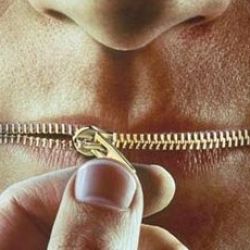

Throughout 2010, the Kazakhstan Government made several promises to decriminalize defamation. However, the legal regime of defamation in the country remains largely unchanged, despite diplomatic and media attention to freedom of expression situation in Kazakhstan during its one-year chairmanship of OSCE and despite some legislative amendments in January 2011.

Throughout 2010, the Kazakhstan Government made several promises to decriminalize defamation. However, the legal regime of defamation in the country remains largely unchanged, despite diplomatic and media attention to freedom of expression situation in Kazakhstan during its one-year chairmanship of OSCE and despite some legislative amendments in January 2011.

Pledges made to gain support

The strong democratic objectives of the OSCE predetermined the serious democratic pledges which Kazakhstan made to gain support for its candidacy. Some of the promises related to improvement of the freedom of expression situation and in particular freedom of the media.

The situation of journalists and the media is equally problematic, there is obvious lack of progress in this area.

Throughout 2010, the Kazakh authorities made several pledges to decriminalise defamation. The Kazakh Criminal Code includes several provisions concerning defamation and insult.

The severe sanctions for defamation and special protection of public officials provided by the Criminal Code suppress free speech and debate on issues of public interests in Kazakhstan. Even more problematic is the fact that these provisions are frequently used against journalists and editors critical of the government. Kazakhstan is of the few countries in Europe and Central Asia where people are imprisoned for defamation.

Dr Agnès Callamard, Article 19 Executive Director, says he is alarmed at the nature and scope of the Criminal Code changes introduced in January 2011 in Kazakhstan an d considers that they will not improve the situation of the media and journalists in the country.

d considers that they will not improve the situation of the media and journalists in the country.

Amendments do not correspond with pledges

Article 19 notes with concern that various pledges for media freedom seem to have been forgotten by the Kazakh authorities after the end of the OSCE chairmanship.

The amendments to the Criminal Code, adopted on 18 January 2011, do not correspond with these pledges and differ from the official draft proposals discussed earlier with national and international experts.

The amendment law introduced two changes to the legal regime of defamation.

The major change is the establishment of administrative responsibility for defamation and insult and the setting up of a hierarchy in the regimes of criminal and administrative responsibilities for these acts.

Criminal responsibility for defamation and insult is not removed from the Criminal Code, but it can be sought only after an administrative penalty has been imposed for the same offence. This means that complaints for defamation and insult should be first examined under the regime of the Code of Administrative Offences. If an individual conducts again the same offence within one year after having been found administrative liable for the same act, he/she can be prosecuted under the Criminal Code.

The minor change concerns the system of sanctions for defamation and insult. While fines, prohibition to engage in public work, correctional labour and imprisonment remain, arrest for libel and insult is removed for the general form of defamation.

With respect to the special form of defamation – insult of the president, and defamation of judges and other representatives of the judiciary – arrest is replaced with “restriction on liberty” for up to one and two years respectively, or deprivation of liberty for the same period. “Restriction on liberty” consists in imposition on the person convicted by the court of certain duties which restrict his freedom and is carried out in the place of one’s residence under the supervision of the specialised body without isolation from the society for a period from one year up to five years.

president, and defamation of judges and other representatives of the judiciary – arrest is replaced with “restriction on liberty” for up to one and two years respectively, or deprivation of liberty for the same period. “Restriction on liberty” consists in imposition on the person convicted by the court of certain duties which restrict his freedom and is carried out in the place of one’s residence under the supervision of the specialised body without isolation from the society for a period from one year up to five years.

Downsides

Although designed to be applied in place of criminal responsibility, the introduction of administrative liability for defamation and libel does not improve the situation of journalists and media for the following reasons:

Peculiar legal regulation

The current legal regime requiring imposition of administrative penalty before recourse to criminal liability, known as administrative praejudicium (prior administrative judgment) is a peculiar legal regime existing only in few former Soviet Union states.

