Burma’s military regime has confirmed that it will hold elections this year for the first time since the nullified 1990 elections, though the date has not been announced. The Election Law was released on 8 March, and through various articles it is apparent that there will be little space for democratic parties, and genuine inclusion of ethnic groups. Moreover, the military regime, the Union Solidarity and Development Association (USDA), and its proxy parties have already begun ‘electioneering’ as well as harassing and restricting opposition before the election.

Burma’s military regime has confirmed that it will hold elections this year for the first time since the nullified 1990 elections, though the date has not been announced. The Election Law was released on 8 March, and through various articles it is apparent that there will be little space for democratic parties, and genuine inclusion of ethnic groups. Moreover, the military regime, the Union Solidarity and Development Association (USDA), and its proxy parties have already begun ‘electioneering’ as well as harassing and restricting opposition before the election.

Election scenarios

The military regime has shown little evidence that it will concede to the demands of the people of Burma and the international community before the elections, in fact they have shown quite the opposite. It is impossible to say for certain what will happen this year in the lead up to the elections, but, according to MDREN, there are a few possible scenarios.

Scenario 1: Elections without any changes. The ruling junta will go ahead and hold elections without any concession to The National League for Democracy (NLD), democracy groups, ethnic communities or international requests. After the election law is announced it will force political parties to choose participation or deregistration. Most parties that will participate will be proxy parties of the regime. Any independent reporting, political activity, or expression will be suppressed resulting in no real opposition. It is likely international election monitors will not be allowed, and if they are, will be highly restricted by the military regime. After the election fundamental problems will remain unchanged while the military role will be institutionalized through the constitution.

Scenario 2: Regime makes weak concessions. The junta could make surface-level concessions in the lead up to the elections, such as releasing a few political prisoners, making repeated public statements ensuring free and fair elections, or allow some regional election monitoring groups, etc. However, these acts are not going to create political atmosphere and election that will have enough democratic integrity.

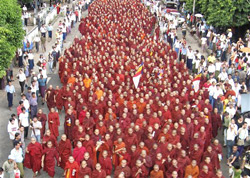

Scenario 3: Mass civil unrest happens and elections are postponed. Many in the general public are disgruntled with the plunging economy and the difficulty of maintaining daily existence  for their families. Mass civil unrest could occur, similar in size and scale to the Saffron Revolution, leading to the military regime to postpone elections. Moreover, the military regime is pressuring ceasefire-armed groups to transform into border-guard forces and most of the larger ethnic armies are refusing. Most of the non-ceasefire armed groups have also dismissed the elections, while the military regime is increasing efforts to eradicate opposition. There is a chance that civil war could break out.

for their families. Mass civil unrest could occur, similar in size and scale to the Saffron Revolution, leading to the military regime to postpone elections. Moreover, the military regime is pressuring ceasefire-armed groups to transform into border-guard forces and most of the larger ethnic armies are refusing. Most of the non-ceasefire armed groups have also dismissed the elections, while the military regime is increasing efforts to eradicate opposition. There is a chance that civil war could break out.

The largest obstacle to change – undemocratic Constitution of 2008

The 2008 Constitution that the new government will be founded on is the main problem that will guarantee military supremacy. Whereas in the 1990 election, where the party that won the most votes could then create a new constitution, in this election, even if independent leaders are able to be elected they will have to work within an undemocratic constitution that holds little hope of being able to amend.

According to MDREN, The constitutional drafting process in Burma in 2008 failed to meet minimum international standards. It excluded democratic participation, was conducted in secrecy and heavily manipulated by the military regime. The military government, now called the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) also criminalized open criticism of the process. Moreover, until April 2008, a month before the referendum, it was i llegal to even discuss constitutional matters outside of the National Convention.

llegal to even discuss constitutional matters outside of the National Convention.

The constitutional referendum failed to meet a single basic international standard for a free and fair referendum process. The violations included: ballots were not secret; the SPDC and its agents used threats, coercion, misinformation, deception, and violence to sway or force voters to approve the draft constitution; voters did not feel that they were provided adequate information to develop an informed opinion on the constitution; the SPDC systematically stifled all independent and opposition media coverage; the SPDC refused to allow independent electoral monitors to observe the referendum voting in Burma.

