On the Anniversary of the protests sparked by the disaster at Novi Sad

It has been one year since the protests triggered by the Novi Sad station collapse, which killed 16 people and seriously injured one more. What is the current state of the student movement that emerged from the disaster?

The student movement has evolved significantly since the end of November last year. What began as a spontaneous call for justice and accountability over the tragic loss and killing of the people under the fall of the train station canopy has matured into a broader social movement.

The demands of the movement have changed over this period, and they have adapted as the situation has developed, depending on the response from the government–or the lack thereof.

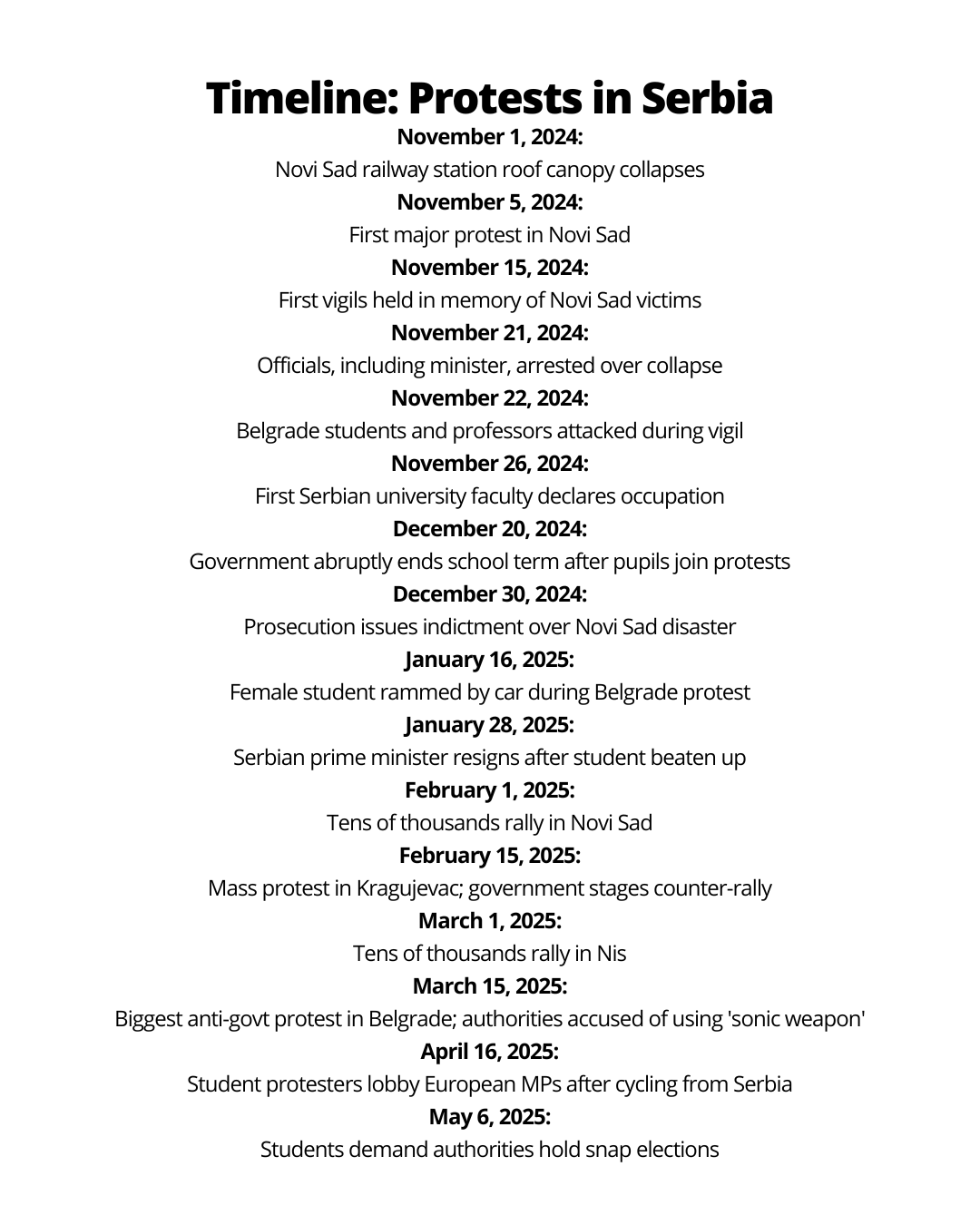

On 1 November 2024, the concrete canopy at Novi Sad railway station collapsed, killing 16 people and injuring several others. The protests that erupted following this incident quickly grew into a nationwide movement initially demanding accountability and an end to corruption. Since then, peaceful demonstrations have been met with increasing force, and the protesters have demanded new snap elections.

