The visit of the Lesia Ukrainka Theatre was organised by HRHF and Norway’s National Theatre, and was made possible thanks to the support of Fritt Ord, the European Union, Mental Health and Human Rights Info (member organisation of Human Rights House Oslo) the Norwegian Ministry for Foreign Affairs, and is a part of the Nobel Peace Centre’s “Nobel Peace Talks”.

HRHF first met representatives of the Theatre as part of a visit to Ukraine in October 2022 to meet and show solidarity with local partners from the Network of Human Rights Houses, as well as other members of Ukrainian civil society.

Hi Viktoria, welcome to Oslo. Can you please tell us about Lesia Ukrainka Theater?

The Lesia Ukrainka Theatre is a municipal theatre in the western Ukrainian city of Lviv. Our mission is modernising Ukrainian theatre and working to show and familiarise the world more with Ukrainian culture.

To do that, we educate, share knowledge and work to create new experiences. We support contemporary Ukrainian dramaturgy – young artists, actors and directors.

There is a common position that the theatre is something only for entertainment and nothing more. This position does not interest our team.

We try to produce something beyond theatre, something multidisciplinary, something that involves minds from different fields – we are interested in exploring how theatre can combine with ecology… literature, for example.

Our team started working together in 2017, and I think that… actually, I don’t think it – I am absolutely certain over the last six years, we’ve done some great things together and I’m proud of how the Theatre has developed during this time.

What is “Imperium delendum est”?

“Imperium delendum est” [The Empire Must Fall] is the first art piece produced by the Theatre following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine.

From February to around May 2022, the Theatre was used as a shelter for refugees and our team worked on helping people who were evacuated to Lviv. Helping people was the most important thing that we could do – it’s also all we wanted to do.

But in April, the City Council knocked on our door and said “come on, you are a theatre, you are supposed to make art.”

Our team was so angry because there was so much work to be done and instead, we were told to make art.

There is an obvious irony because art is our main direction, but this is a war situation and to us only helping people was important. And so, we were the last theatre in the city to start working again.

