Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF): When did you first become interested in human rights, and why did you decide to become a human rights defender?

Intigam Aliyev (IA): After Azerbaijan gained independence, there were high hopes for democratisation. Sadly, it was not to be.

Former Soviet KGB General Heydar Aliyev came to power once more in the early 1990s – he was the leader of Soviet Azerbaijan for two decades prior – and the process of democratisation was suspended and the country gradually slid towards the same authoritarian rule that for many years turned the USSR into a prison of nations.

With the advent Heydar Aliyev’s power – later inherited by his son, Ilham Aliyev – gradually, the persecution of dissidents, arrests of journalists, and political, civil and other activists became a reality of life.

Then I made a decision: I will be among those who fight against the dictatorship. And so it has been for more than 30 years.

HRHF: What work were you doing prior to your arrest? What did the authorities accuse you of doing?

IA: I specialise in the protection of fundamental rights. I have submitted more than 200 complaints to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) related to violations of the freedoms of expression, association, as well as elections, protection from torture and more.

Prior to my work with ECtHR and in addition to my educational and domestic litigation work, I was actively involved in international advocacy and cooperated with many European and international NGOs and inter-governmental organisations, such as the Council of Europe, the United Nations, the OSCE. I have served as a human rights expert on various platforms, such as the CoE Expert Council of NGO Law or the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum.

I was arrested in August 2014 as part of a joint criminal case initiated by the General Prosecutor’s Office of Azerbaijan in April 2014 against a number of domestic and international NGOs on the grounds of alleged “irregularities found in the activities of a number of NGOs, and branches or representative offices of foreign NGOs”.

On April 2015, I was sentenced to seven and a half years of imprisonment. I was convicted under trumped-up charges of illegal entrepreneurship, tax evasion and other charges, all related to grants received from various donors for human rights activities as the prosecution claimed that I failed to register grants with the Ministry of Justice – that was also a lie.

This was part of a broader and more systemic crackdown on civil society that has been going on for many years. The repression reached its peak between 2013 and 2015 when many NGOs, working in the field of human rights have been targeted by criminal cases; their leaders and activists were arrested on trumped-up charges, and dozens of civil society leaders were forced to flee the country to avoid prosecution. Many international organizations including Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Open Society Institute (OCİ), ABA ROLI, and international media such as Radio Liberty, BBC and others were expelled from the country. Some of them were also targeted in the criminal case in 2014, which remain in force to this day; criminal cases against human rights NGOs also continue.

I remained in jail for nearly two years before being released on probation and banned from leaving the country for five years. The prosecutor’s office illegally kept seized documents and equipment for 5 years. This continued even after my release and they were returned only in 2019, and not everything, and some of the equipment was broken.

I was recognised as a prisoner of conscience by international human rights watchdogs, including Amnesty International. Thanks to the efforts of the international community, I was released alongside some of my civil society colleagues.

Many more political prisoners remain in the country: more than a hundred critics and opponents of the authoritarian regime – journalists, politicians, human rights activists, etc. Unfortunately, not many of them have a chance, as it was in our case, to be released early from prison and to be rehabilitated.

HRHF: Did you ever consider that you could actually end up in prison for your human rights activities at the time?

IA: Unfortunately, in the 21st century, there are still countries where human rights are perceived as something harmful, evil, and human rights defenders are seen as dangerous and are being persecuted, arrested and killed. It is regretful that the situation in my country continues to raise concerns.

In April 2014, the authorities opened a criminal case against some human rights NGOs, my organisation LES was among them. At that point, it was clear that these criminal cases would be followed by arrests. I was among the potential candidates to be sent to jail.

It was easy to predict: in speeches by high-ranking officials of the state and in numerous articles in the media controlled by the authorities, I was accused of “anti-state” activities (similar accusations were made against other activists critical of the authorities).

In June, I had a trip outside the country. For some reason, the authorities allowed me to leave, maybe they really wanted me not to come back.

During this time, in Prague, I was invited to Radio Liberty and they asked me “Will you return to Azerbaijan despite the risks?” I replied that I would definitely return and shortly after I did, I was arrested.

HRHF: Why did you continue your human rights work despite the risks? Would you make the same decision today?

IA: Do I regret it? In prison, when I was sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly intimidated… that if I did not give up the cases I was conducting in the European Court, I would be in prison for a long time, perhaps I might not get out of there alive.

What happened to me in prison showed how serious these threats were. But, even in the most difficult times, it never occurred to me that I could back down. I would lose respect for myself. This is the worst thing that could happen to me.

Then, the authorities began to persuade -” be silent in court, it will be better”. I refused. In speeches at the trial, I repeated the same things I said before my arrest. All this ended with the prosecutor demanding 10 years in prison for me.

