Tetiana Pechonchyk is the Head of the Board of ZMINA Human Rights Centre, member organisation of Human Rights House Crimea & Educational Human Rights House Chernihiv.

This article can be read in Ukrainian via ZMINA Human Rights Centre.

What are the current priorities and challenges for Ukrainian human rights organisations three years into the full-scale war and 11 years since the Russian occupation of Crimea?

The biggest challenge is the sheer scale and severity of crimes committed by the Russian Federation—not only since the full-scale invasion but since 2014.

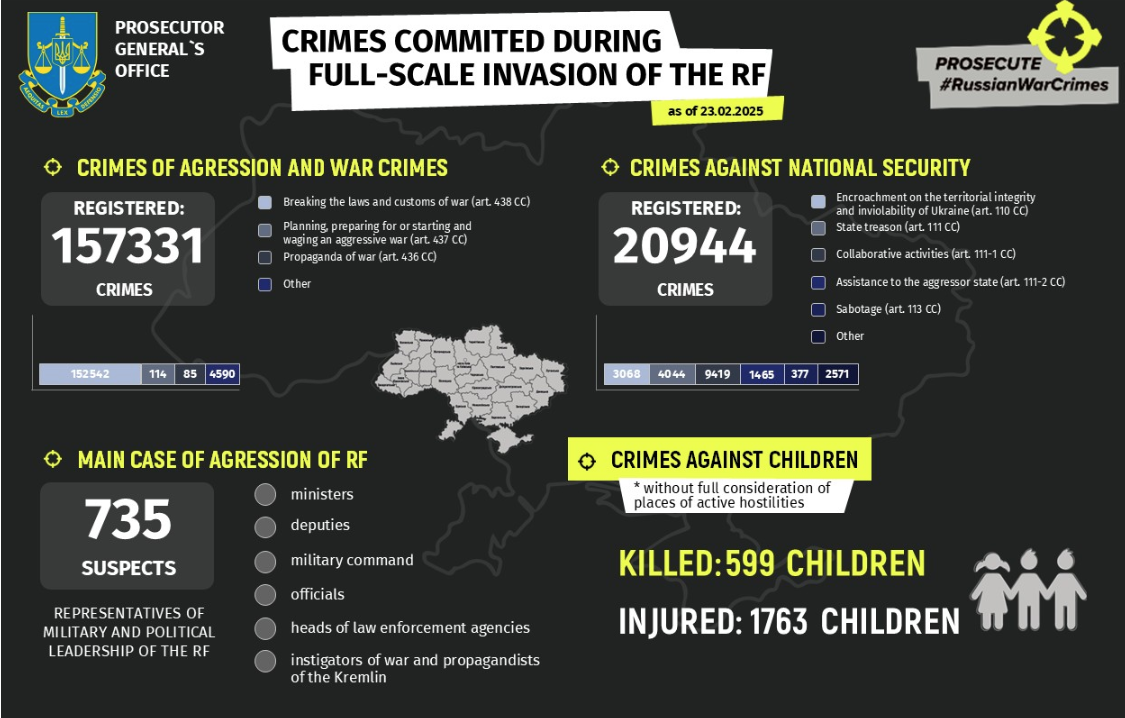

The Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine has registered over 150,000 criminal proceedings regarding alleged war crimes committed since 24 February 2022.

This is an overwhelming number — an avalanche of atrocities that no law enforcement system, even in the most developed country, could handle alone. Given the scale, complexity, and sheer number of cases, investigations could take decades.

It is also clear that a significant portion of these crimes will never be fully investigated, nor will those responsible be identified. This creates frustration among victims. During field missions, we often hear from survivors of war crimes and crimes against humanity that they do not believe justice will be served. Many perpetrators have taken steps to avoid identification, and some may no longer be alive.

However, for victims, justice remains crucial — if not against the direct perpetrators, then against those who gave the orders or whose silent approval enabled these crimes: their commanders, their commanders’ superiors, and the highest leadership of the Russian Federation.