Despite international pressure to cancel or postpone the referendum following the devastation of Cyclone Nargis, the regime claimed a 92% approval rate for the referendum, which took place on May 10 and 24.

Undemocratic content of the 2008 Constitution

In theory, creation of a new constitution leading to elections could form the basis of building security, national reconciliation and democracy. It is not unusual to adopt a new constitution in the context of civil conflict. Many civil disputes stem from the structure of the state, the distribution of power, and access to national resources – the very matters dealt with in a constitution. In the case of Burma, however, the new Constitution diminishes the likelihood of reconciliation and democracy.

The Constitution is substantively problematic because it ensures the military maintains implicit and explicit control over all of Burma’s institutions. Moreover, rather than reflecting the will of the people while protecting the vulnerable, the constitution exposes ethnic minorities and political opponents to considerable risk. Here are some examples illustrating mentioned before.

According to the new Constitution, twenty-five percent of all seats are allocated for the military, which will give them veto power on any legislation process that needs more than 75% approval vote. Because the military makes up 25% of parliament, effectively, appointment to the presidency requires their support. Once in office, the president yields enormous powers, including the power to appoint most positions of power. The relationship between the Commander in Chief and the President is also problematic and structured to ensure the military maintains control over Burma’s institutions. The Commander in Chief can remove the President. Some Presidential actions require approval of Commander in Chief. During periods of “state emergency” the Commander in Chief can supersede both President and Parliament. The Commander in Chief is not appointed by parliament, has no period of tenure, and there is no procedure for removal.

The judicial system, ethnic groups, human rights and women rights

The Burmese judiciary consists of ordinary courts, the courts martia l and the Constitutional Tribunal. Overall, the procedure for the appointment of judges is highly politicized. The constitution does not stipulate rules about the independence of the judiciary, and the Supreme Court does not have the power to interpret the Constitution.

l and the Constitutional Tribunal. Overall, the procedure for the appointment of judges is highly politicized. The constitution does not stipulate rules about the independence of the judiciary, and the Supreme Court does not have the power to interpret the Constitution.

The ethnic conflicts that have been happeningn in Burma for decades stem from a constitutional crisis unable to deal with Burma’s ethnic plurality. Ethnic minorities have long agitated for a truly federal system ever since they were persuaded to join Burma at the time of independence. The fact that the 2008 Constitution stipulates that all regional and self-administered areas are subject to the rule of the national executive and legislature effectively abolishes the vision of a federal government structure in Burma. The complex structure of territorial division of the country hide the highly centralized nature of the state and administration. In other words, the 2008 constitution will centralize control over ethnic minority areas further. On the issues of language, culture and religion, crucial to minorities, little authority is given to regional or self-administered communities.

The constitution infringes on the fundamental human rights of the people in the name of state security and public tranquility. Nothing is said, for example, about rights of minorities, children, and the disabled. Most rights are also confined to citizens of Burma – the definition of citizen in the constitution is questionable and appears to be politically motivated to exclude opponents of the regime. It is likely that the judiciary will not be able to protect human rights. No other institutions, like a human rights commission or ombudsperson, is provided or envisaged.

be politically motivated to exclude opponents of the regime. It is likely that the judiciary will not be able to protect human rights. No other institutions, like a human rights commission or ombudsperson, is provided or envisaged.

Women are disqualified from holding many positions of power because many posts require prior military service. This includes the Presidency, Vice-Presidency, and key ministries. Though the constitution says that there will not be discrimination based on sex in regards to appointments, the constitution also adds, “However, nothing in this Section shall prevent appointment of men to the positions that are suitable for men only.”

