You are leaving Human Rights House Foundation after almost two decades. What is next for you?

I am joining Amnesty Norway as a Senior Advisor where I will work mostly on research on individual cases at risk in Eastern Europe and Central Asia to be used for international campaigns. I think what I will bring with me from HRHF is an understanding of how important it is to respect the work done by the local defenders and their organisations on the ground.

What are you most proud of from your time with HRHF?

I have been privileged to take part in developing the Network of Human Rights Houses.

I am proud of the Houses that I was involved in establishing alongside national coalitions from the Caucasus, Ukraine and Belarus and the connections that we have facilitated between defenders from different countries. Cross-border trainings initiated by Belarusian, Ukrainian and Polish partners more than 15 years ago have been instrumental in raising the skills of young human rights defenders and lawyers in bringing international standards home in several countries.

When it comes to achievements, I will highlight the infrastructure, expertise and capacity that the Network has built on protection over the last decade. This program has made a real difference for so many individuals at risk.

In 2009, the establishment of the South Caucasus Network of Human Rights Defenders was instrumental in building trust across borders in the region. This made it possible for Human Rights House Tbilisi and its partners to meet the needs of partners from Azerbaijan when the crackdown against civil society started in 2013.

Without overstating our role, I do believe that HRHF has built up unique experience assisting partners on the ground and that we have been part of increasing the awareness among Norwegian diplomats on how they can contribute to protecting human rights defenders locally.

What will you take away from your time at HRHF and with the Network?

The strength of solidarity. To visit the coalition in Banja Luka with colleagues from Human Rights Houses Belgrade and Zagreb last June was an illustration for me of the strength of the Network. Being present on the ground when it matters cannot be underestimated.

I will never forget the powerful feeling of the Network coming together in solidarity. I felt it last year in Vilnius in September 2022 when we jointly demonstrated in support of Ukraine and in solidarity with imprisoned colleagues in Belarus in front of the Russian embassy.

I felt it when we walked in the solidarity march from the parliament to the MFA in Oslo in 2015 highlighting portraits of imprisoned and killed defenders. The power of standing together silently side by side at international events at the OSCE and the Council of Europe wearing t-shirts with portraits of Ales Bialiatski and later imprisoned Azerbaijani colleagues so no one in the room could ignore their absence.

It’s the people that I have met during these years that have made the strongest impression on me. I am grateful for the time spent with members of the Network and colleagues from HRHF. I have learnt a lot from all of them.

I have had the privilege of working with so many brave, inspiring and talented human rights defenders in many countries. They have taught me so much. There are too many to mention them all.

I have seen bravery and strong principles from so many in the Network, but also the importance of taking the time to celebrate life even in the darker times.

Mika Danielyan, Tetiana Pechonchik, Lela Tsiskirashvili and Intigam Aliyev are some of several who have taught me that human rights are not only about applying standards in court. It is about developing critical thinking, enjoying music, art, and literature, and being proactive in difficult times.

Mika showed in practice how jazz and human rights are without borders. He introduced me to Miles Davis. When Mika died, Taciana Reviaka from Belarus talked about Mika’s ability to teach his Belarusian colleagues not to give in to despair, as the government was hoping for exactly that.

Sometimes we can be too focused on the situation and not take the time to be with people. I met Ales Bialiatski in Warsaw after his release from prison for the first time. I still regret to this day that I had a return flight that night and I was unable to celebrate his birthday that evening when he asked me to stay. I wish I had rescheduled it. We have to take time for these moments when we can be together.

You have championed the Human Rights House concept for almost two decades. Is it still important today?

The Human Rights House concept is needed more than ever due to the closing of civic space we see in many countries. Human Rights Houses make it more sustainable for coalitions of civil society organisations to work together to protect and promote human rights nationally and internationally.

The structure and focus of each House is unique and reflects local needs and local contexts. But it’s the shared values and long-term partnerships that make the Network special. Recent developments in the region have demonstrated the value of having local civil society present on the ground and an infrastructure in place. I believe the Houses create room for civil society to develop.

How has the human rights situation changed during your time at HRHF?

Sadly, the situation for human rights defenders and human rights has become worse across the Network. Throughout the years, we have experienced the closing of civic space and the emergence of ill democracies in many countries across the Western Balkans and Eastern Europe.

We detected restrictions on freedom of association and assembly and worsening regional trends early on, as the ability to enjoy these rights is practically tested through the Human Rights House concept.

