks on online journalism, arbitrary detention remains  the easiest way to disrupt new media. Bloggers and online reporters made up nearly half of CPJ’s 2010 tally of imprisoned journalists. Syria remains one of the world’s most dangerous places to blog due to repeated cases of short- and long-term detention.

the easiest way to disrupt new media. Bloggers and online reporters made up nearly half of CPJ’s 2010 tally of imprisoned journalists. Syria remains one of the world’s most dangerous places to blog due to repeated cases of short- and long-term detention.

Ruling behind closed doors in February, a Syrian court sentenced blogger Tal al-Mallohi to five years of imprisonment. She was 19 when first arrested in 2009. Al-Mallohi’s blog discussed Palestinian rights, the frustrations of Arab citizens with their governments, and what she perceived to be the stagnation of the Arab world. In March, online journalist Khaled Elekhetyar was detained for a week, while veteran blogger Ahmad Abu al-Khair was detained for the second time in two months.

Violence against online journalists: Russia

In countries with high rates of anti-press violence, online journalists have become the latest targets. In Russia, a brutal November 2010 attack left the prominent business reporter and blogger Oleg Kashin so badly injured he was placed in an induced coma for a time.

time.

No arrests have been made in the Moscow attack, which is reflective of Russia’s poor overall record in solving anti-press assaults. The attack on Kashin was the most recent in a string of assaults against Web journalists that include a 2009 attack on Mikhail Afanasyev, editor of an online magazine in Siberia, and a 2008 murder of website publisher Magomed Yevloyev in Ingushetia.

Related articles:

No frontiers, new barriers – free speech and attempts to stop it

Threats to internet freedom – political censorship and government control over infrastructure

Burma: cyber attacks against independent news websites

Azerbaijani bloggers sentenced

Russia: new attacks on journalists

Belarus follows China in curbing freedom of information on the internet

Amnesty International Norway calls China to follow Google

Index on Censorship welcomes Google stand on free expression

China: the art of web censorship

Iran: one year after elections – importance of internet and small media

10 tactics on how to defend your rights

Time to entrench media freedom in Kenya’s constitution

Statements:

Youth activists targeted as freedom of expression clampdown continues

Concern with detention and prosecution of Ms Nizovkina and Ms Stetsura