It has been six months since you were released. Why did you decide to leave Belarus? How has your life changed in this time?

When you come out [of prison], it’s like being a fish washed up on shore. It’s tough – in the first few days I couldn’t even pick up my phone or read something on the computer, it was psychologically challenging.

Even on the day of my release, I had no plans to emigrate, to flee the country… I had been saying the same even before my arrest in 2020: “Let [the Lukashenka regime] leave… I haven’t committed any crime”… On the 11th day after my release [2023], I made a difficult decision for myself. I had to leave the country.

After my release, I found out that my personal information had been added to the government-approved list of extremists – so there was increased attention towards me.

I had to notify and ask for permission even to leave the city, not just the country. I was monitored with a video recorder twice a day – at any time, police officers could appear at my doorstep… They would turn on the video recorder and have me sign a paper stating that I was at my place of residence, and they even said they could come at night, despite the fact that I have a young child.

Once a week, usually on Sundays, I had to report to the criminal executive inspection for so-called “preventive measures”, like watching a movie about drug addicts for one and a half hours. I signed my attendance and was free to go. And on the same evening, they would return with the video recorder, checking again. Every financial transaction was monitored – even if I topped up my mobile phone balance by one ruble. In such conditions, I would have to live for a period of up to seven years.

It felt like I had moved from one prison to another. I realised that it would be difficult for me to survive under these circumstances, even for a few years.

Andrei Strizhak from BYSOL told me, “You’d be better off leaving. It just so happens that you are now the most prominent [free] human rights defender in the country, and they won’t leave you alone.”

I understood that I wouldn’t make it through another sentence. I know what I’m talking about, I know what the conditions are like – and the medical care. A new term for me would have been a one-way ticket.

How does it feel not to be able to come back to Belarus because it is not safe? What do you miss the most about Belarus?

The most oppressive feeling is to live without knowing when you can return to Belarus. I never planned to emigrate. Everything I have is in Belarus.

Right now, I am in relative safety. Lithuania is a free country, and I thank the Lithuanian government for granting me such asylum… But I want to live in Belarus, it’s my home. And they took my home away from me.

My family is still in Homieĺ – my wife and our school-age son. I am deprived of the opportunity to raise my son, live with my family, deprived of the opportunity to live in my own country – that’s also a punishment.

During my son’s school vacation, they were here [in Vilnius] for three days. In the blink of an eye I met them and had to say goodbye again. Approaching the Vilnius-Minsk bus, a Belarusian bus with Belarusian licence plates – my eyes were filled with tears. I knew I couldn’t go there. I even asked my wife to take and send me the pictures of my house, the trees, the garden…

My mother is 85 years old, and when I was in prison, I was very afraid of not seeing her again. While I was incarcerated, my wife’s father passed away, and although the criminal code has provisions for short-term releases for funerals in such cases, it doesn’t work in practice – they claim there’s no [available transport] etc., so I prayed to see my mother and in August [2023, after the release], I met with my mother, hugged her. I understand that it could have been our last meeting because [now] as soon as my passport goes through the scanners at the Belarusian border, I will be immediately arrested.

100 days after my release [2 November, 2023], a new criminal case was opened against me for “abetting extremist activity,” which carries a sentence of up to six years in [maximum security] prison. Some of my property has been seized already. What the Belarusian authorities have hidden under the word “abetting” is unclear to me, perhaps it’s because I didn’t remain silent… Until a different government comes to power in Belarus that grants amnesty to all political prisoners, I won’t be able to return to the country, and I understand that.

As soon as the slightest opportunity arises, I will return to Belarus… Here in Lithuania, during these six months, I have been trying to engage in the work I did before 2020, which is human rights advocacy as a part of the Viasna Human Rights Center.

How does it feel to be behind bars unjustly? What toll has it taken on you?

I, like other political prisoners, served time without having committed any crime. Serving time without a crime is much harder. Every day there you catch yourself thinking, ‘Why am I here? Why am I in prison? Just because the state labelled me an extremist?’

My family asked me to preserve myself and my health for them, and thoughts of my family helped me survive it all.

[Before 2020] I stood firmly on my feet, I had faith in the law and justice. Between the searches at home and in the office and my arrest, I had 13 days, and I could have left. At that time, Ales Bialiatski told me, “Lyavon [Belarusian for Leanid], you should leave, they might come after you.” To which I replied, “I won’t go, let them leave.” I didn’t feel any wrongdoing on my part, and I didn’t believe in what could happen, which continues to this day. I had that faith until 2020, but it’s no longer there.