As of June this year, the Students have compiled all their demands into a request for elections because they realised that without at least partly free elections, and the possibility of a change of government, there is no way that they can actually reach the level of accountability that they are calling for.

One thing that has not changed is the organisation of the movement. There is still no leadership by design, and I must note that this style is unusual for this region. But, against all odds, it’s actually working, and the students are reaching people.

The reason the student movement remains leaderless is that this is the easiest way for them to avoid being attacked by the government, which would very much like the movement to be silenced.

Some have compared these protests with the Otpor protests of the late 1990s/early 2000s, leading to the ousting of Milošević. Do you have any thoughts on this comparison?

They have both been revolutionary, but I wouldn’t say they are similar, because the Otpor movement happened in a different era–it was a post-war movement.

The Otpor movement was a joint movement including students, activists and the opposition, fighting the criminal regime of Slobodan Milošević. It was an inevitable movement because no one was free in society at that time.

The student movement in Serbia today has, in a way, an even bigger task because the situation is so different. Mobilising people is harder than back then.

Serbians have enjoyed a degree of democracy since the 2000s, which is a success of the Otpor movement. And as a result, people today do not have the same huge existential problems that were faced back then–with the exception, of course, of socially vulnerable groups. Although there is a lot of underrepresentation in the country, it’s hard to mobilise half of the population to actually participate in this kind of revolutionary action.

But today’s social movement is extremely important, and it’s actually waking up people who were not very interested in politics and who are now becoming very aware that everything is political. It seems like people are realising just now, after more than 30 years of multiparty system reinstalment, that if they want to have the liberties and services that they are paying for with their paycheques, they actually need a responsible political option in power.

Can you give an overview of when excessive force against protesters began?

In the first five months since the protests began, the government didn’t know how to respond, and their strategy changed every few weeks.

At first, the government tried to be friendly and appeal to the students. They offered very cheap apartments for youth, talked of better pensions… etc.

So this was the first approach to dealing with the movement, but it didn’t work, and then the government became more vocally derisive and critical of the students. But it was, at least, peaceful until 15 March, which marked the change in the government’s response to the protests.

15 March was the protest when the sonic device was used against peaceful protesters.

Together with five other CSOs, YUCOM collected testimonies from the people affected. And since people had never experienced this kind of attack before, everyone realised that they were not alone and that this was an organised attack against them, citizens peacefully exercising their freedoms of assembly and expression.

And since this caused a lot of international attention, as well as attention inside Serbia, the pressure mounted on the government to make a response.

Initially, the government emphatically denied possession of any such device, then, after a few days, they admitted that they indeed had such a device in an attempt to say “yes, we have the device, but it’s not capable of this kind of action”.

If not the device, then how does the government explain the now-famous video footage of protesters dispersing? According to the president, it was orchestrated and choreographed–standard practice within a colour revolution.

At that moment, we realised that not only do the authorities actually have this sort of device, but perhaps they don’t properly know how to use it. Either they used it with intention against people, or they let someone who is not trained use it. In either scenario, someone must be held accountable, and the device appears to be in the possession of the police force.

Organisations that collected the testimonies initiated a case before the European Court for Human Rights (ECHR), and it’s ongoing.

After that, the governmental repression really escalated from the 28th of June, when there were protests in Belgrade. That was the first time we had a huge clash between the police and protesters, and a lot of people were beaten, media representatives were attacked. There was a lot of unlawful use of force. This pattern of repression continued with every subsequent large protest.

In HRHF’s Spring coverage, your colleague Uroš Jovanović noted that the student movement had consciously distanced itself from civil society. Has this changed?

The distance remains as a safety measure, but in practice, there are some developments. When the student movement first set its rules, it was to protect itself from attacks. Originally, they had no leaders and a very loose structure. This was to avoid the stigma that civil society faces. They distanced themselves from the opposition, civil society, and any organised party or movement, though individuals from anywhere were welcome to join the protests. That approach made sense at the start of the protests.

After a year, that principle remains. I believe that by now, they’ve begun to recognise which part of the civil society is legitimate and with expertise. To answer the question clearly, there is no formal cooperation between the CSOs and the student movement, but they do rely on legitimate CSO research or findings.

You mentioned the stigma that civil society faces. Can you elaborate on that?

Civil society in Serbia faces enormous stigma because the propaganda machine from the 1990s was never switched off.