On the mechanisms for the release of civilian hostages

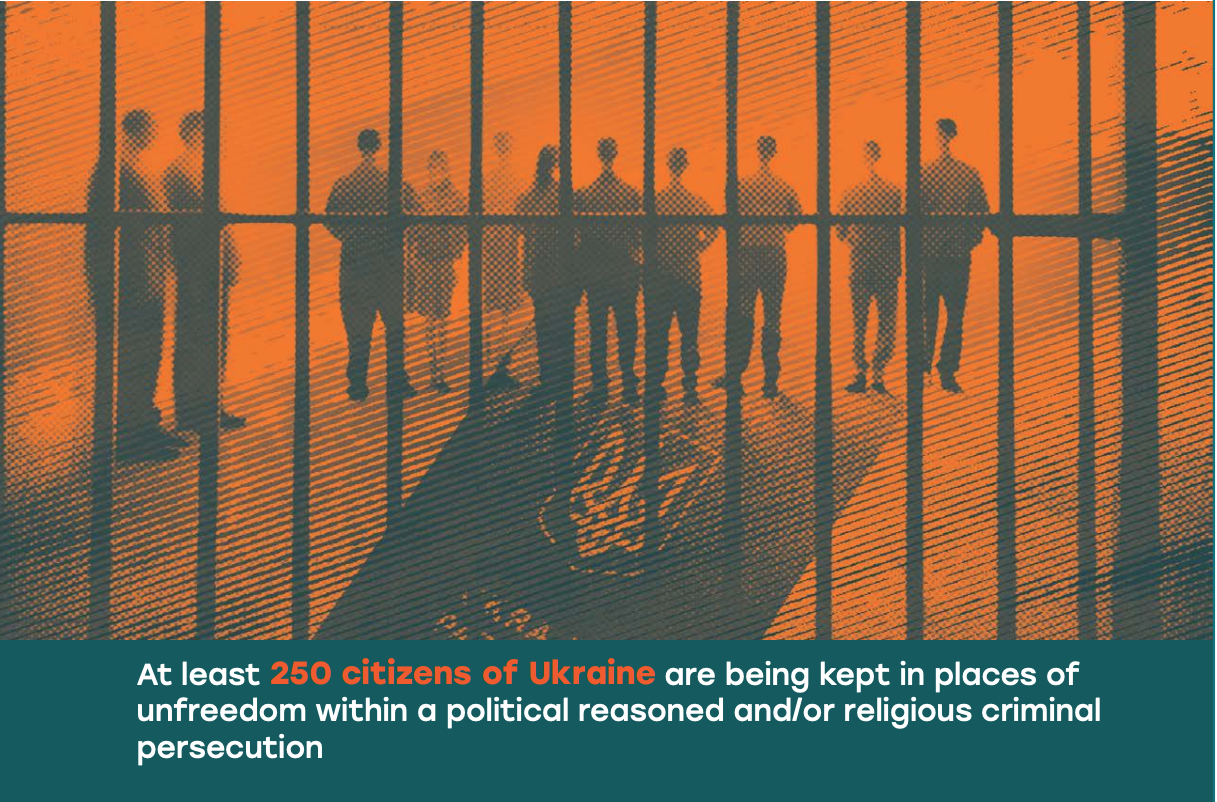

Efforts [to create the mechanisms for the release of civilian hostages] have been ongoing for a long time, but I remain sceptical about whether a new mechanism can be created to secure civilian release when Russia, as an occupying state, blatantly and repeatedly violates international humanitarian law and human rights. Many civilians are held incommunicado, with Russia refusing to confirm their whereabouts, while others face entirely fabricated charges.

What mechanisms could possibly force Russia to release them? Ukraine, after all, has not been detaining civilians in Russian regions like Kursk and filling its prisons with them. There is no exchange of civilians for civilians, as Ukraine operates within the framework of the law. If one state abides by legal norms while the other does not, what kind of mechanism can we realistically discuss?