After my release, I couldn’t engage in human rights activities in Belarus – if I had started, I would have been arrested immediately. The state deprived me of the right to practise my profession.

If you could talk to your Viasna colleagues who are behind bars what message would you have for them?

To my colleagues from Viasna and all political prisoners, I would wish them to preserve their health. What else? After all, the key to the prison cells isn’t with us; the key is with Lukashenka. Who can influence Belarus today? Putin? – Putin himself has Navalny in prison; he himself has political prisoners.

I would first ask them to prioritise their health as much as possible, because time is passing, and their sentences will come to an end. In those conditions, it’s crucial to preserve one’s health and take care of themselves. I know how challenging it is.

In three years, I lost teeth, and Ales was sentenced to ten years. There’s no dental care; there are people with bare gums who can’t chew their food. I read about a trade union activist who is 73 years old and missing one kidney; he was sentenced to ten years, and he needs a kidney transplant. This is a matter of life and death.

I hope that we all will live to see an amnesty for political prisoners, but I fear that if we have to wait another three years, we might not see many of them again. During my time in the colony, there were three deaths. They would write “minus one” during the morning check, that’s how they treat human life there.

Who will be responsible for the death of Ales Pushkin, a man of my age? I’m sure he would have survived if he was free. What will we do if one morning we find out that Nobel laureate Ales Bialiatski has passed away? Will we say we need to impose new sanctions? I worry about him, he’s my friend.

For six months between our arrests, Ales [Bialiatski] used to write me letters in the Homieĺ prison. He would say to me, “Levon, what can we do for you, Levon, in the autumn [of 2021], you will be home, hold on.”

In your opinion, why were you arrested and sentenced?

For 20 years before 2020, I was engaged in human rights activities in my country, and in [the aftermath of the 2020 presidential elections], I didn’t sit idly by.

There is no legality in Belarus. Now there is a courthouse with people in judges’ robes, but there is no (rule of) law there. As Lukashenka said, ‘Sometimes there’s no time for the law’ – up to today, this lawlessness continues.

In my criminal case, there are 83 volumes with 354 witnesses. These are all people who participated in the protests and were convicted – some received fines, some faced criminal prosecutions. All these people are victims of [political] persecution, and they came to our human rights office for help. I provided not only legal assistance but also consultation, drafted complaints for many, searched for financial assistance to cover lawyers’ fees, court fees, meals [during detention in temporary holding facilities], etc. For this assistance I believe I was convicted. Human rights defenders were later subjected to repression, and I was among the first.

The judge who sentenced me to three years committed a criminal offence, and sooner or later, he will be held accountable for it. He knowingly issued an unjust verdict… When I was in prison, I filed a complaint [against the judge] with the prosecutor general’s office, to which an operative officer returned my complaint and said, “The verdict against you has come into force, which means you’re a criminal, and there’s no verdict against the judge, so he’s clean [innocent]. And if you file another complaint against the judge, we will initiate a new criminal case against you for defamation against the judge.”

I’ve already mentioned that in terms of repression, Belarus is sliding towards the worst practices of its communist past… I believe that the repressed political prisoners will eventually be rehabilitated. I would like it to happen during our lifetime, to witness it.

Why is it important for people to keep sending letters? What do letters of support mean to a political prisoner?

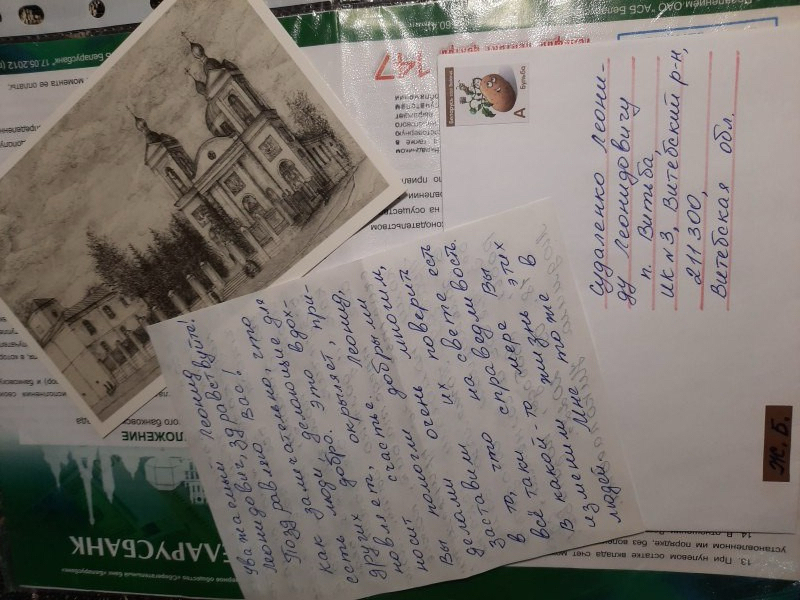

In the pretrial detention centre (SIZO), letters did reach me. There were days when completely unknown people wrote to me, and I would receive 15-20 letters of support. The video where I’m leaving the SIZO with a bag – this bag was full of letters – I brought them from the detention centre to the colony, and then I brought them home. These letters are what I want to keep in my personal archive.

