Wyatt was one of the speakers at Norwegian PEN´s Turkey-seminar at the House of Literature 17 January this year. She noted that when she came from Amnesty International to PEN in 1990, there were more writers imprisoned in Turkey than in China. Together China and Turkey led the negative statistics, followed by Vietnam, Cuba and Burma. Last year, all imprisoned Cuban writers were released. This year Burmese writers and journalists are being released. While Turkey is going in the opposite direction and is again back at the top of PEN International’s sad statistics. One factor that worried the about 100 people who attended the seminar.

Imprisonment of writers

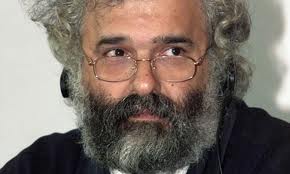

Moderator Alf Skjeseth, journalist, author and former head of the Norwegian Union of Journalist, participated in a Norwegian PEN delegation to monitor court cases against Turkish journalists in 1995. Since last fall, the Turkish authorities have once again started extensive arrests of journalists, academics and intellectuals. Most have been arrested because they, allegedly, had links to Kurdish separatists, lack of evidence of such contacts notwithstanding. Others have been imprisoned because they simply have written about or discussed Kurdish activists and Kurdish interests. Among these was the famous publisher, writer and activist Ragip Zarakolu, director of Belge Publishing House. Zarakolu was arrested and charged with breach of Turkey’s anti-terror laws. However, it has not been proved that Zarakolu has done anything else than participate in normal and legitimate political activities. When Zarakolu was detained by the police 28 October 2011, his son, Deniz, who has also been active in publishing, had already been imprisoned for several weeks.

Moderator Alf Skjeseth, journalist, author and former head of the Norwegian Union of Journalist, participated in a Norwegian PEN delegation to monitor court cases against Turkish journalists in 1995. Since last fall, the Turkish authorities have once again started extensive arrests of journalists, academics and intellectuals. Most have been arrested because they, allegedly, had links to Kurdish separatists, lack of evidence of such contacts notwithstanding. Others have been imprisoned because they simply have written about or discussed Kurdish activists and Kurdish interests. Among these was the famous publisher, writer and activist Ragip Zarakolu, director of Belge Publishing House. Zarakolu was arrested and charged with breach of Turkey’s anti-terror laws. However, it has not been proved that Zarakolu has done anything else than participate in normal and legitimate political activities. When Zarakolu was detained by the police 28 October 2011, his son, Deniz, who has also been active in publishing, had already been imprisoned for several weeks.

Katherine Holle, activist and photographer, married to Ragip Zarakolu, told us how the Turkish government prevents her from having contact with her husband. They do not recognize the U.S. marriage certificate and Holle, who is an American citizen, is denied access to the prison on the same level as all other “foreign visitors”. She said Zarakolu has access to a lawyer, gets his medication and is not subject to torture, but has severe limitations concerning his ability to communicate with the outside world.

Katherine Holle, activist and photographer, married to Ragip Zarakolu, told us how the Turkish government prevents her from having contact with her husband. They do not recognize the U.S. marriage certificate and Holle, who is an American citizen, is denied access to the prison on the same level as all other “foreign visitors”. She said Zarakolu has access to a lawyer, gets his medication and is not subject to torture, but has severe limitations concerning his ability to communicate with the outside world.

Changing Turkish policy on Human Rights

“EU membership is no longer at the center of Turkish politics. Thus, the political and economic need to live up to human standards disappeared, and the state’s dark forces have freer scope,” wrote Norwegian PEN president Anders Heger in his weekly column in the Norwegian daily “Dagsavisen” on 5. November last year. On 9. – 10 January this year, Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg visited Turkey and had talks with Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and President Abdullah Gül in Ankara. On the agenda for the talks were bilateral issues and cooperation, the situation in the Middle East and North Africa, the financial situation in Europe and climate and energy issues. According to Kari Wollebæk from the Ministry Foreign Affairs´ Turkey-desk, human rights were also high up on Stoltenberg’s agenda in Ankara. It has now been agreed that Norway and Turkey will enter into consultations on human rights, coordinated with the ongoing discussions in the Council of Europe, OECD and the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. Themes for the Norwegian-Turkish talks are: 1) freedom of expression, 2) women’s rights and 3) sexual minorities.

“EU membership is no longer at the center of Turkish politics. Thus, the political and economic need to live up to human standards disappeared, and the state’s dark forces have freer scope,” wrote Norwegian PEN president Anders Heger in his weekly column in the Norwegian daily “Dagsavisen” on 5. November last year. On 9. – 10 January this year, Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg visited Turkey and had talks with Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and President Abdullah Gül in Ankara. On the agenda for the talks were bilateral issues and cooperation, the situation in the Middle East and North Africa, the financial situation in Europe and climate and energy issues. According to Kari Wollebæk from the Ministry Foreign Affairs´ Turkey-desk, human rights were also high up on Stoltenberg’s agenda in Ankara. It has now been agreed that Norway and Turkey will enter into consultations on human rights, coordinated with the ongoing discussions in the Council of Europe, OECD and the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. Themes for the Norwegian-Turkish talks are: 1) freedom of expression, 2) women’s rights and 3) sexual minorities.

No progress regarding Kurdish question

The elephant in the room in the Norwegian-Turkish talks will be the Kurdish situation and the rights of the Kurdish people. This question was not officially addressed during the Norwegian Prime Minister’s visit. Abdollah Hejab, representative of Kurdish PEN in Norway, said that 500 Kurdish children were currently detained in Turkish prisons. According to Turkish law, it is not allowed to speak or write publicly about the Kurdish question. Turkey has undergone a positive development in many areas over the past 20 years, including the stabilization of the economy and the recent economic growth, development and strengthening of civil, political institutions and reduced power to the Military Council. But there is still no Turkish law recognizing the rights of about 20 percent of the population, the 14 million Kurds in Turkey.

The elephant in the room in the Norwegian-Turkish talks will be the Kurdish situation and the rights of the Kurdish people. This question was not officially addressed during the Norwegian Prime Minister’s visit. Abdollah Hejab, representative of Kurdish PEN in Norway, said that 500 Kurdish children were currently detained in Turkish prisons. According to Turkish law, it is not allowed to speak or write publicly about the Kurdish question. Turkey has undergone a positive development in many areas over the past 20 years, including the stabilization of the economy and the recent economic growth, development and strengthening of civil, political institutions and reduced power to the Military Council. But there is still no Turkish law recognizing the rights of about 20 percent of the population, the 14 million Kurds in Turkey.

Turkey’s policy towards the Kurds, is assimilation with an iron fist. Since the 1980s, the Kurdish political movements include both non-violent political organizations that are fighting for basic rights for Kurds, and violent, militant rebel groups that require a separate Kurdish state. According to a poll conducted by the Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research (Seta) in 2009, among 59% of the Kurds in Turkey have no desire to establish an independent Kurdish state. Among the Turks, however, more than 70% think that is just what the Kurds want.

Related Stories