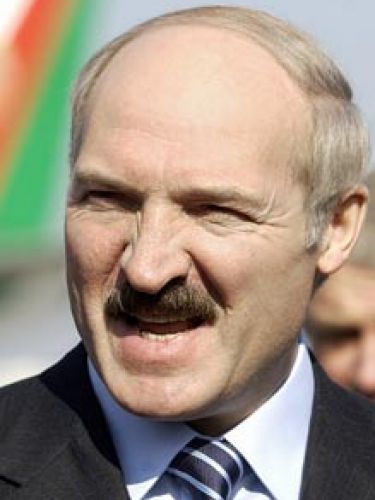

Belarus has changed a lot in 15 years in spite of the dictatorship. Its economy has grown at twice the rate it has in neighbouring Ukraine. This is a Chinese, or rather a Singaporean model. Lukashenko is convinced that it is the one best suited to the Belarusian mentality and geopolitical situation. Not everyone agrees with him. A parallel society has grown up. Rock music, samizdat and discussion clubs are all flourishing.

In order to catch this wave, Lukashenko is ready to commandeer what used to be the opposition’s seditious slogan “For Freedom.” “The principle that everything not expressly banned will be legal in this country…” he writes in the short version of his election manifesto.

“Getting richer”

Prior to his fourth term in office, Lukashenko is promising prosperity, and a move towards European standards. Good Bye USSR! Gone are the dreams of “reviving the Great Country.”

Lukashenko’s manifesto assigns some populist, yet realistic goals. “Belarus must become one of the top 50 countries with the highest human development index,” Lukashenko writes.

Lukashenko assures us that “private property will be developed.” This is the same Lukashenko who called private businessmen “lousy fleas” ten years ago, and described the country’s system as “market socialism.” He is now proudly announcing that “Belarus has become one of the top four reformers in the world, in order to facilitate the running of businesses.”

NEP, Lukashenko-style

Lukashenko 1.0 believed he could conquer the Russian throne. Lukashenko 2.0 attempted to thwart a coloured revolution at any cost. Lukashenko 3.0 wants to wind up among the world’s Top 30 business-friendly countries.

Lukashenko, a born populist, cannot fail to follow public opinion. In 1995, 70% of the population were in favour of reviving the USSR, but the figure is hardly 10% now: three times less than in Ukraine.“Daddy” Lukashenko is no longer a father of nations, or a Stalin. He is the father of a nation apart. Lukashenko demands just one thing in exchange for economic freedom: don’t touch my authority.

The opposition’s violations

“The parliament and president were never elected undemocratically in our country,” Lukashenko stated bluntly to the Polish and German foreign ministers. “I’ve already said it openly: close your eyes to all the violations committed by the opposition,” Lukashenko added. It’s true, these elections will be no worse than previous ones. The amount of opposition members included in electoral commissions is 0.25%. There are no changes in the media either. Opposition candidates are being allowed on television as talking heads, but only as many times as stipulated by the liberalised electoral code, and no more. “The opposition is necessary because the West wants it,” says Lukashenko for the internal audience. The state officials conclude: “Don’t you dare rock the boat!” Average Belarusians recall how the Soviet NEP [New Economic Policy] was replaced by a wave of repression.

How to break through the concrete

The long-term leader of the Belarusian opposition, Aleksandr Milinkevich, refused to run as a candidate, saying “I do not wish to take part in a show controlled entirely by one director.”

This boycott was seen as unproductive, however, and so the liberal-conservative camp has put forward its own candidates, albethey lesser-known ones. Neither the conservative Ryhor Kastusiou, the Christian democrat Vital Rymasheuski, nor the liberal Jaraslau Ramanchuk have even been leaders of their own parties.

Tell the Truth

And there is a third force at work – the Tell The Truth campaign. “Tell the truth, where’s the money coming from?” the opposition jokes.

Lukashenko has also stated that “the opposition candidates Uladzimir Niaklajeu and Andrej Sannikau are people who are being financed by the Russian Federation today.”

At the helm of the Tell The Truth campaign is a man who would seemingly have very low chances of success with the Kremlin: Uladzimir Niaklajeu, a former TV presenter, Belarusian-language poet, and author of an erotic novel. Niaklajeu and Sannikau are in favour of improving relations with the Russian Federation. Lukashenko’s manifesto does not even mention the Russian Federation or integration with it.

the Russian Federation and the West have changed places

“Russia and the West have changed places for these elections,” says Vital Silitski, director of the Belarusian Institute For Strategic Studies.

The strongest signal came from Lithuanian president Dalia Grybauskaite. She is supposed to have said “Lukashenko is a guarantor of economic and political stability, as well as independence” at a closed meeting with EU ambassadors. Belarusian opposition websites got emotional following Grybauskaite’s statement: “Europe’s political prostitution!” fumed the commentators. Civil society leaders fear being betrayed by the West. They are afraid of being left alone with authoritarianism, forgotten and disregarded. Previously, Moscow called Lukashenko a son of a bitch, but our son of a bitch. Now, Polish and Lithuanian diplomats in Minsk are vying with each other to question local experts: is Lukashenko ready to function within a guided democracy? Is he prepared to maintain power while toeing the line? “Recognition or non-recognition of the elections should be defined not by the [geopolitical] calculations, but only by the elections themselves,” says Silitski, a political scientist.

He’s afraid of the Russian Federation

Ten years ago, Belarus was the most pro-Russian and one of the least democratic countries of the former USSR. That is no longer the case today.

Therefore, it is an erroneous cliché to think that no Western policies (either isolationist or engagement) have been successful in Belarus. On the contrary, the West has shown the right amount of tenacity and flexibility at the right time. In the past, many saw [Lukashenko] as an irrational dictator; a Caligula with a hockey-stick. Lukashenko has proved that he is capable of change. If oil and gas will pass Belarus by as they flow through the Nord Stream and BTS-2 pipelines (which will already happen in 2012), economic evolution will lead Lukashenko even further into the West.

So far, political progress is impossible. The best ways to bolster Belarusian independence are economic cooperation, support for Belarusian culture and civil society, and opening up the borders for Belarusian citizens.

The first dictator in Europe

In his manifesto, Lukashenko mentions liberalisation for business initiatives: “Everything not expressly banned will be legal.” But the manifesto says nothing about national identity or the Belarusian language, not to mention democracy. He wants the West to accept him just the way he is. Condoleezza Rice once called him “the last dictator in Europe.” Now he wishes to become the first dictator in Europe to have gained tacit acceptance. He is willing to be the West’s client, as long as they do not demand too much from him.

* * *

Andrej Dynko is editor-in-chief of the newspaper Nasha Niva / NN.BY, which became legal once again thanks to EU pressure in 2008. For several years he was the head of Belarusian PEN, which is one of the member organization of the Belarusian Human Rights House. Winner of an international Oxfam Novib / PEN Freedom of Expression Award and a Lorenzo Natali Prize, as well the Russian Channel 1 prize for journalistic courage and professionalism. Vaclav Havel awarded him part of his own Ellenbogen Citizenship Award, calling Nasha Niva “a symbol of independence [and] an island of freedom.” Nasha Niva got the Norwegian Fritt ord award in 2007.