Letters of support came from various countries. It’s heartwarming to receive letters, it is a connection with freedom, with the outside world. It helps you get through, and time passes faster.

For every political prisoner, it’s important to have support, even in colonies where political prisoners are denied the right to correspond. Letters still come, and the censors, the administration, see them, they see this support, they see that people remember and don’t forget the person. Solidarity actions – they must continue. Letters and words of support are very important.

Show your solidarity with a postcard

If you would like to write to a political prisoner in Belarus, Viasna keeps a comprehensive and regularly updated list of political prisoners as well as their mailing addresses. Alternatively, you can send a postcard digitally via volunteer initiative Solidarity Postcards Atelier, organised by activists of the Belarusian Human Rights School and the Belarusian Students’s Association.

After I was released, several people contacted me and forwarded scanned copies of the letters they had sent, but I didn’t receive them (while in the colony). I also received a letter from the prison – as I also helped people there, to write appeals, etc.

What is the future of the human rights movement in Belarus?

Even in the most democratic countries, human rights are violated, so human rights defenders will not sit idle. Even when the political leadership changes in Belarus and there are no more repressions, perhaps then we will defend social and cultural rights. In a sense, Belarus may be fortunate that when democratic rule comes to Belarus, there will likely be an ombudsperson position, and we might even have a Nobel laureate as our ombudsman.

Human rights in Belarus has a future – that’s how I see it. As soon as there’s even the slightest opportunity, many of us will return to Belarus and continue working.

Defending human rights has become the purpose of my life, and I can’t imagine my life without it; it’s all I know. There were times when we worked effectively and managed to defend human rights. I don’t think this lawlessness, this unofficial state of emergency when laws don’t work, will last. Why aren’t the laws working? Formally, they may not work during a state of emergency or martial law, but our country hasn’t declared a state of emergency, so why aren’t the laws working?

Right now, as Lukashenka said, ‘there’s no time for law,’ they’ve created their own world, and they live in that world.

Authoritarian states often seek to defame human rights defenders and portray them as unpatriotic, enemies of society, “foreign agents”. What is your view on this narrative?

In 2020, the authorities committed a crime and continue to commit it.

If we [human rights defenders] are not labelled as extremists, foreign agents who betrayed their homeland, then all the attention will be turned towards the government, because we will demand accountability for the crimes they’ve committed.

That’s why the authorities find it advantageous to create an image of us as enemies and then say, “These are the enemies spreading lies, they’re speaking against the government for Western money, claiming that the government is bad and has committed crimes.” This is the narrative the government continues to uphold.

By portraying everyone who participated in the protests and anyone labelled as an extremist or terrorist by the government as traitors who have sold their country out, they aim to shape public perception. According to this narrative, it’s our fault that people in Belarus are living poorly, and if it weren’t for us, everything would be fine.

Why doesn’t the government grant amnesty, and why do repressions continue? It’s because, in any other scenario, the government can no longer control the situation.

The number of political prisoners today is underestimated because many have already served their sentences, and many don’t want that label. They don’t want to complicate their lives while still in prison.

About 300,000 people have left Belarus, and if they were to return to the country, they would demand accountability from the government. Therefore, the government is doing everything to prevent these people from returning and it doesn’t only apply to human rights defenders, there are journalists, volunteers, trade union activists, scientists, teachers, doctors, and others who are mainly driven by their conscience and have something to say.

Why was I included in the list of top-level extremists? By what right was I included in this list when I don’t even have the opportunity to go to court and prove otherwise? It seems like this label will stick with me for life – when will I be able to get rehabilitation? There is no mechanism for that in the country. By not upholding the law and not providing me with protection, isn’t the government itself becoming extremist?

What is life like as a political prisoner in Belarus?

Every prisoner’s sentence consists of two parts.

The first part, pre-trial detention, is like a prison where you sit 24/7 in a cell and wait for your trial. Some people spend 2-3 months in the pre-trial detention centre. I spent a year [at the Homieĺ pre-trial detention centre]. The second part is when they transfer you to a penal colony [in Leanid’s case] – I spent one and a half years there.