In my closing remarks in court, I repeated once again what I said during the entire period of my arrest: I do not regret in the slightest that I was engaged in human rights work; if I’m lucky and get out, I’ll continue what I did before my arrest.

When I was released, as promised, I continue. Despite all the difficulties – health problems, obstacles, risks. Many more people, both in my country and elsewhere, are imprisoned for their beliefs. They need our support.

HRHF: Can you describe what life is like as a political prisoner (in Azerbaijan)? How does it feel to be behind bars unjustly? What is an ordinary day in prison like?

When you are deprived of your freedom, no matter where it happens – in America, Norway, France, Turkmenistan or Azerbaijan, it is of course accompanied by suffering. Prison is prison everywhere. But when you are punished, not for some crime you have committed, but for your work, your thoughts – it hurts more.

IA: But you prepare yourself for all of this for a long time. You know that at any moment you can be arrested, and you can somehow endure it more calmly.

For various reasons, much of what happens there is usually not made public. It is very difficult when you are deprived not only of the opportunity to write letters, but to do what you love (it was forbidden to help others in their legal cases), access to newspapers, communication with relatives, and friends, and sometimes even with people with whom you are in the same space, to play sports, but also to engage in training, creativity, scientific research, journalism, literature.

Books are allowed with the exception of some – with “doubtful content”, but writing articles for the media, a diary, stories, or a novel is not. One of the prisoners from the cell would immediately inform the prison authorities and the guards would come and confiscate. Of course, all this is done illegally…

When the prison guards once again confiscated a letter that I was writing to friends, I asked them a question: “Can I write love letters?” They looked at me to see if I was being serious or sarcastic. I presented a very stern look. Then one of them answered categorically: “It is impossible!” I asked: Why not? He looked at me almost reproachfully and answered: “Because you are a married man!”

I would like to especially note: not all of my experience with prison is bad. I also got to know this part of life closely, the hardships and tragedies of the people who are there. Among them, there are a lot of innocent, so-called victims of the corrupt and dependent on the authorities system of law enforcement and judicial bodies.

Unlike political prisoners, many of them have no chance of getting justice. This situation is reflected in the novels that I wrote after my release from prison: The Square (2016-2017) and Death of a Scoundrel (2018-2019).

In this sense, I am grateful to the authorities for letting me get to know prison life well. If the authorities had not sent me to prison, my novels would not exist.

They are also posted on several local well-known literary sites and are the most-read books in recent years (about 100,000 people had access to the links). These are very high rates in a small country like Azerbaijan.

HRHF: How important was solidarity for you? Did you ever feel hopeless in that situation? What kind of toll does it take on a person? How were you able to endure?

IA: I won’t lie. In prison, there are often very difficult, sometimes even seemingly hopeless, situations. But when you think about the terms of some others – Nelson Mandela spent 27 years in prison – when you think about the terrible conditions they were kept in, you have to stay on your feet and hold your head up.

At that time, many of my friends and colleagues were in prison, including well-known human rights defenders and civil society activists Anar Mammadli, Rasul Jafar, Khadija Ismail, Leyla Yunus and others. They bravely held out.

International attention and support for people who work in the human rights field is very important for them, and above all in a moral sense. When I was in prison, I received many letters of support, postcards from all over the world. In prison, I was elected a member of the CoE Expert Council of NGO Law. While in prison, I was awarded many prestigious human rights awards.

We were supported by the progressive part of our society. Our release was demanded by many international organisations, the governments of many democratic countries. Ordinary people all over the world raised their voices for our freedom. There have been many campaigns for our freedom. Our families supported us. All this gave strength.

HRHF: Why did you decide to stay in Azerbaijan following your release? Did you think about moving abroad for safety?

IA: As I indicated earlier, I had the opportunity not to go to prison in 2014.

For people that would prefer to seek shelter, there is usually a fairly large selection of countries. I preferred jail. And after release, I must stay – despite the difficulties.

This is our country and we want to be free.

I never thought of leaving Azerbaijan, although I am sympathetic to those who were forced to take this step; among them, there are many people who are doing very useful work for the country.

HRHF: What is the situation for HRDs in Azerbaijan today?

There is no longer a vibrant civil society in Azerbaijan as there was ten years ago.

IA: In the past, the Legal Education Society and other organisations were able to implement numerous human rights activities. We conducted numerous campaigns domestically and internationally against human rights violations and demanded an end to political prosecutions. All of this is now missing: the independent NGO sector is actually out of order; as well as other institutions of civil society – independent media and advocacy, opposition parties, etc. And the presence of political prisoners, moreover in such a large number, is an indicator of the absence of an independent judicial system in the country.

Despite the calls from international organisations such as the Council of Europe, the EU and the UN, there remains restrictive legislation and a repressive political environment for civil society activities in the field of human rights and the rule of law. Engaging in such important activities for society carries political risks.

Unfortunately, many international organisations that supported independent local NGOs were forced to suspend their activities in 2014. Some of them were prosecuted. Also, because of unbearable working conditions, the Baku Office of the OSCE suspended its activities.

LES was one of the strongest NGOs not only in our country. The projects implemented by LES covered areas such as raising legal awareness, strategic litigation and supporting lawyers involved in strategic litigation, preparation of reports related to different human rights issues, drafting complaints to the ECtHR and communications to the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, organisation of training for lawyers, human rights defenders, young activists, journalists and etc.

Prior to closing, LES was a member of a number of international platforms and networks, such as EaP Civil Society Forum of the European Commission, the South Caucasus Network of Human Rights Defenders and the Network of Human Rights Houses.

My organisation actually does not exist now. Its activities are banned, its bank accounts are closed, the criminal case against LES is not closed… Many other NGOs are in the same situation.

At the beginning of June 2023, information spread that the authorities had dropped criminal cases initiated in 2014 against some NGOs. But the criminal case against the LES has not been terminated. From 2014 to 2019, the organisation’s office was illegally sealed by the prosecutor’s office and access there was denied throughout this period. The bank accounts of LES to this day illegally remain frozen. The ECtHR has recognised the freezing of the bank accounts of many human rights organisations and their leaders by the national authorities as a violation (Imranova and others v. Azerbaijan, judgment of 16 February 2023; among them was me and my organisation).

But, despite the difficulties, the work does not stop. Many young people are coming to the civil sector – smart, creative and committed to the values of human rights. It is reassuring and empowering.

History has repeatedly proven that a departure from the values of democracy and human rights, no matter the good intentions, will sooner or later return to us in the form of wars, extremism, corruption, poverty and the disruption of international order.

By the way, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, which oversees the execution of the decisions of ECtHR is not satisfied with the work of Azerbaijan’s authorities and the work carried out by them in this direction. The Committee of Ministers has urged the authorities to take real measures aimed at creating normal conditions for the work of NGOs (the adoption of both legislative and practical measures).

HRHF: What is the situation for you now personally? What threats do you face as you continue your work as a HRD?

IA: I was banned from leaving the country for 5 years. The use of arbitrary travel bans has become in recent years a standard tool for harassing human rights defenders, independent journalists, and opposition activists in Azerbaijan. I was on the list of people the authorities bugged through the Pegasus spyware.

Since 2004, I have been illegally deprived of the status of a lawyer; in 2018, the ECtHR found that I was denied admission to the Azerbaijan Bar Association (ABA) in relation to my views and criticism in my professional capacity (Hajibeyli and Aliyev v Azerbaijan, judgment of 19 April 2018). But the authorities refuse to comply with the decision of the ECtHR.

Now I, and others blacklisted by the authorities and the pro-government ABA, can only pursue cases in the ECtHR. Since 2017, I and many other lawyers, who are not admitted to the ABA, or illegally excluded from it, cannot participate in any court cases at the national level (before that, non-members could act as a representative in civil and administrative courts), which creates very serious problems with bringing cases to the ECtHR.

The authorities also refuse to comply with the decision of the ECtHR on my rehabilitation.

In Aliyev v Azerbaijan, (judgment of 20 September 2018) the ECtHR found that the freezing of assets of NGOs was part of a general tendency of repressing the freedom of association and professional activities, especially of lawyers representing clients before the Court

The Court found that there has been no basis for such charges in the domestic law, nor any evidence to arrest me. It also found that my arrest and detention were aimed to punish me for my human rights work and also ruled that the Government of Azerbaijan misuses criminal law to prosecute and arbitrarily detain its critics.

My trial was conducted in the same manner, in the absence of any credible evidence, and the domestic courts often repeated the text of the prosecution in their decisions word by word. In the same judgment, the Court has ordered the Government to take measures aimed to restore my professional activities.

Since the criminal case against LES has not yet been terminated and all that implies, I have to work from home. Much of what I do, I do on a voluntary basis. I could do much more than I can do now. The authorities do not give me that opportunity.

I am, however, not complaining.

HRHF: Many of our colleagues in Belarus are behind bars for their human rights work. If you could speak to them directly, what message would you have for them?