Currently, the only viable options are mechanisms of informational and political pressure. Some cases lead to targeted negotiations, such as the release of Nariman Dzhelyal. These mechanisms work on an individual basis.

As long as the full-scale war continues and Russia refuses to release civilians — or insists on exchanging them for Russian prisoners of war — Ukraine cannot accept such terms. If Ukraine were to engage in such exchanges, Russia could simply detain thousands more civilians in occupied territories, creating an endless cycle.

Unfortunately, even if the war stops and some hostages are released, many will likely remain imprisoned in Russian jails. We might not even know their whereabouts, as Russia does not disclose this information. This situation is reminiscent of the Soviet-era Gulag [system], where detainees were continuously transferred further east. We already see that some political prisoners are being moved to Russia’s remote regions, where they could be held for decades. In fact, we may not even know about some of these individuals at all.

Similarly, today, we have no clear data on how many civilians are imprisoned by Russia. The Ukrainian Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War has estimated around 14,000 civilian detainees, but only less than 2,000 cases are confirmed with verifiable information. This means we lack knowledge about thousands of people—whether they are alive, whether they are held in prisons.

There are over 60,000 people officially missing — including both military personnel and civilians.

There is also an understanding that if the war is frozen again, it may provide opportunities for the release of civilians, particularly as so few have been freed over the past three years. However, it is difficult to predict what Russia might demand in return. It is clear that it will do everything in its power to halt investigations and prevent accountability. For instance, Russia could insist that Ukraine halts national investigations into suspected Russian war criminals in exchange for releasing Ukrainian civilians. This presents an enormous challenge — especially for victims, who may not necessarily seek financial compensation from Russia but demand justice.

How would you assess the evolution of the human rights situation in Crimea controlled by Russia for 11 years?

Human rights and international humanitarian law violations in Crimea continue. Since Russia occupied Crimea in February 2014, different waves of escalation have occurred, each with its own dynamics.

Following the full-scale invasion in February 2022, the situation worsened significantly. The widespread practice of enforced disappearances re-emerged in Crimea, this time also affecting a large number of individuals abducted from Ukraine’s southern regions, particularly Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. Many were transferred to detention facilities in Crimea, where they were held incommunicado.

Russia has continued imprisoning independent journalists on politically motivated charges while also significantly increasing pressure on lawyers, silencing them too. Meanwhile, the number of cases has surged, leaving the remaining lawyers unable to provide legal defence to everyone in need. Additionally, there has been a gradual increase in the number of detained and imprisoned women.

“Russian military aggression followed by the full-scale invasion is all due to impunity, which began with Crimea… we still don’t know where it might lead in the end.” Interview with Crimean human rights defenders

Building Resilience of Civil Society in Ukraine: Wellbeing as a Cornerstone of Sustainability

When I communicate with [political prisoners] and their relatives, I tell them that [legal action] will not significantly affect their immediate situation, but it must be done. Interview with human rights lawyer Serghiy Zayets

One of the speculated scenarios regarding possible peace negotiations between Russia and Ukraine involves pressure on Ukraine to recognise certain occupied territories, particularly Crimea, as Russian territory. What is your opinion on such a possible solution? What consequences could it lead to, and what should the international community focus on if this scenario unfolds?

If we leave the crime of aggression unpunished, we fail to break the cycle of impunity. The cycle which started with Crimea.

This would mean we are heading toward a new phase of war, potentially even more bloody than the current one, and one that might not be limited to Ukraine but could spread to other European countries.

In this context, Crimea is key because the current phase of the war – the full-scale invasion we are experiencing now, became possible precisely because the world did not react to what happened with Crimea in 2014 and to what continued in Donbas same year. Since there was no accountability, no punishment, and no halting of aggression, and since sanctions were not severe enough to cripple the Russian economy, Russia attacked a third time.

