Following the illegitimate 9 August 2020 presidential election, protests erupted across Belarus, prompting an unprecedented crackdown from the authorities which continues unabated. One year since the election, hundreds of political prisoners remain in the country.

Letters from Lukashenka’s Prisoners, gives unjustly detained individuals a voice by collecting, translating, and publishing letters on our channels. This campaign is a collaborative project by Belarus Free Theatre, Index on Censorship, Human Rights House Foundation and Politzek.me.

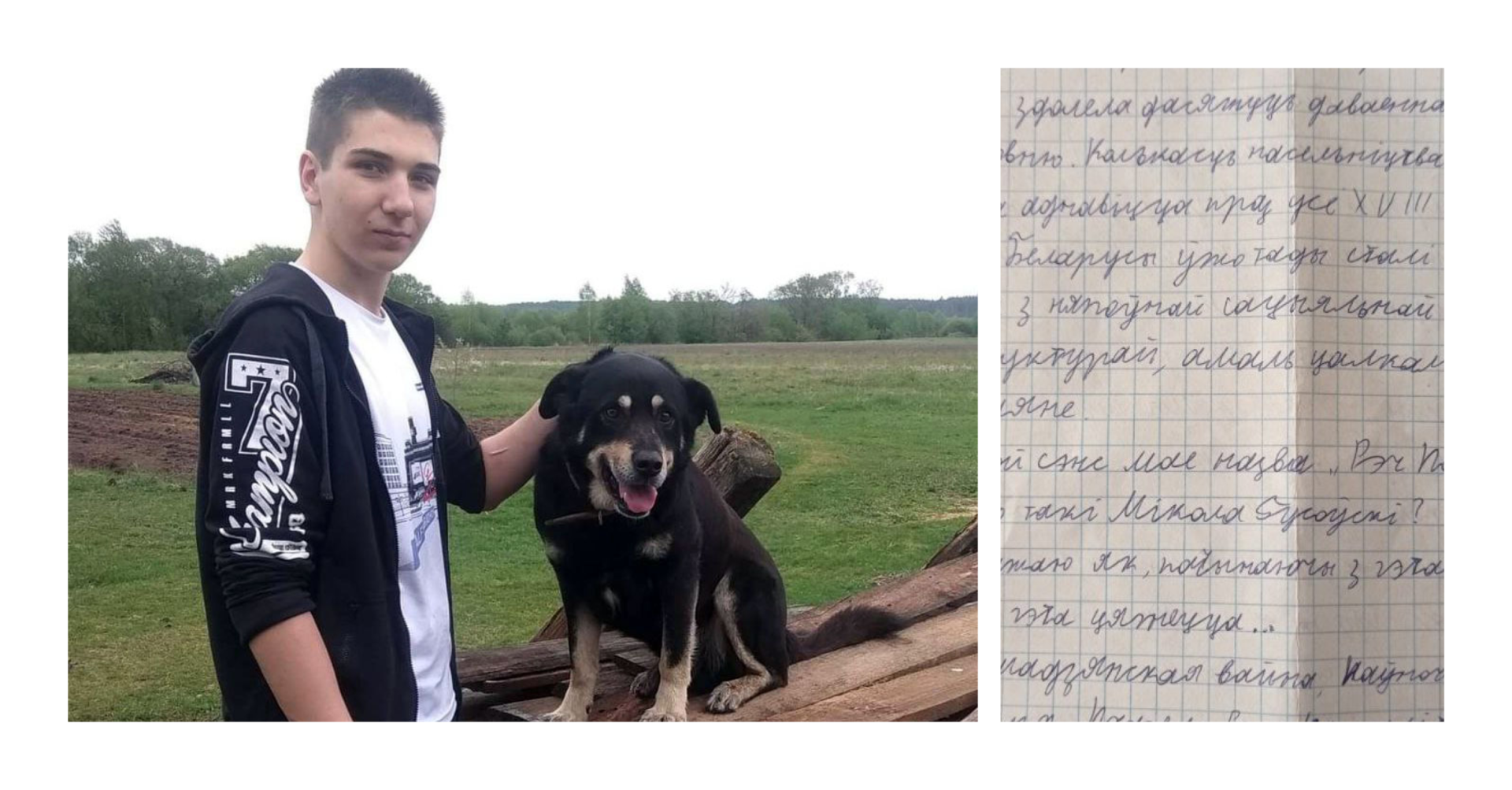

Read more about Artsiom Mitsuk and other Belarusian political prisoners here.

Translations are available in Russian and Belarusian here.

On the morning of 30 September, Artsiom’s mother received a call informing her that her son had been detained as part of a criminal case. Later the same day, the authorities arrived to search their apartment. Nothing was seized in the course of the search. On 9 October, Artsiom was charged under Part 2 of Art. 293 of the Criminal Code (participation in riots).