On 18 January 2021, I was arrested, thrown into the pre-trial detention centre, and then forgotten about for about three or four months. Then they brought me into a room with two men in civilian clothes and a video camera on the table on a tripod.

I was offered a deal to cooperate. They said, “What are you doing here, Leanid Leanidovich, among prisoners, among murderers, thieves, and other wrong-doers? You’re an educated person, tonight you could go home, you have a young son”.

In essence, they wanted me to read aloud on camera that the “Viasna” Human Rights Center was planning a revolution in Belarus with funding from the U.S. State Department.

[HRHF asks “so, if you were to cooperate and fabricate falsehoods about colleagues in the organisation, that would have been the price for your freedom?”]

Yes, but how would you live with that freedom afterwards? Even conversations with my wife during short visits over the phone through glass were recorded. And during the trial in Minsk against Bialiatski, Stefanovich, and Labkovich, they read out-of-context phrases from those conversations with my wife. I don’t know what they wanted to prove with that. I only learned about it after my release.

As for the treatment of political prisoners, as soon as you end up there – there’s a violation of any presumption of innocence, even before you’re proven guilty or charged, you’re already labelled an ‘extremist’.

Within about three days, the administration called me in and had me sign some paper. They forbade me to read it and said that they would keep an eye on me. As it turned out, they assigned me to what they call ‘preventive registration’ under the category of ‘inclined to extremism and other destructive activities’. So every time I introduced myself [when being addressed to or receiving food], I had to repeat:

Convict Sudalenka Leanid, born 1966, sentenced to three years under Article 342 of the Criminal Code. Beginning of term: fourteen zero one twenty-two, end of term: twenty-one zero seven twenty-three… I am on preventive registration under the category of inclined to extremism and other destructive activities…

So when someone [from administration] approached the little window of the cell, and called my last name – I had to kneel and deliver this report from the bottom up, and they could have done it an endless number of times, up to 15 times a day. In this way, they drill into your head that you are an extremist. Sometimes you start to think that maybe you really are.

You get one hour of daily outdoor exercise in the courtyard in pre-trial detention, but you’re still under the roof… It was only after nine months that I saw the sky and sun for the first time – when they transferred me to court, and I got out of the police van.

During the year in the pre-trial detention centre, in the dimly lit cell, I lost a significant amount of eyesight, and my teeth deteriorated. I entered with a medical diagnosis of diabetes, and they knew I needed to take daily medication, but during my year in the pre-trial detention centre, they only checked my blood sugar level once, even though I was supposed to have this procedure done daily.

During the three months of my trial from 3rd September to 3rd November (2022), I had 24 court hearings, and they always transported me to court under increased guard. People in the corridor at the courthouse would shy away when they saw someone being led face down like an especially dangerous criminal.

When you’re just a regular prisoner and not an “extremist”, your handcuffs are fastened in front, so you can, after all, use your hands to scratch your nose or ear, but when the handcuffs are fastened behind your back, your nose is itchy, but you can only scratch it against the wall. Once, my nose started bleeding (due to pressure), and I didn’t know what to do – I was in handcuffs behind my back, and I could taste my blood dripping into my mouth.

They do this specifically for political prisoners. It’s not just one day – in the morning, they bring you (to the court), then they take you back for lunch to the detention centre and back to the court after lunch, and then again in the same manner in the evening at six pm, bringing you back and forth. In total, four times a day, 24 hearings like this, and you can go through about 100 transfers like this in my case. It’s quite humiliating.

[During] the hearings, you sit in a cage, a cell. This also violates the presumption of innocence. I [unsuccessfully] filed motions to recuse a judge every day because it created uneven conditions – the prosecutors, three of them, sit at the table, and I am in a cage… I couldn’t even make any notes during the process.

In the colony [where I was transferred after the court’s decision], I was held with the status of a “persistent violator” until the very last day [of the sentence]. I was afraid to tell my family what it might mean. According to Article 411 on “persistent non-compliance with the terms of serving a sentence,” a person in a judge’s robe can add new term [during the initial term] – [Zmitser] Dashkevich had it added, Palina Sharenda-Panasiuk had it added for the second time within a year. I was afraid of this, and I understand that the status of a “persistent violator” was not given to me for nothing, they were preparing to add a new term for me.

The status also meant no right to visits.

As soon as I applied for [the possibility to have visitors], they immediately found a reason to deny me a visit – a button was not properly fastened, or my shaving was not done correctly.