And now, unfortunately, we are at a point where this war might once again be frozen. And this is very bad news because the entire democratic world is about to repeat the same mistake. [If this happens] we should expect that the war will continue as soon as Russia is able to regroup, rebuild its military power, and attack again.

And, as we know, each new phase of Russian aggression has been even more brutal. For example, if we look at enforced disappearances, there were 43 documented cases in Crimea in the first years of occupation [2014]. In Donbas [later the same year], there were already hundreds and thousands of such cases. Now, the number of victims has risen to tens of thousands. We see that with every new phase of aggression, the scale of crimes multiplies exponentially.

This happens precisely because the aggression was not stopped earlier and because there was impunity. And now, unfortunately, we are again at a point where the same thing is happening. If we follow the logic of the first three phases of Russian aggression, then both Ukraine and Europe must prepare for the next round of an extremely bloody war — one that, having already gone through Crimea, Donbas, and all of Ukraine, will likely, in the next phase, expand beyond Ukraine.

What freezing the conflict means in practice?

“Freezing the conflict” means that the Russian Federation, which had planned to ‘take Kyiv in three days’, will adjust its strategy to calculate its next moves more carefully, making more realistic assessments of the capabilities of the countries it intends to attack.

It means that the Russian economy will remain highly militarised, even after this phase of the war’s active fighting subsides. Russia will continue to rebuild its military capabilities, which were damaged during this phase of the war.

It means that the militarisation of education in the occupied territories will continue, that children growing up there will be drafted into the army, will replenish the Russian military, and will become new soldiers for the next phase of the war.

For European countries, this means that the illusion of security is over, though some may still be clinging to it. There are serious internal threats to NATO, especially given the possibility that the United States may not honour its commitments and might refuse to intervene in the event of an attack on a NATO country or leave NATO at all.

This means that the European countries must take responsibility for their own security, increasing defence spending — possibly to 5% of GDP, even though many previously struggled with the 2% threshold.

It also means that many young people across Europe will have to undergo basic military training, learn how to shoot, operate drones, and adopt new battlefield technologies, also learn from Ukrainians. Unfortunately, this is a bleak prospect for our generation, but it is inevitable if we want to survive.

The recent decision by the US administration to suspend all foreign financial aid for a 90-day review has seriously affected the work of civil society. How does this decision affect Ukrainian human rights organisations and broader civil society?

It has already caused disruptions because many programmes have been halted. It’s important to note that when we talk about aid from the US government and the US federal budget, we’re not only referring to USAID but also to programmes directly funded by the US Department of State, as well as partially through other funds. In this context, civil society wasn’t the primary recipient of these funds because most of it went directly to the government [of Ukraine] for other programmes.

A significant portion of this aid was directed towards sectors like energy. The Russian Federation has been consistently attacking Ukraine’s infrastructure for years. This constitutes a war crime and a crime against humanity, as qualified by the International Criminal Court, which issued six arrest warrants related to this crime. It is very difficult for Ukrainians to survive winter after winter with prolonged power outages, often without electricity, heat, or water supply. A large part of US aid went to support the energy sector to ensure people had electricity and heat. Significant support also went to programs such as digitalisation, support for farming, veteran rehabilitation, psychological aid, and evacuation of people, especially those with reduced mobility, from frontline areas.

Naturally, the civil society organisations involved in this work were forced to suspend this aid, and it happened suddenly, overnight, which is critical for saving lives, especially for those in frontline areas.

Of course, a large portion [of US funding] was also related to human rights protection, democracy processes, and media support. The media sector has been one of the most affected by the suspension. The dependency of Ukrainian media on donors is understandable and obvious because, in the conditions of full-scale war, normal market models for media don’t function. For instance, the media cannot rely on advertising revenue. Ukrainian economic collapse in the first year of the full-scale invasion saw the economy shrink by nearly a third, and it is surviving in very tough conditions. Several hundred media [329] outlets, especially smaller regional ones, closed since the start of the full-scale invasion because they couldn’t survive. Often, this was due to economic reasons or because they were located on the frontline or in occupied territories. The surviving media outlets heavily relied on funds from the US federal budget.