Election law: neither free nor fair

On 8 March, the Burma’s military regime announced it had enacted the election law for this year’s polls, but did not set a date for the general election. Here are the most notable points from the laws:

– The Election Commission will be handpicked by the regime;

– Political Parties Registration Law bans democracy organizations or armed groups who oppose the junta, and those receiving support from outside Burma, as well as those who have served prison sentences or are appealing a sentence. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and many democracy and ethnic leaders will be unable to participate;

– All political parties must pledge to abide by and protect the 2008 Constitution;

– All political parties, including existing parties within 60 days must register with the Commission. The Commission will have the authority to approve or reject any registration;

authority to approve or reject any registration;

– The elections may not be held in many ethnic areas controlled by armed ethnic organizations that have signed cease-fire agreements but failed to transform into the Border Guard Force under the control of the regime’s Army, or in other ethnic areas;

– According to the Constitution, in both houses of Parliament, military may take more than 25% of seats;

– 1990 Election results are Nullified.

Possible implications of the regime’s sham democratization

The 2008 constitution and the upcoming election is not a step towards democratization of Burma’s political process, according to MDREN. While the military junta portrays the SPDC as a transitional body whose powers will cease to exist once the 2010 elections are over, the special privileges, representations, and immunities in state institutions and for the military as listed in the 2008 constitution will prevent any true transitional efforts. The fact that it is very difficult to amend the 2008 constitution is only one sign of the determination of the military to prevent full democracy and participation and the protection of rights; moreover, in the Election Law the condition was set that all political parties must pledge to the Constitution.

There is a strong possibility that the unresolved conflicts within Burma will continue or even aggravate because of the blatant exclusion of ethnic nationalities in the constitution. Towards non-ceasefire groups, the military regime has stepped up their attacks against ethnic communities, as well as armed forces, seeking to finally eradicate any opposition before the election.

Possible solutions and demands

Genuine political dialogue involving democracy organizations and ethnic nationality groups has never been realized in Burma since 1962 and continues to be prohibited in the lead up to the election.

The democracy movement inside and outside Burma has stated on numerous occasions that they do not accept the military regime’s roadmap to democracy. According to them, while the democracy movement has stated its willingness to engage in dialogue, the military regime must meet crucial benchmarks to demonstrate sincerity. MDREN’s demands are: 1) Release of all political prisoners; 2) Genuine inclusive political dialogue and a review of the 2008 constitution; 3) Cessation of attacks and human rights violations.

MDREN asks the international community to continue to pressure the military regime to meet these crucial benchmarks in order to truly bring the country towards national reconciliation. They ask the United Nations Security Council to pass an Arms Embargo to hinder the military regime from its brutal offensive against civilians and begin a Commission of Inquiry to investigate crimes against humanity. As it did with the South African Constitution in 1984, the UN Security Council should pass a resolution to declare Burma’s racist 2008 Constitution null and void.

MDREN asks the international community to continue to pressure the military regime to meet these crucial benchmarks in order to truly bring the country towards national reconciliation. They ask the United Nations Security Council to pass an Arms Embargo to hinder the military regime from its brutal offensive against civilians and begin a Commission of Inquiry to investigate crimes against humanity. As it did with the South African Constitution in 1984, the UN Security Council should pass a resolution to declare Burma’s racist 2008 Constitution null and void.

In light of Burma’s serious breach of the principles of the ASEAN Charter, ASEAN leaders make serious measures to address the breach of principles, MDREN calls ASEAN to suspend energy related resource extraction projects.

They also call the EU to send its Burma envoy, US – appoint their envoy and dispatch immediately. In their eyes these envoys should work in coordination with each and in cooperation with UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. According to them, US, UK and EU must impose stronger targeted sanctions.

Background

The Movement for Democracy and Rights for Ethnic Nationalities (MDREN) is an alliance of major Burmese ethnic and democracy parties both exiled and within Burma. The movement came together around negotiations for the “Proposal for National Reconciliation“, and the convention to formalise this document, in Jakarta in August, 2009. The group seeks to begin the process of transition towards democracy, freedom and peace in Burma.

You can download the MDREN document from Realted links (on the right).

There are more reports, statements, letters of concern by different organizations and institutions concerning upcoming election in Burma. You can find them on the “Burma Campaign UK” web-site.

Documents: