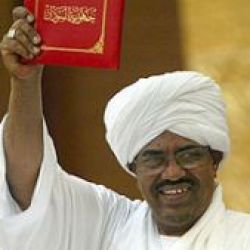

The Ugandan government’s U-turn on Gen. Bashir, whose arrest is being sought by the International Criminal Court over charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Darfur region in his country, came during a visit to Kampala by the ICC chief prosecutor, Mr Luis Moreno-Ocampo.

Addressing a joint press conference in Kampala yesterday with Mr Ocampo, International Relations Minister Henry Okello Oryem acknowledged that the government has received a warrant of arrest for Gen. Bashir, who is the first sitting president to be indicted by the court. “An arrest warrant for Bashir has been deposited at the office of the Solicitor General,” Mr Oryem said. “It’s up to [Inspector General of Police] Gen. Kale Kayihura to arrest him. “It’s a legal obligation for Uganda to arrest Bashir were he to come to Uganda. Bashir should know this before he comes,” he said, adding that the arrest will “eventually” happen.

Uganda was the first country to refer a matter to the ICC when it successfully procured indictments for LRA rebel leader Joseph Kony and his top lieutenants. The government has, however, blown hot and cold on the matter, invoking the LRA indictments to force the rebels to the unsuccessful peace talks in Juba last year, while supporting a decision by the African Union (AU) not to respect the warrants against Gen. Bashir.

The government has a leg on either side of the fence; it says it remains committed to the ICC and plans to strengthen it – but also claims to share the AU’s views. Mr Ocampo, right, said yesterday that the AU was not a party to the Rome Statute and that Uganda, which is, is not bound by the “political” discussions meant to shield Bashir from trial in The Hague. Mr Ocampo said Uganda would be obliged to arrest the Sudanese president, and cited the case of South Africa where he said the possibility of detention stopped him (Bashir) attending President Jacob Zuma’s inauguration in May.

The government has a leg on either side of the fence; it says it remains committed to the ICC and plans to strengthen it – but also claims to share the AU’s views. Mr Ocampo, right, said yesterday that the AU was not a party to the Rome Statute and that Uganda, which is, is not bound by the “political” discussions meant to shield Bashir from trial in The Hague. Mr Ocampo said Uganda would be obliged to arrest the Sudanese president, and cited the case of South Africa where he said the possibility of detention stopped him (Bashir) attending President Jacob Zuma’s inauguration in May.

“South Africa informed Bashir that he could be invited to President Zuma’s inauguration, but if he is there he could be arrested,” the ICC prosecutor said. “It’s a legal obligation not a political decision, it’s a court decision and Uganda, South Africa and the 30 African (member) state parties have this legal obligation, it’s clear,” he said. Last Friday, after this newspaper broke the story of Bashir’s intended visit, the Foreign Affairs ministry maintained that the Sudanese leader was welcome. Foreign Affairs Minister Sam Kutesa said: “The AU is not working outside the Rome Statute. For durable peace [other] remedies need to be exhausted first. These are just accusations [against Bashir] even the prosecutor has to prove them.”

The government now finds itself between an ocean of responsibility and a serpent of political pragmatism. The government has accused Gen. Bashir of supporting the LRA rebels – in retaliation for Kampala’s support for the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army – but is keen not to reignite the regional tensions by arresting or humiliating the Sudanese leader.

Khartoum has given no indication as to whether President Bashir plans to honour the invitation to the Smart Partnership Dialogue later this month. The Sudanese leader has, in a sign of defiance, visited several countries since the warrants of arrest were issued – but his visit to Uganda would the first to a country that has ratified the Rome Statute which set up the ICC and a test of Kampala’s political resolve. Uganda is currently representing Africa as a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council and is expected to host an African Union Summit in Kampala next year.