Civil society is broadly perceived as “foreign mercenaries or traitors” of the Serbian nation. This propaganda was targeting mainly those working on war crimes and dealing with the past during the ‘90s, and that remained a widespread perception, since no Government was very eager to remove this stigma. So the result is that the CSOs today are still massively portrayed as those against the Serbian people and society, which is clearly far from the truth.

Considering that, civil society does not enjoy much trust by the broader public, but I tend to think this is changing — and it’s been changing rapidly, since 15 March [the alleged use of a sonic weapon for crowd control]. What motivates us as civil society now is that we see potential for change, and we see greater interest from the public in our work.

Why do you do this work despite the risks and stigma? What motivates you?

As a student, I thought that I wanted to work within diplomacy, but I realised that the work of civil society is exactly where my heart was. You put your knowledge toward the values you believe in so that everyone can have equal access to the law and services that this country should have.

Civil society is accused of serving foreign interests, but our only interest is to serve people in Serbia, to recognise and respond to their needs. And even if citizens don’t understand it that way, we work for them.

For our organisation YUCOM, for example, our primary role is to provide free legal aid to citizens. We can do that only if we work in a good legal framework and if we have functioning institutions in Serbia, which are both very questionable lately. But we work within the framework of the Serbian constitution, where the rights of the citizens are guaranteed. The problem is that this is not applied to every citizen of Serbia equally, so we strive to change that.

Civil-Society Space & Human-Rights Defenders

How would you characterise the current environment for civil society and human-rights defenders in Serbia? What are the new pressures or persecution patterns you are seeing that might not have existed a year ago?

The situation now is quite different from last year, and it continues to deteriorate. Attacks on civil society have always existed, but since, perhaps 2020, they’ve worsened. We track them in our “map of incidents,” and early on, most attacks were smear campaigns, different kinds of smear campaigns from various politicians targeting critical voices from civil society. Then came the infamous list of 104 CSOs and individuals investigated by the Administration for the Prevention of Money Laundering. We warned the public that this was happening, and the investigations ultimately went nowhere, because of the strong international reactions of the misuse of the anti-money laundering legislation in this way.

With the rise of the environmental protests in Serbia (2020–2023), misdemeanour charges began to rise as part of the strategy of the authorities, intimidating “informative talks,” and accusations of “undermining the constitutional order.” The criminal charges didn’t go through, but they were meant to intimidate. Many plea agreements were signed, which was precisely the deterrence tactic.

Meanwhile, we had this “dialogue” with civil society with regards to the EU integration process, because the authorities are obliged to have civil society at the table. Government representatives would sit there pretending to be nice, while at the same time, environmental activists were being arrested, or these misdemeanour charges were being issued, and smear campaigns against civil society were running in the tabloids.

Things escalated, and in late 2023, we got reason to believe that the government was using spyware to monitor civil society. In 2024, Amnesty International’s Digital Prison report revealed that this spyware had been planted on activists’ phones while they were detained in police custody, likely by the secret service. Again, Serbian CSOs, including YUCOM, filed criminal charges, but nothing has moved. A case was also opened by the Ombudsman, but this is also not going anywhere, since this institution is also one of the captured ones.

In February, armed police raided five NGOs — allegedly over USAID funds — they sent twenty armed policemen into the premises of five organisations, including our neighbours Civic Initiatives, also a member of Human Rights House Belgrade. They took a lot of documentation, but a formal investigation was never opened. Despite that, the president publicly referred to the seizure of these documents as a “pre-investigation.”

So this is the environment that we’re working in. Just a few days ago, Human Rights House Belgrade was vandalised with graffiti calling us Ustaše, something they like to call us to paint us as being anti-Serbian, and “blokaderi”, a term for the student blockades.

After the February incidents and the relentless smear campaigns, we, the civil society gathered in the National Convention on EU (the official platform for civil society cooperation on EU integration), withdrew from all high level official cooperation with the government, and most of the CSOs withdrew from the government’s working groups.

For years, we’ve had this situation where the government slaps you with one hand and offers candy with the other. Now we’ve stopped playing along, since nothing we said at those tables was ever taken seriously.

What do you identify as the major risks or threats to the student movement – and to Serbian civil society more broadly – in the upcoming months?

It depends a lot on what happens in November. We’ve seen how previous large protests went — 28 June, the protest throughout August and September — with police openly attacking peaceful protesters. If that repeats, I think we’ll be entering the final stage of the government’s repression.