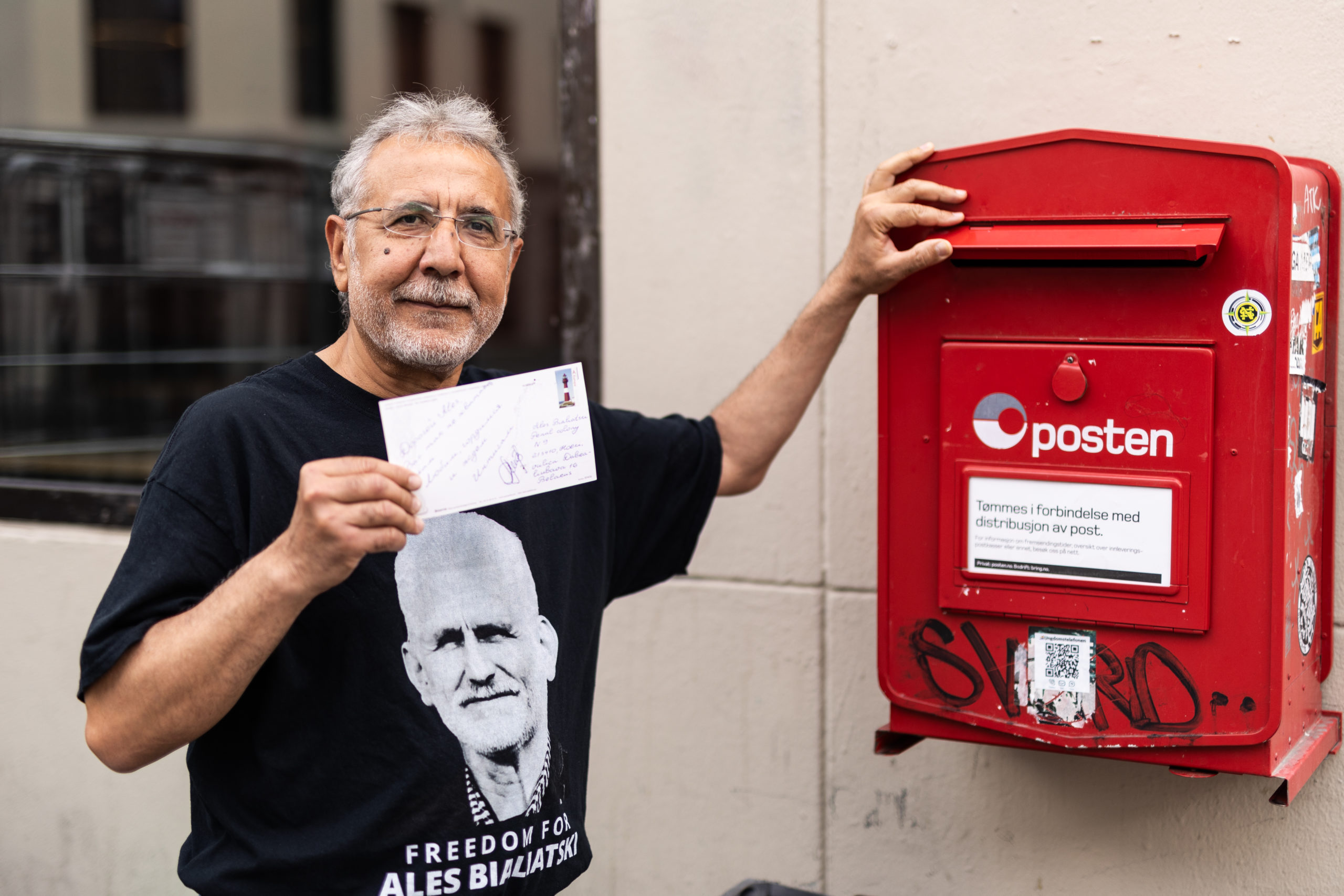

When Ales Bialiatski was arrested in 2011, I wore a shirt with his photo in various campaigns for his release. When he was released and a little later I was arrested, then Ales was already putting on a shirt with my photo. Now, when Ales was arrested again, I had once again put on the same shirt with his photograph.

Ales [Bialiatski], Uladzimir [Labkovich], Valiantsin [Stefanovich] and other Belarusian human rights defenders and activists are in prison, so that our children never have to wear these shirts bearing the photos of their friends, relatives and like-minded people.

If I had the opportunity to talk to them, I would say to them: We are proud of you, admire your courage, love you and hope to see you in freedom very soon.

HRHF: What can people do to support political prisoners?

IA: To be realistic, citizens in Norway, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, etc. are unlikely to influence human rights policies and the situation for political prisoners in authoritarian countries.

