– We are happy that the Russian government now recognizes the European Court of Human Rights as one the most important institutions for protecting human rights, said Engesland.

The Russian State Duma voted 15 January 2010 in favor of a draft law ratifying Protocol 14 of The European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR), after delaying ratification for more than three years.

The Russian State Duma voted 15 January 2010 in favor of a draft law ratifying Protocol 14 of The European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR), after delaying ratification for more than three years.

– Russian authorities have given an important message that they want an effective European Court on Human Rights. About 30% of the applications to the Court are from Russian citizens, says Ekeløve-Slydal, left.

Most of the pending cases in the ECHR originate from the Russian Federation.

Protocol 14 simplifies the Court’s procedures on deciding admissibility of cases and on handling obvious cases. The ratification has been a long-awaited step, as the Russian Federation is the last country to ratify the protocol.

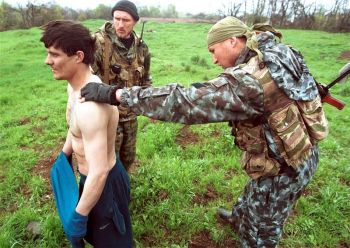

Mostly the Chechen Republic abuses

By November 2009 there have been 31 850 cases from the Russian Federation, which is a total of 27.3 % of all the cases in the ECHR. Most of the cases concern human rights abuses in the Chechen Republic.

At least 115 judgments from ECHR have held the Russian Federation responsible for enforced disappearances, extrajudicial executions and torture, and for failing to investigate these crimes properly. Ratifying Protocol 14 will hopefully open up for the reform of the  ECHR and increase the effectiveness of the court.

ECHR and increase the effectiveness of the court.

As yet, the Russian Federation has been paying the compensations, according to the judgments, without investigation of the cases. Ratifying protocol 14 will hopefully change this practice.

Protocol 14 was adopted in 2004 as part of a reform package in order to ensure that the Court would have the capacity to handle an increasing backlog of cases.

More than 90% of the applications received by the Court are deemed inadmissible for various reasons. However, taking decisions on admissibility takes a large part of the Court’s capacity. Protocol 14 is therefore important in that it frees Court resources to handle serious human rights cases.

Appelants unprotected The Norwegian Helsinki Committee is arguing that focus should not only be on Court’s effective functioning but also on protection of appellants, witnesses and lawyers involved in particularly serious cases.

The Norwegian Helsinki Committee is arguing that focus should not only be on Court’s effective functioning but also on protection of appellants, witnesses and lawyers involved in particularly serious cases.

It is positive that the government of the Russian Federation on 2 October 2009 adopted a Witness Protection Program for 2009-2013. However, there might still be a need for supplemental measures.

Such a protection mechanism could be based on agreements between the Court and/or the Council of Europe and member states that they will receive and provide temporary protection to persons at risk because of their involvement in cases before the Court.

The next important venue for discussing the future of the Court will be at the 18-19 February 2010 Interlaken Conference. The purpose of this conference is to have the Council of Europe member states to reaffirm their commitment to the protection of human rights in Europe and to draw up a roadmap for the future development of the Court.

Conscience of Europe At 50 years old, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg is sometimes held up as a model for the rest of the world – the most efficient regional court devoted to protecting individual human rights against abuses of state power.

At 50 years old, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg is sometimes held up as a model for the rest of the world – the most efficient regional court devoted to protecting individual human rights against abuses of state power.

It was designed after Second World War as a part of efforts to ensure that democratic Europe would stay democratic, peaceful and respectful of individual dignity. It sees itself as “the conscience of Europe”.

However, Central and Eastern Europe remained outside the Court until after the democratic revolutions of 1989 and 1991. In a few years afterwards, almost all of Europe became part of the system, giving about 800 million people the option of filing an application asserting that one of the 47 member states of the Council of Europe had violated their human rights (as defined in the European Convention on Human Rights and a few additional protocols).

Stop “legal nihilism” the Russian Federation became part of the system in 1996.

the Russian Federation became part of the system in 1996.

However, the future of the Court is now the subject of highly sensitive debates that until the 15 January 2010 decision of the Russian State Duma also has been seen as a test of Russia’s commitment to human rights and democracy.

The court have issued more than 10,000 rulings that have held member states to account for torture, unlawful killings, stifling freedom of expression and a range of other violations – often to the great discomfort of the countries involved.

The Russian decision to ratify Protocol 14 was an important breakthrough in Russia’s relationship with the Court. President Dmitry Medvedev, above, has spoken of the need to end “legal nihilism” in the Russian Federation and secure the independence of its courts. The European Court of Human Rights could be seen an important contributor to abolishing this state of legal nihilism. A strong Court is therefore in the best interest of the Russian Federation.

Protocols 14 and 14bis

Protocol 14 was adopted in 2004. Among its main features is that:

- A single judge can decide on the admissibility of a case (currently, three judges decide) (Article 7)

- A committee of three judges may render a judgment on the merits, “if the underlying question in the case concerning the interpretation or the application of the Convention or the Protocols thereto, is already the subject of well-established case-law of the Court” (Article 8)

- A case may be deemed inadmissible if “the applicant has not suffered a significant disadvantage, unless respect for human rights as defined in the Convention and the Protocols thereto requires an examination of the application on the merits and provided that no case may be rejected on this ground which has not been duly considered by a domestic tribunal.” (Article 12)

- “If the Committee of Ministers considers that the supervision of the execution of a final judgment is hindered by a problem of interpretation of the judgment, it may refer the matter to the Court for a ruling on the question of interpretation. A referral decision shall require a majority vote of two thirds of the representatives entitled to sit on the Committee.” (Article 16)

- “If the Committee of Ministers considers that a High Contracting Party refuses to abide by a final judgment in a case to which it is a party, it may, after serving formal notice on that Party and by decision adopted by a majority vote of two thirds of the representatives entitled to sit on the Committee, refer to the Court the question whether that Party has failed to fulfill its obligation under paragraph 1.” (Article 16)

Because the Russian rejection of Protocol 14 effectively obstructed the reform process of the Court, a Protocol 14bis was adopted in May 2009.

Pending the ratification of Protocol 14 itself, 14bis allows the Court to implement revised procedures in respect of the states which have ratified it.

Protocol 14bis will cease to have any effect as soon as Protocol 14 enters into effect.