Eleven people in total, including Artsiom, were arrested related to their involvement in different Telegram chats, some of which were defined by the Belarusian state as “radical”. When he was arrested, Artsiom had several printouts of “Честная Газета” (“Honest Newspaper” – independent self-published newspaper) with him – he believed that people needed to be able to share information about what was really happening in Belarus. The prosecutor noted that this “points not only to the opposition, but also to the subversive activities” of Artsiom.

On 19 July 2021, Judge Dzmitry Astapenka sentenced Artsiom to eight years in a medium-security penal colony. During his imprisonment Artsiom quit smoking, began to correspond in Belarusian (his mother tongue is Russian), read a stack of books – among them Hemingway, Karatkevich, the Strugatsky brothers, Aleksievich, Remarque and many others. He has also become interested in the history of Belarus and philosophy. These new interests are evident in his letter to his dad, Siarhei that starts with a list of books that Artsiom is planning to request from his relatives. The letter reveals a young mind exploring as widely as he can, from within the confines of a prison cell, including significant moments in Belarusian history. This included fictional and historical representations of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the January Uprising of 1863 – 1864, which saw Poland, Belarus and Lithuania (which included parts of modern day Ukraine and Latvia) attempt to oppose the Russian Empire. Access to books, including history books, appears to be a lifeline for Artsiom as he plots the legacies of different wars and empires, and how they shaped and continue to shape Belarus. This curiosity culminates in the powerful allegory between Albert Camus’s The Plague (itself an allegory for the rise of fascism) and his current imprisonment, from the institutional setting, the rigidity of routine, and also the transformation of every moment resisting despair into a series of heroic deeds. –

Letter:

Hi!

Starting with the books:

- Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand

- Return of the Primitive, Ayn Rand

- Spartacus

- Former Son, Sasha Filipenka

I will apply for this list.

On the regular parcel: health is the priority. So, some chocolate, dried fruits, nuts, simple salo, porridges, some cheese. Fridges are here, but sometimes they are full. So when you have time and opportunity!

Actually, I’m used to how it is. And who knows, I might break some rule at the last moment, and they will not give me my parcel 🙂

My moods were somewhat down over the last couple of weeks. Couldn’t collect myself.

Reading Ears of Rye under Thy Sickle [a novel by Uladzimir Karatkevich published in 1965 about the events on the eve of the uprising of 1863-1864, which sought to restore the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth], I remember my own words that you had noted. Well, not exactly my own 🙂 Like Raŭbič and Zahorski, who became enemies in the Ears of Rye, while sharing, basically, the same goal.

They banned my parcel while I was writing the letter. Well, ok.

I think I have found a good history book from what I’ve seen here, authored by Bochan, Holubieŭ and Jemieljančyk. Six volumes. I only have the third one, The times of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, 17th-18th centuries. It describes the war of 1654-1667 and the people’s struggle when it became clear how occupiers hunted people, including well-skilled craftsmen, and took them away. And how crafts never fully recovered because of that. The population never recovered across the 18th century. Back then, Belarusians were left with high levels of social instability, since almost only peasants survived.

I keep thinking how things remain defined by that war. The Civil War, the Great Northern War, the partitions of the Commonwealth, the Russian Empire, the uprisings, the First World War, Stalin’s hell, the Second World War, and USSR in the end.

I’ve learnt that Suvorov was granted the rank of field marshal for the ‘pacification’ [Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov was a Commander from the Russian Empire during the pacification of the Bar Confederation of Poland, which was established by Polish nobles on 29 February 1768 in the town of Bar in Podilia (in modern day Ukraine) to defend Poland against the Russian Empire].

Wars, uprisings, Muravyovs [Mikhail Nikolayevich Muravyov was known as the ‘hangman of Wilno’ for his brutal suppression the January Uprising, while his grandson, Mikhail Nikolayevich, Count Muravyov was a Russian diplomat, who directed Russia’s activities in east Asia in the lead up to the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05)] and other butchers, more wars, more uprisings, and butchers again. This all lasting over 350 years. It is challenging to keep courage and honour. It is challenging not to become a coward, indifferent to public life. The cycle repeats itself.

I’ve read The Plague by Camus. It describes a disease coming to a town, a metaphor of opposing fascism.

The main thing I have noted was the routine. The main character goes to the hospital every day and handles the disease. Many do the same. Same essential work every day, life risks every day, and heroism every day.

Rather than one heroic deed, it’s all the same hard work every day. When one day you find a way to do more, you do.

Not everyone can find a way to do better, so they do what they can every day. It’s about doing your thing every single day. Fighting the disease is of course heroic, but this is also the most reasonable and sensible thing to do. In fact, it is not clear how it could be otherwise.

Fighting every day to get closer at least by one minute to the day when the sickness is gone.