We saw in 2006 how important it was to establish, alongside Belarusian partners, the Belarusian Human Rights House across the border in Lithuania when gatherings inside Belarus became too dangerous. The tools of repression that the Belarusian colleagues faced so early, were later adopted by other authoritarian leaders.

I remember how Barys Zvozskau, the founder of the Belarusian Human Rights House, secretly trained young Azerbaijani activists when he visited Baku on how to cope under interrogation. The Belarusian authorities were ahead of Azerbaijan when it came to repressive tools back then, but sadly, these young activists in Azerbaijan soon made use of this training as the authorities became increasingly harsher towards civil society and dissenting voices.

After the Arab Spring, the Azerbaijani authorities closed down gatherings and independent meeting places. In March 2011, the Human Rights House in the centre of Baku was among one of the first places to be shut down by authorities.

As worrying trends developed in other countries in the region, we understood the importance of having Human Rights Houses.

Alongside Ukrainian partners, we successfully purchased the premises of Educational Human Rights House Chernihiv (EHRHC) amidst Euromaidan, which created a new platform and secured a safe meeting place in Ukraine.

This happened just before Viktor Yanukovych signed the so-called draconian laws to restrict freedom of association and assembly in the middle of January 2014. At that time, no one knew which direction the country would go. The House has become a focal point for human rights education and has contributed to increased awareness about human rights among local authorities in Ukraine.

After the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine started, both EHRHC and Human Rights House Crimea adapted to the needs on the ground and became a shining example of the important role the civil society actors have in Ukraine.

Read more: Working for human rights amidst Russian military aggression.

During my time at HRHF, we have also seen the rise of populism and far-right movements that use disinformation and propaganda to attack critical voices. The attack against the Human Rights House Tbilisi and the PRIDE office in July 2021, for example. In March 2023, Human Rights House Banja Luka became a member of the Network at a critical time as attacks on journalists and those defending LGBT+ groups took place and laws aiming to restrict freedom of expression and association were introduced.

We demonstrated against Russia’s bombing of Chechnya when Putin visited Oslo in heavy snow back in November 2002. This memory is significant to me because this is what we are still fighting today. Putin’s Russia has been responsible for grave human rights violations throughout the entire reign. Network of Human Rights Houses must continue to protest, document and raise awareness of what is going on. We must not let the world forget what Putin, Lukashenka and other authoritarian leaders are doing. They must be held accountable.

Can you share your thoughts on our imprisoned colleagues in Belarus?

In prison, they take away all the things that make you human. The smallest gesture of solidarity from the outside can bring hope – even just a short greeting or an update on the simple things in life – these glimpses of the outside bring life.

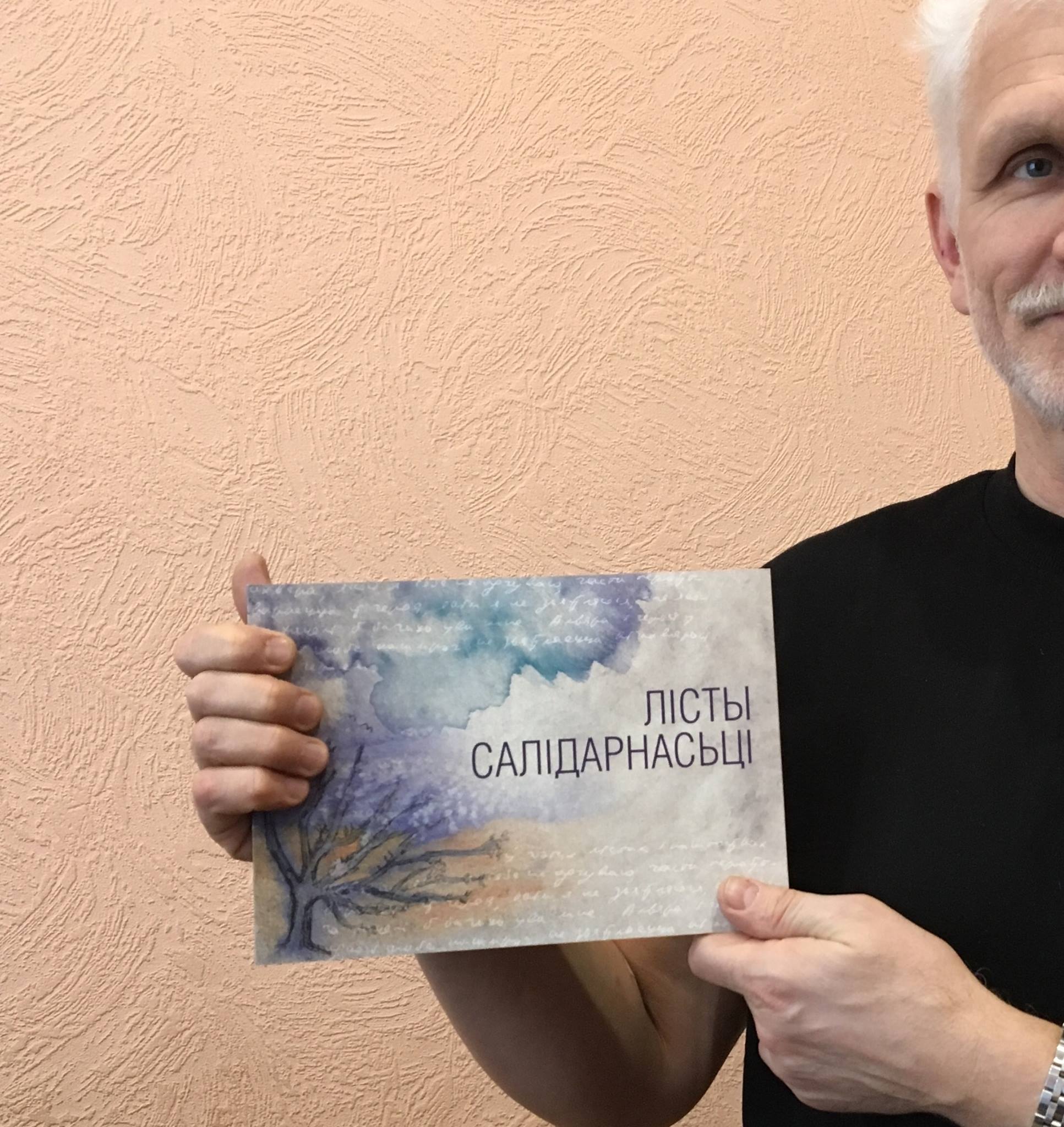

It’s these simple things in life that our imprisoned colleagues are longing for in prison. We must take the time to write to them. Even when we have no guarantee that they get the postcards.

It’s important to write letters and postcards so that the people behind bars know they are not forgotten, so they know that they are recognised for the work they have done. It’s also for the family members to feel this support and know that they are not alone. We have heard this many times from many current and former political prisoners. Most recently from the Belarusian human rights lawyer Leanid Sudalenka of Viasna.

After his release in August 2023, Leanid said he received several thousand postcards at the detention centre – this really matters. He says when they put him in isolation and the postcards stopped, what helped him was that he knew that people were still writing.

Also, postcards and letters are an instrument for protection. Even if the postcards are withheld from prisoners, the guards read them and know that many people care about this person and many people are watching what happens to them.

The last time that Ales Bialiatski was in prison, I made a watercolour painting for him and he told me that even the texture of the paper was so important for him to feel. Like the touch of the real world inside his prison cell.

Why should states, including Norway, continue supporting civil society?

Local civil society is at the forefront of reforms and is pushing the country in the direction of democratic development. While international solidarity and support is important, the role of local civil society cannot be replaced by international actors.

It was Ukrainian civil society actors and ordinary citizens risking their lives to rescue people when the full-scale war started. They were the quickest to act, to help people flee. Local community leaders, journalists, and defenders were the first to document violations and they are still crucial actors to ensure accountability, transparency and further democratic development in Ukraine.

International stakeholders and decision-makers in Norway must not forget that respect for human rights is crucial for security. Russia is a great example – when you do not secure the rights of your citizens and mass violations are happening inside the country for decades, eventually, these problems expand beyond the borders. This is what journalist Anna Politkovskaya warned us about.

What message do you have to the Network of Human Rights Houses and its members, old and new?

Even when it feels impossible, it is important to come together to share, learn, connect, disagree or even confront each other.

In September 2023, Ane Tusvik Bonde joined Amnesty International Norway as a Senior Advisor focusing on the individuals at risk in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. This follows almost two decades with Human Rights House Foundation, where she has played an instrumental role in supporting existing Human Rights Houses, strengthening regional Networks and protection work, and contributing to the Network expansion.