When this funding is stopped, the question arises as to how many more media outlets will shut down. Of course, if we consider that Ukraine remains a democracy and is fighting a terrible war while maintaining a relatively high level of rights and freedoms within the country, the functioning of independent media is critical. Independent media uncover and highlight issues, including abuses and corruption within the army. If these media outlets are silenced, if we enter a freeze of the war and new elections, it’s scary to think about the absence of a powerful voice from independent media during these elections. Therefore, this has a very destructive, devastating impact.

The human rights organisations are affected as well, those helping victims of the war, documenting war crimes, and providing legal and psychological assistance. Some organisations that were heavily dependent on US funding have almost completely halted their work, such as regional legal aid networks or the ongoing documentation of war crimes. This is a significant blow to the work that aims to bring accountability for the most serious crimes committed during the war.

What steps can be taken to mitigate these consequences and ensure the continuation of international support for human rights activities in Ukraine?

We can see from certain publications that, as they say, “nature abhors a vacuum,” and China has already begun actively exploring the possibility of replacing some of the programs funded by USAID.

And of course, this presents a significant risk when an authoritarian country increases its influence worldwide, which is already considerable, for example, in the countries of Latin America, African continent, and also in attempting to enter democracies, using this influence for its own interests.

Therefore, it is crucial now to mobilise all donors who can support civil society, not only in Ukraine but also in other countries. Civil society in many countries has been affected.

The second important point in the design of financial support programs for civil society is that more attention should be paid to core funding, or institutional funding, rather than project-based funding. Given the changing and unpredictable external circumstances, organisations must have some funds that they can flexibly redirect to various needs, considering that sudden shifts may occur, such as changes in foreign policy, military contexts, or the suspension of other funding sources.

For example, if there were at least some institutional funding available within civil society organisations, the impact of a halt in funding, such as from USAID, would not be as devastating, because they could partially use funds from institutional or core funding to cover the most critical programs that need to continue. However, most organisations do not have such funding, and, of course, this has a devastating impact, not just on the organisations themselves but on their beneficiaries — the very people they work for and in the interests of.

Human Rights House Crimea member organisations are actively engaged in national and international advocacy. Please share which advocacy tools and strategies are currently being used at the international level? How effective are these efforts?

International mechanisms are in place and functioning; some new ones have been established. Regarding the situation in Ukraine, some of them have a general mandate, and we use them, but their effectiveness is very low. In the face of Realpolitik and the limited influence of some organisations like the United Nations or the OSCE, are incapable, through their tools, of stopping the bloodshed or holding the guilty parties accountable.

Even those mechanisms that are relatively stronger face erosion. We are witnessing a systemic failure, particularly with recent developments such as U.S. President Donald Trump’s executive order imposing sanctions on officials of the International Criminal Court, including Prosecutor Karim Khan. [And countries] that are failing to uphold their commitments. One example is Mongolia, which did not arrest Russian President Putin during his visit to the country.

Therefore, we have a choice: either not use these ineffective tools at all, which is probably not a very good strategy, or try to squeeze as much as possible out of the existing mechanisms and initiate new ones. We are following the second strategy regarding the situation in occupied Crimea.

There is attention at the UN General Assembly level, which annually adopts resolutions on the situation in Crimea. The UN Human Rights Committee is also active, as are Special Rapporteurs and other UN human rights monitoring bodies, which have been gathering, documenting, and reporting on events, crimes, and human rights violations over the years. Of course, these reports do not have an impact on the situation, but they are at least an independent and unbiased source of information for other UN member states about what is happening in Ukraine.