When powerful states and powerful international organisations cannot force the dictator of a small country like Belarus to release even a Nobel prize-winner, what can be expected from ordinary people?

Ordinary people can, however, do some important things. These things might appear, at first, very simple, but they are very necessary for those in prison. They can give them strength and energy.

Although some may object: citizens can demand from their governments a more principled approach to human rights issues, not only in their own country but in other countries too.

Do not vote for politicians who are on good terms with dictators; even on such intimate terms, that they enter into corrupt ties with these governments. As was the case with some politicians from Spain, Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom in the Council of Europe or the European Union.

I recently read a letter from one of the Belarusian activists who has been in prison for several years. Valiantsin Stefanovich: “I’m always waiting for letters. It’s only books and letters that keep me going. Everything else here is the same, nothing interesting. The usual jail routine.” It’s sad to read this. I understand Valiantsin very well, I myself experienced the same feelings in prison.

The most important thing for a political prisoner is to know they are remembered. The letters, postcards, birthday wishes, books made about them… and their families seeing the faces on the shirts… it means a lot to us.

HRHF: Authoritarian states often seek to defame human rights defenders and portray them as unpatriotic, enemies of society, “foreign agents”, and so on. What is your view on this narrative?

IA: Usually, the stigmatic use of “enemy”, “agent”, “unpatriotic”, “corrupt” and the like are used in relation to those who are not bribed. It’s not pleasant, but you get used to it and continue to do your job.

When human rights activists, journalists, and civil society activists are called foreign agents, not patriots of their country, corrupt, etc., it means this is an authoritarian government.

Human rights defenders play an important role in promoting human rights, democracy and the rule of law. They take upon themselves the protection of persons whose rights have been violated, help them to defend their violated rights in local and international courts, together with other civil society institutions, achieve the accountability of the authorities, the compliance of a State’s international obligations, conduct various campaigns and much more.

In carrying out their mission, especially in authoritarian countries, human rights defenders often face numerous obstacles and are subjected to illegal detentions, criminal prosecution, smear campaigns, threats and intimidation, abuse, illegal surveillance, etc. There are many cases when human rights defenders have been killed, or terribly injured. And often these crimes are not investigated effectively, as they are committed with the blessing of the authorities. All this leads to impunity for the perpetrators and continued persecution of human rights defenders.

HRHF: What is the value of international solidarity from partners in the Network of Human Rights Houses?

The strength of the Network of Human Rights Houses and their partners lies in their commitment to the values of human rights.

IA: The Network of Human Rights Houses and their partners do not adjust their activities within the framework drawn by authoritarian authorities.

They do not try to please them, do not try to find a common language with dictators for the sake of projects. They are not afraid to work with people and organisations that the authorities are slandering.

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Human Rights House Foundation and its partners for the support they have always given to the civil society of our countries and political prisoners.

About Intigam Aliyev

Intigam Aliyev is a prominent human rights lawyer. He has been actively engaged in challenging human rights violations in Azerbaijan for more than two decades and his work as an attorney, educator, and lecturer exemplifies the skills, determination, and bravery required to create meaningful change. He is the founder of Legal Education Society, a member organisation of Human Rights House Azerbaijan.

Intigam Aliyev has faced serious consequences for his endeavours, including imprisonment and politically motivated judicial persecution. Nevertheless, he remains courageous and indispensable in promoting human rights in Azerbaijan.

For decades, Intigam Aliyev has litigated human rights cases, including on freedom of expression, association, assembly, elections, torture, and more. He has brought more than 200 cases before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). ECtHR found violations in over 100 of these cases. He is the author of over 20 books and over 100 academic articles.

Intigam Aliyev has served as an expert and local partner of a number of international inter-governmental and non-governmental organisations (CoE, OSCE, UN, NED, ABA ROLI, GIZ/GTZ and etc.) As an educator, he has trained a new generation of human rights lawyers, activists and human rights defenders in the country

While still in prison, Intigam Aliyev was selected as a member of the Expert Group of the Council of Europe on NGO Legislation.

For his work in uncovering large-scale systemic human rights violations, Intigam Aliyev has been recognised by several human rights awards including: the Norwegian Helsinki Committee’s Andrei Sakharov Freedom Award (2014), People in Need’s Homo Hominy Award (2012), International Bar Association’s Human Rights Award (2015), Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe’s (CCBE) Human Rights Award (2015), Civil Rights Defenders’ Defender of the Year Award (2015), Global Network for Public Interest Law/PILnet Foundation’s Publico Award (2016) and more.

After being released from prison, where he spent one year and eight months (2014-2016), Intigam Aliyev wrote two novels – “Square” (2016-2017) and “Death of a Scoundrel” (2018-2019).