28 out of 100 prisoners in my section were political prisoners, and they can be easily distinguished – as soon as you arrive in the colony, they put a distinctive mark on political prisoners – a yellow label, which means “extremist.” Out of the 28 “yellow-label” prisoners, only one other guy and I had the status of “persistent violators”.

Every day was the same there, except for Sundays when we didn’t work. All inmates had to work. For the first nine months, I worked in the woodworking shop, then I was transferred to the metal dismantling shop – extracting metals from old cables with bare hands. There was a quota for how much copper had to be handed over, otherwise, it would lead to the SHIZO [punitive isolation]. For this work, six days a week for eight hours, I received less than one USD per month. I assume the rest was deducted for utilities. There were no vacations due to my status, unlike [the situation with] other inmates.

I was also not allowed to correspond, and when I approached the administration, they told me that receiving letters from my wife was enough, and if I raised this issue again, they would send me to the SHIZO.

I also went to the SHIZO [punitive isolation] ten days before my release, they transferred me there for no reason, saying, ‘You have ten days left, you’ll have the opportunity to clear your thoughts, be alone.’ It is a prison within a prison, torture with cold, torture with solitude.

Three times a day, they give you porridge and a sweet tea, which I couldn’t drink due to diabetes – on the seventh day, I was already talking to a spider I found in the corner, singing songs to avoid losing my sanity. A person needs communication.

There is no bedding there, they take away warm clothes. You can’t sleep for over an hour because of the cold. I was there in the summer, but at night, the temperature was around ten-12 degrees Celsius, and there was an open barred window that you couldn’t close.

You can’t get proper sleep, and they don’t allow daytime sleep either – I laid down on the floor during the day, and I received a reprimand. I consider it torture, and I spoke about it, even refused to eat Their response was that “it’s the law”. When I got out [of prison] and checked, indeed, there’s such a law that inmates in the SHIZO are not provided with bedding. They even included this torture norm in the criminal code.

I understood that if I didn’t get out [of detention], I wouldn’t have survived that SHIZO, I couldn’t take it anymore.

Honestly, I didn’t think they would release me until the very end. I thought that on the last day, they would take me to court, invent a new term, and simply wouldn’t release me. Even when they released me, I took my first steps to freedom, and I didn’t believe it.

They released me and told me to go to the bus stop [public transport] to travel eight kilometres to the city. But I knew my family would come for me. They woke me up at five am, gave me porridge, and at six am I was released. I was waiting for my family until 11 am because usually, they release everyone at that time [and this is the time the family was asked to come].

They didn’t allow me to change into my own clothes, after I lay on the floor without a shower for ten days.

How can people around the world continue to support Belarusian civil society?

This is a complex and simple question at the same time. President Duda [of Poland] has spoken out, saying there are no effective means left to free Belarusian political prisoners.

We need to make political prisoners a serious problem for Lukashenka and present him with an ultimatum he can’t refuse. Sanctions aren’t enough while potassium fertilisers [are being exported from Belarus]. It’s worth trying to exert more decisive pressure on Minsk.

I’m grateful that the Belarusian agenda is not disappearing, and, in relation to the Belarusian regime, all European countries have a consolidated position, except perhaps Orban.

We shouldn’t forget that rockets were also launched from Belarus towards Ukraine. I learned about this when I was released from prison. But it’s not the fault of Belarusians; there was no referendum asking, “Are you willing to allow Belarusian territory to be used for the Russian army against Ukraine or not?” It was Lukashenka’s decision, and he should bear responsibility for it.

Is it the fault of Belarusians that rockets were flying from my hometown of Homieĺ towards Chernihiv, where I grew up, and which we (family) visited weekly? When I found out that Chernihiv was bombed, it felt like they were destroying my own home. How can you forgive that?

I hope that this madness, or rather, what’s happening now, can come to an end, perhaps in the new year, the Year of the Dragon starting in February. I got into horoscopes during my time in prison [laughs]. I hope that 2024 brings us good news because the outgoing year has been a catastrophe. There’s a war in Ukraine, people are dying, and in Belarus, it’s a quiet war, and people are dying there too. Not in the same numbers, but today we’re talking about Belarus.

About Leanid Sudalenka

Leanid Sudalenka is a human rights activist, and head of the HomieÍ branch of the Human Rights Centre Viasna, with 20 years of experience helping citizens affected by human rights violations. Sudalenka has assisted in the preparation and submission of numerous individual complaints to the UN Human Rights Committee against Belarus.

Throughout 2020, Sudalenka provided legal assistance in challenging the rulings issued by the court for participation in “unauthorised rallies” taking place in HomieÍ after the 2020 presidential elections.

Top photo: Yauheniya Parashchanka.