Almost 12 years after the start of the occupation of Crimea and nearly four years into Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, enforced disappearances and incommunicado detention have become a defining tool of Russian repression on the occupied peninsula and in newly occupied territories of Ukraine.

Human Rights House Foundation spoke with a Crimean human rights defender (referred to from this point forward as CHRD) representing Crimean Process, member organisation of Human Rights House Crimea, about how their work has evolved since the first years of Russia’s occupation of Crimea, what enforced disappearance means in practice, and why they believe that international actors must “demand more” for civilian hostages. The identity of the CHRD has been withheld for security reasons.

Crimean Process, an initiative uniting legal experts and human rights activists, emerged in 2016-17 as an urgent response to a wave of politically motivated prosecutions in Crimea. Recognising that verdicts issued by the occupation courts would be unjust and fabricated, the group developed a systematic, evidence-based methodology for monitoring trials. Over time, their work expanded from observation to analytical reports and contributions to international accountability efforts, including submissions to the International Criminal Court.

Waves of enforced disappearances in Crimea

Since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Crimea has become one of the territories where civilian hostages from newly occupied regions were taken and held.

“There were many questions: who was being held, where they were being held, and what the conditions were. Our initiative works directly on the ground, and sometimes we were able to obtain the necessary information… This avalanche of cases forced us to shift our focus specifically to civilian hostages and civilian detainees.”

Starting from the end of 2023, Crimean Process began to observe a large-scale shift in the use of enforced disappearances as political persecution in Crimea that would resemble the treatment of civilian hostages from newly occupied territories, marking a new, escalated phase of enforced disappearances. Read more about the waves of enforced disappearances in Crimea

“Now a person disappears, and nothing is known about their situation for a long time — but after a while, we receive signals about where they are. Then, not all, but most of these people reappear as defendants in criminal cases, with a gap of a year or more.”

CHRD cites the case of student Anna Yeltsova, abducted in December 2022:

Around March 2024, [a Russian court] announced that they had ‘detained’ a student from the Kherson region who was about to be convicted. But where she had been for those two years — no one ever explained.

Behind the terms: enforced disappearance and incommunicado detention

According to CHRD, in practice, an enforced disappearance means a person is taken away in an unknown direction by or with the involvement of state agents, denied access to a lawyer and contact with family, and their detention is not officially acknowledged.

In practical terms, when held incommunicado, the person is detained in a facility where, for example, the windows may be painted over so they don’t know what time of day it is. They have no means of communication. Lawyers are not allowed in. Any inquiries from relatives are met with: ‘Such a person is not here’.

“The authorities refuse to acknowledge that they are holding the person. Officially, the detainee does not exist in any legal status; there is no formal responsibility for their life or health, and if anything happens to that person, ‘no one will find out’.”

“This stage can go on for quite a long time. [Victims] are told that some ‘verification’ is being carried out and that if they want it to end sooner, they have to ‘do something’ — for example, admit their guilt. They can remain in that status for years, with no access to any channels of communication with the outside world — not even to news.”

In CHRD’s experience, the cases of enforced disappearances almost always come with torture.

Torture is, sadly, part of the process. Usually, if a person has been abducted, they are later tortured and only after that, during the investigation, they are forced to ‘confess’ to something.

“[Occupying authorities] have a wide ‘assortment’ of torture methods, but they most commonly resort to beatings and electric shocks.”

“Right now, there are also many women among the victims of enforced disappearances — and we notice a specific additional form of abuse during their incommunicado detention:

“Women may not be allowed to wash for a very long time, and are not given any hygiene products…which together with other conditions of such detentions creates unrelenting psychological pressure.”

He recalls one case in which an attorney summarised his client’s situation:

She agreed to ‘plead guilty’ on the condition that she would be given two small packets of shampoo… People are driven to such a state that they are ready to admit to anything just to regain some minimal dignity.

Residents of newly occupied territories who passed through local “courts” and local investigative bodies describe an additional stage:

“There are ‘pre-investigative beatings’ — that’s what victims themselves called it. They would be taken out of the cell, brutally beaten and told that this was ‘just the beginning’ — a warning that if, during interrogations, they denied anything or refused to cooperate, there would be even more severe beatings afterwards.”

“Sometimes the beatings were so severe that an ambulance had to be called to stitch up their heads.”

Measuring repression by examining the capacity of Pre-Trial Detention Centre No. 2

One of the key challenges of enforced disappearances, according to CHRD, is that such cases are extremely hard to document, and many may remain completely unknown.

Some cases only come to light completely by chance, and very late. For example, a person disappeared two years ago, and we only find out about it now — after their trial has already taken place. So they spent a year in isolation, then another year under investigation and in court, and only after the sentence do we learn that this story happened at all.

There are many Crimeans who reach out searching for loved ones abducted by Russia’s FSB.

Relatives [living in the occupied territories] often do not understand what they can do and fear making things worse by going public. There is also a widespread feeling that speaking out brings only risk and no tangible support.

“In addition, relatives fear that they themselves may be abducted or persecuted as well… They also don’t see any benefit of going public that would outweigh the risks.”

We face a situation where some cases never become known at all, and others that we know about remain non-public for a very long time.

In addition, it is impossible to monitor the real situation on the newly occupied territories as the occupation “courts” set up on those territories do not publish information on the cases, while “an observer can not safely enter the region without risking ending up disappearing themselves.”

“The criminal prosecutions are somewhat easier to track now as Russia is keen to show publicly how it deals with so-called ‘spies and saboteurs’.”

CHRD says that the capacity of the pre-trial detention facility, where incommunicado detainees are held, reveals something of the scale of repression. This facility in Crimea, known as Russia’s FSB-controlled Pre-Trial Detention Centre No. 2, has the capacity to hold around 450 people.

“Of these, approximately 300, in our estimate, are people under formal investigation, and up to 150 are reserved specifically for people held in incommunicado conditions.”

At one point, Crimean Process’ analysis suggested that up to 120 people from the newly occupied territories were being held there incommunicado. Many of them have since been sent to Russian colonies and prisons, but the cells have not remained empty:

“New detainees are brought in, increasingly from Crimea itself.”

“These women were abducted and have been held in isolation for over a year”

CHRD cites several cases of women who have been in isolation for over a year following their enforced disappearances, which they say are emblematic of the situation. Among them is Tetyana Diakunovska from Sevastopol, abducted in August 2024 – the fact that Diakunovska was being held in Pre-Trial Detention Centre-2 in Simferopol in complete isolation was reported by another victim of enforced disappearance. Three women – Elvira Aboiazova, Larysa Haidai and Tetiana Pavlenko (Symonenko) – who have been ‘found’ in the same location in August 2025,18 months after they were abducted and vanished, with no currently known charges against them and all of them being held incommunicado.

A somewhat unique case mentioned was a case of Sakha Mangubi.

“This is the first case on our sad list of persecution of Crimean Karaim by the new Russian repressive machine. Moreover, there are signs that a domestic conflict was behind it — apparently, someone took advantage of an argument and made a false accusation, which became the reason for her persecution, enforced disappearance, and subsequent detention in isolation.”

“Let’s talk about Crimea later”

In 2025, Crimean Process, HRH Crimea and Educational Human Rights House Chernihiv, are implementing a House-to-House project with the financial support of Norway to support families of the victims and strengthen the response to enforced disappearances in occupied Crimea and southern Ukraine.

Overall, there is a growing tendency to say: ‘We’ll talk about Crimea later,’ but people are suffering now. They are being repressed now.

CHRD says that the issue of enforced disappearances is certainly little known among Crimeans themselves, because many of these cases are hidden. “Even those who seek out alternative information via VPN and independent sources don’t see the full picture.” At the national level, this topic doesn’t stand out among other war-related issues, whereas at the international level, it deserves much greater attention:

“With regard to the abduction of children, we can say with confidence that diplomats and experts know and agree: Russia abducted children. It must return the children, pay reparations, and be held accountable… The issue of returning children is clearly acknowledged as urgent. The issue of returning their parents and other adults is not treated as equally urgent. This is wrong.”

“The same approach should be applied to civilians. This is a very complex process that requires major effort on the part of diplomats in partner countries.”

What happens if Crimea is not de-occupied

There are calls to ‘be realistic,’ to acknowledge ‘the realities on the ground,’ and so on. But the question of territory is not more important than the question of people. We need answers to what will happen to the people.

“If conditions can be created under which Crimea becomes a special territory with access for international monitors and with a direct link between the human rights situation there and sanctions — which was and still is extremely difficult to achieve — then I’m sure Crimea could be in a relatively acceptable state, nothing like what we see now — the North Korea–style reality that Crimea resembles today.”

“Therefore, if the hot phase of the [full-scale war] ends without the liberation of Crimea, and there are no clearly defined mechanisms for monitoring human rights, for returning people who have already suffered, for guaranteeing that such repression will not be repeated — then of course Russia will ignore everything and will continue to do whatever it finds convenient, including gross violations of human rights, just as it has done all these years.”

CHRD echoes the words of political prisoner Iryna Danylovych:

When Danylovych was awarded the ‘Stories of Injustice Award 2025’ prize in Prague, she managed to send a short speech to be read in her absence. In it, she said that difficult times demand decisive action rather than mere statements of ‘concern’.

Only decisive action can change what is happening and bring about positive change. For that, we have to demand more.

Letters for political prisoners: beyond one-way solidarity

In 2020, already years into Crimean Process’ trial monitoring, one pattern became clear for the team, says CHRD:

“Crimean political prisoners usually ended up in Russian detention facilities after standing trial in Crimea. There are very harsh conditions of detention there and inhuman treatment of detainees. This is why we initiated campaigns to write letters to Crimean political prisoners — it was aimed both at moral support and at analysing the situation in the places where political prisoners are held.”