This regime does not set a clear distinction between crimes and administrative offences because it focuses on level of danger to society. In contrast, in Europe administrative offences are distinguished from crimes on the basis of their consequences whereby the effect of administrative offences is on public governance and order.

Finally, since there is no justification for this regime, the regime violates the constitutional principle of equal treatment before the law in as much as for the same act some individuals can be held responsible under Criminal Code while others are held responsible under the Code of Administrative Offences.

Lack of clarity

The regulation of the new legal regime is very vague. International law requires that restr ictions on the right to freedom of expression, such as those related to defamation and insult, are clearly defined. This is not the case with the amendment to the Criminal Code.

ictions on the right to freedom of expression, such as those related to defamation and insult, are clearly defined. This is not the case with the amendment to the Criminal Code.

Although it provides that the new regime of administrative praejudicium applies to crimes that do not represent “big danger to society”, it does not specify these crimes. The confusion grows bigger due to the fact the Criminal Code does not contain other similar references.

The Code of Administrative Offences does not define offences of defamation and insult. It means that other administrative offences should be interpreted widely to apply to cases of defamation and insult. This runs against the principle of rule of law and creates risks for abuses and inconsistent application of the law.

Finally, it is unclear which body is competent to establish defamation and libel as administrative offences. Administrative offences are typically determined by administrative procedures carried out by administrative bodies. If the same applies to defamation and insult then administrative authorities will be granted with unlimited powers to restrict freedom of expression.

Problematic administrative regime for defamation and insult

In general administrative responsibility is regarded as less severe than criminal responsibility. However, the Kazakh Code of Administrative Offences, which regulates administrative responsibility, is not in compliance with international standard.

The regime of administrative praejudicium will not improve the situation of journalists and media in Kazakhstan  because the Code of Administrative Offences does not incorporate the principle that any sanctions on the right to freedom expression must be necessary and proportionate to the harm done.

because the Code of Administrative Offences does not incorporate the principle that any sanctions on the right to freedom expression must be necessary and proportionate to the harm done.

Moreover, the penalties stipulated in the Code of Administrative Offences are harsh. They include high fines and administrative arrest, which according to international law is a disproportionate restriction to freedom of expression in cases of libel and insult.

Failure to remove higher protection for public officials

The January 2011 amendment did not address key discrepancies between the Criminal Code and international freedom of expression standards identified by international experts. The president, MPs and state officials are still given higher protection against defamation and insult. The Criminal Code penalties for defamation remain harsh. Some of them like restriction of liberty and deprivation of liberty are clearly in violation with international law.

Recommendations

Article 19 calls on the Kazakhstan Government to address immediately these issues and adopt legislation that fully complies with international freedom of expression standards. In particular, they recommend that:

• The Kazakh Government remove the regime of administrative praejudicium and decriminalise insult and defamation. Alternatively, replacement of the new regime of administrative praejudicium with release of criminal responsibility with imposition of administrative fine should be considered;

• The Kazakh judicial authorities introduce comprehensive trainings for judges and law enforcement officials to protect freedom of expression when implementing criminal and administrative code;

expression when implementing criminal and administrative code;

• International organisations carry out a rigorous analysis of the new regime of administrative praejudicium and its affect on freedom of expression;

• National NGOs and media carry out monitoring of the application of the new regime of defamation and libel and report of the situation of journalists and media.

Related articles:

NHC: Norway must address contradictions in Kazakhstan’s OSCE chairmanship

Kazakhstan’s OSCE chairmanship: Kazakhstan must implement its Human Rights obligations

OSCE chair Kazakhstan ignores OSCE commitments

Jailed Kazakh human rights defender treated unequally

Kazakhstan: Protests against court decision on Evgeniy Zhovtis

Human rights challenges in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan: referendum rejected, real test for democracy – free and fair elections