How that will look depends on their external goals and how the EU continues to deal with them. The EU’s tone has shifted slightly — they’re now addressing messages more to the Serbian people than saying that the government is actually what Serbia represents to them. A lot depends on whether Vučić will keep trying to pursue EU membership or will abandon it. But the EU has been useful for him, they used mechanisms from the EU integration to misuse EU funds. This is also part of Laura Kövesi’s investigation into misuse of EU funds for railway projects.

I’m not an expert in these kinds of scenarios, but if November turns violent — used as a pretext for police brutality — I think it will show where the government stands. There’s uncertainty: at the 1 October assembly, there was almost no police presence, even after the violence in September. Still, the government’s current rhetoric, “expecting violence” is a clear warning sign — for us, that means they’re preparing to create it.

International Attention & Advocacy

What role do international actors — EU institutions, UN mechanisms, and the Council of Europe — currently play in supporting civic space and human rights in Serbia?

Since December last year, we’ve had more communication with UN mechanisms than ever before. Serbia has drawn unusual attention from UN special procedures — including the Special Rapporteurs on human rights defenders, freedom of assembly and association, freedom of expression, torture, and judicial independence, as well as on education. There were six or seven official communications to the government, and two requests for country visits. The government acknowledged them but never set dates, so those visits won’t happen this year.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights also offered an independent investigation into the sonic device case — again, no response. Meanwhile, the European Court of Human Rights issued interim measures that led to a full case, and both the Council of Europe and the European Parliament rapporteurs reacted. The new European Parliament resolution on Serbia is particularly firm and detailed. I’d also say the new EU enlargement Commissioner is far more attentive to civil society and activist concerns than his predecessor.

A year ago, your colleagues (Dragoslava Barzut, Public Policy Program Manager, and Alma Mustajbašić, Researcher, Civic Initiatives) spoke about the lack of international attention to developments in Serbia, despite the EU’s obligations to monitor candidate countries. From your perspective in 2025, has this changed?

I see these as important symbolic gestures. The chances of the students winning the Sakharov Prize were never going to be too high compared to other awards, but I think it was a very good symbolic gesture to show the students that there is someone in the EU who actually thinks that what they did is highly appreciated in the course of fighting for freedom and democracy.

“You have cycled 1500 km from Serbia to Strasbourg and to @coe – what a powerful testament of dedication to the values of democracy! Our core mission is to defend and strengthen democracy, with a focus on empowering young people at the heart of it” @CoE_Education @ACoY_CoE… pic.twitter.com/7XSAlKhaOM

— Bjørn Berge (@DSGBjornBerge) April 16, 2025

It’s the same with their Nobel Prize candidacy: it’s not about winning, but about recognition. The gesture also mirrors their own symbolism — biking to Strasbourg and running to Brussels — presenting their case in the heart of the EU, not necessarily going into whether they are pro‑EU or not, but simply young people making a stand for democratic values.

International awareness of Serbia’s situation has grown noticeably since April or May and is now peaking, with the issue reaching the European Parliament. We’ll see how the institutions respond, but it’s already a major topic. We’ve spent months alerting international bodies, and now, after six months, we’re finally seeing stronger engagement and concrete recommendations on how the government should act.

How can international actors support the pro-democratic population in Serbia?

First of all, the approaches have to change. International actors need to stop addressing only the government of Serbia and start addressing certain messages to the Serbian people. This is so important because now is the moment when these actors are being watched by our citizens.

The second thing would definitely be continuing to invest in democratic forces — whether it would be civil society, or in the political sphere, the pro‑democracy opposition representatives who want to provide democratic solutions for the country, and of course, investing in the student movement.

And by investing, I don’t only mean money. Training, mobilisation meetings, building trust and partnership or whatever can actually help them reach as many people as possible with their messages. This is the minimum that needs to be done, and there is no better time then now.

Jovana Spremo

Jovana Spremo, Advocacy Director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Human Rights, manages the advocacy activities of the organization, with special focus on independence of judiciary and human rights. She holds a BA in International Relations from the Faculty of Political Science of the University of Belgrade, MA in the interdisciplinary programme of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Law and LLM in European Integration at the Law Faculty of the University of Belgrade. She is the coordinator of the Working Group for Chapter 23 of the National Convention on European Union.

Her expertise is in the domain of rule of law, with a special focus on the EU negotiation process, covering topics related to judiciary, protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms, as well as transitional justice and reconciliation. Jovana is the European Young Leader, class 2024, and an alumna of several international and regional programmes, including the OSCE Dialogue Academy of Young Women and Reporting on Genocide and Mass Violence Programme organized by the International Nuremberg Principles Academy.

Top photograph: protesti.pics