According to CHRD, systematic letter writing is difficult to maintain: people struggle to find time, they don’t know what to write, it’s logistically complicated to send letters, especially from Ukrainian-controlled territory to Russian prisons, and finally, if a reply comes, sustaining a long-term correspondence is even harder.

Right now we have some logistical problems with getting these letters into places of detention, but the main difficulty remains getting people to keep writing letters and participate in the correspondence.

The team experimented with different formats, including recruiting dedicated volunteers for regular correspondence and using technology to simplify letter-writing.

“With Human Rights House Crimea, we developed a simplified format for writing letters: a person answers a short questionnaire — what movies they liked, travel plans, books, and based on that, a letter draft is generated by AI — readable, interesting, and still carrying the person’s touch and personality.”

Readers can write a letter to Crimean political prisoners using this form created by Crimean Process and Human Rights House Crimea as part of the wider campaign by Ukrainian civil society.

Still, CHRD stresses that the goal is not just one-off messages of support:

A person in captivity is in very difficult conditions. One-off letters do confirm that they are not forgotten — but they don’t give them the feeling that someone is genuinely interested in how they are. That someone cares about their health, their thoughts, their feelings.

Giving political prisoners a voice and sustained contact is vital for their dignity and mental health:

“We want to give them a voice — so they can talk about their thoughts, dreams, interests. To engage them in an activity where they’re not just reading but also thinking and responding, to give them something that pulls them away, at least a little, from the reality they are in.”

This is how Leniie Umerova, a Crimean Tatar activist and former political prisoner, explains the importance of letters for the victims of unlawful detentions and their relatives.

For a person in captivity, every letter is proof that they haven’t disappeared between the prison walls. It is vital support — a fight for the person, giving them faith in liberation. For families, it is also a source of strength — knowing that their loved ones are seen and heard, that their suffering has not become “just another statistic.” This support relieves the feeling of abandonment and gives them the strength to keep fighting.

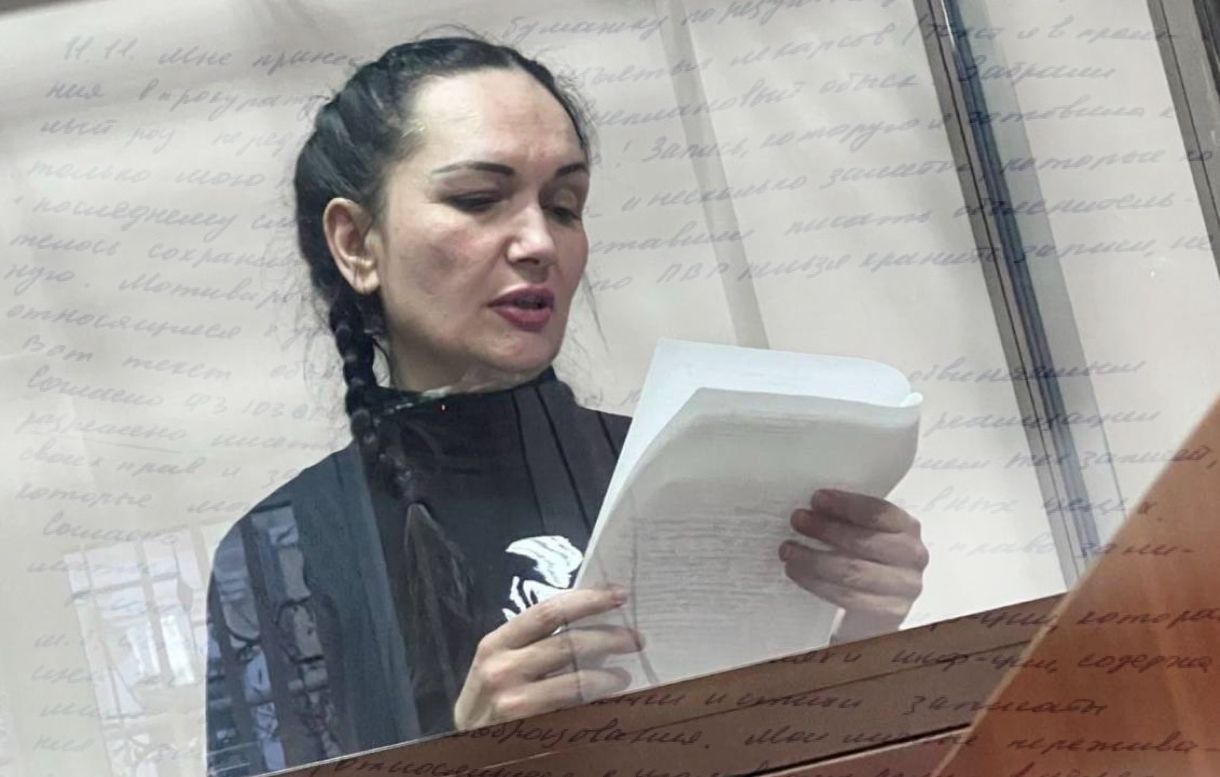

Top photo by Taras Ibragimov, exhibited as part of “Stories from occupied Crimea”.