[The international community] has initiated and created new tools, such as the Independent Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine. Another tool employed in relation to the events in Ukraine is the OSCE Moscow Mechanism. New tools are also being created at the Council of Europe level, such as the Register of Damage, which collects and records information on the damage caused to Ukraine and its citizens due to Russian aggression. Efforts are ongoing to create a Special Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine. This particular crime is fundamental – because without Russia’s attack on Ukraine, none of the other crimes would have occurred. In the light of Crimea’s occupation it is worth mentioning the Crimea Platform, an international consultation and coordination format initiated by Ukraine in 2019 aimed at de-occupation of Crimea and its peaceful return to Ukraine.

It is crucial that these tools are being developed, and we must exert efforts to make international law work, against which Russia simply tramples. The international community cannot do anything about this. Unfortunately, yes, all these mechanisms are of low effectiveness in the short-term and to immediately stop violations. Perhaps some of them will yield results in the future, especially the International Criminal Court or the damage registry and compensation mechanism that should be implemented at the Council of Europe level.

But this often depends on political decisions, and political decisions depend on the situation on the battlefield and the endurance of the aggressor country’s economy. Therefore, the most effective approach to stop Russian aggression at the moment is, of course, the imposition of sectoral sanctions on the Russian Federation which should affect the entire Russian economy and undermine its ability to wage war on such a scale; and military and security assistance to Ukraine, so it can continue resisting Russian aggression.

To protect human rights, unfortunately, the most effective tool right now is weapons and the work of many servicemen, some of whom come from the human rights community—activists, journalists — who have joined the armed forces and, with weapons in hand, are stopping the advance of the ‘Russian world’, which in fact brings destruction, abductions, torture, and rape, essentially bringing the Middle Ages back to Europe. And this is the most effective tool right now.

Personal sanctions, in turn, are important to draw attention to specific victims, to the crimes committed against them, and to those responsible for those crimes. These sanctions will not stop the war, but in terms of calling out the wrongdoers, they are very important. It is vital that their names are mentioned, that they appear on these sanction lists, and that they understand they are being watched. We have been advocating for such sanction lists, and the latest development we expect is the European Union adopting new sanction lists regarding individuals working in the penal system of occupied Crimea and the Russian Federation, involved in the abuse, denial of proper medical care to Ukrainian political prisoners, etc. There should be better synchronization because, for example, some of these figures have already been included in the US sanctions lists for quite some time but not in the European ones. The goal is to reduce such inconsistencies and include more names of those human rights violators involved in abuses and crimes.

Letters to Free Crimea

It is crucial, especially in these difficult times and particularly for those [unjustly detained] in prisons in the Russian Federation and occupied territories, that these individuals know the fight for their freedom continues and that they have not been forgotten. This includes those who have been imprisoned even before 2022. We still have political prisoners, such as Valentin Vygivskyi and Viktor Shur, who have been incarcerated since 2014.

For the political prisoners who have been released, including those recently such as Leniie Umerova, Nariman Dzhelyal, Maksym Butkevych, and those released earlier, such as Oleh Sentsov, we know how important it was for them to feel that people had not forgotten them and were fighting for their release. It is also crucial for them to receive letters. Therefore, this informational pressure is vital. The fact that this issue, the fate of these people, remains on the agenda, that the media report on them, that people write about them on social media, and send letters — this is what helps them endure everything, not break, and ultimately survive until their release.

We have been running a continuous campaign, Letters to a Free Crimea, in cooperation with the Mission of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and PEN Ukraine. We collect letters for Crimean political prisoners and then pass them on through relatives and lawyers. It’s possible to send letters via mail from European countries, but not from Ukraine as they do not reach [Russian detention centres].

Read more: Kremlin Prisoners: How to write a letter to a political prisoner

The name of the campaign is symbolic. [We consider those Ukrainians in Russian detention] to be in double imprisonment: being behind bars and being detained on the occupied territory or transferred to the aggressor country detention centres or colonies.

Despite the total external lack of freedom, the person in their thoughts remains free. And it is important that messages from Ukraine, the world, and concerned individuals reach this “Free Crimea,” which is currently doubly imprisoned.