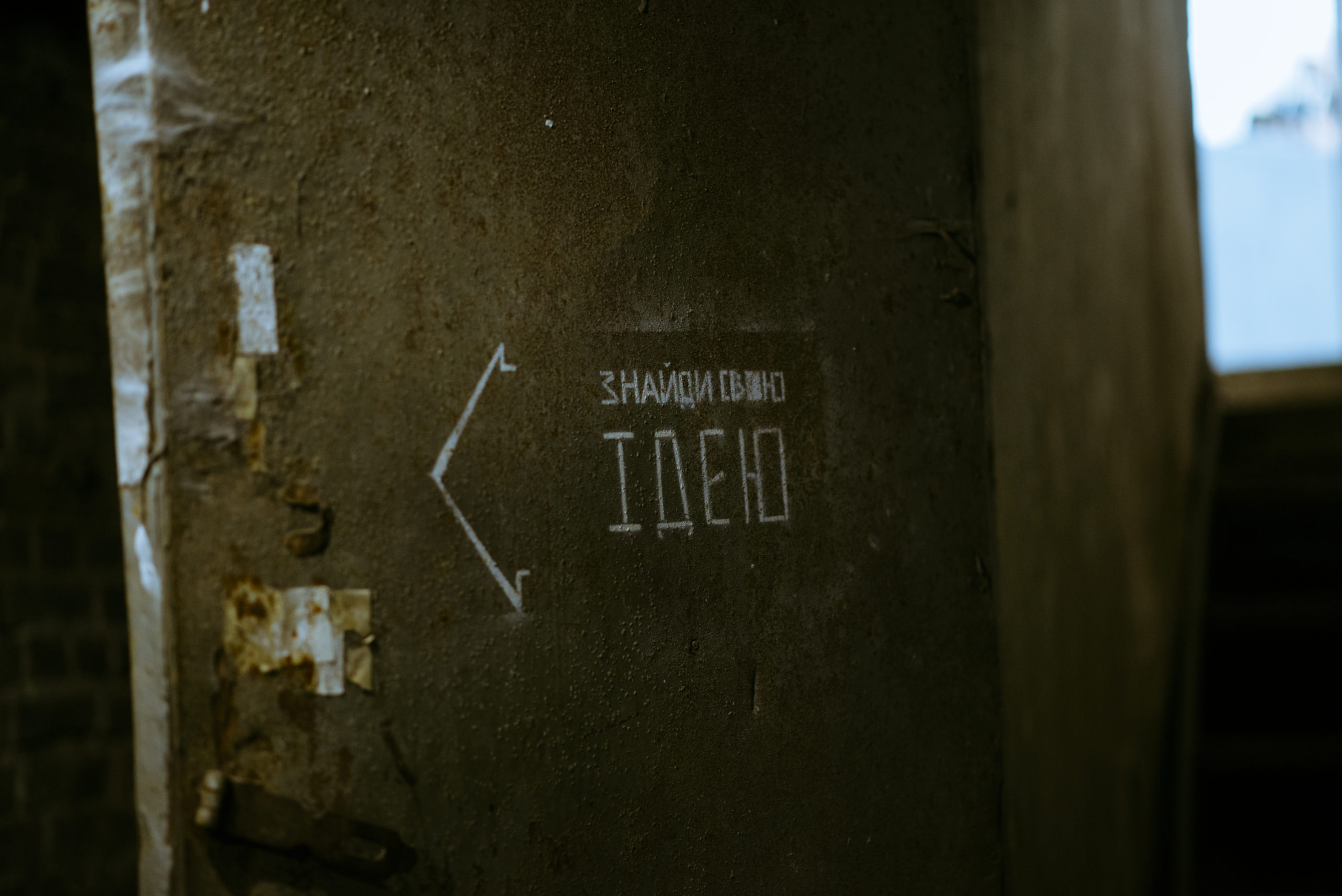

We started with a couple of actresses and our director Dmytro Zakhozhenko. They met and just discussed what they wanted to do… what they could do. Did anyone even have any ideas? They asked me, they asked the board of the theatre, but we had no ideas… nothing. But step by step, the actresses and Dima [Zakhozhenko] they kept talking.

There was anger. They were angry, and they were searching for something… alive in that moment… something that had some meaning amongst all of this meaninglessness.

And so, then came poetry. Poetry was everywhere at that time. A lot of our friends are poets and poetry was all over social media. Poetry helped to voice our feelings about this moment in Ukraine.

Poetry was our first step and our next step was song. That was a bit unexpected as we didn’t work much with poetry before.

Almost all of our actors and actresses sing – a lot. We began to discuss that this could be the form that our reaction takes, encompassing our natural and genuine feelings and emotions.

The first open rehearsal of “Imperium delendum est” was extremely moving. Everyone in our team just cried.

Later, we saw that there was an enormous reaction from our audience to this performance. We didn’t expect so much feedback – feedback both in-person and on social media.

In the end, we discovered that somehow we found this form that would also allow other people to feel a sort of relief through theatre.

I thought initially that our incredible piece of art would be so touching and strong maybe only for about six months. After that, we might have lost these emotions, the fury, the anger. Because this performance is pure fury and pain – our very first reaction. But now, almost two years later, I see how wrong I was.

Why are there only women performing in the production?

In our Theatre, we have more women than men in general, but after the start of the full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s borders closed for men. What that means practically for us is that if we want to bring our performance abroad, there are new situational considerations to think about.

However, we didn’t actually think about any of that when we started the work. Our men were busy with other activities – helping to transport supplies and evacuate people from the front line. And the guys were into this work more than the girls.

Some of the guys joined the production later though – the technicians at the theatre, lighting, set designer etc– so there are some men that are involved in production.

So, this is how we almost accidentally created this performance with only women’s voices on this war. I guess there is something very strong in this piece – how women talk about the war.

What was it like to be gathered together with your colleagues for the first time after the full-scale Russian invasion started?

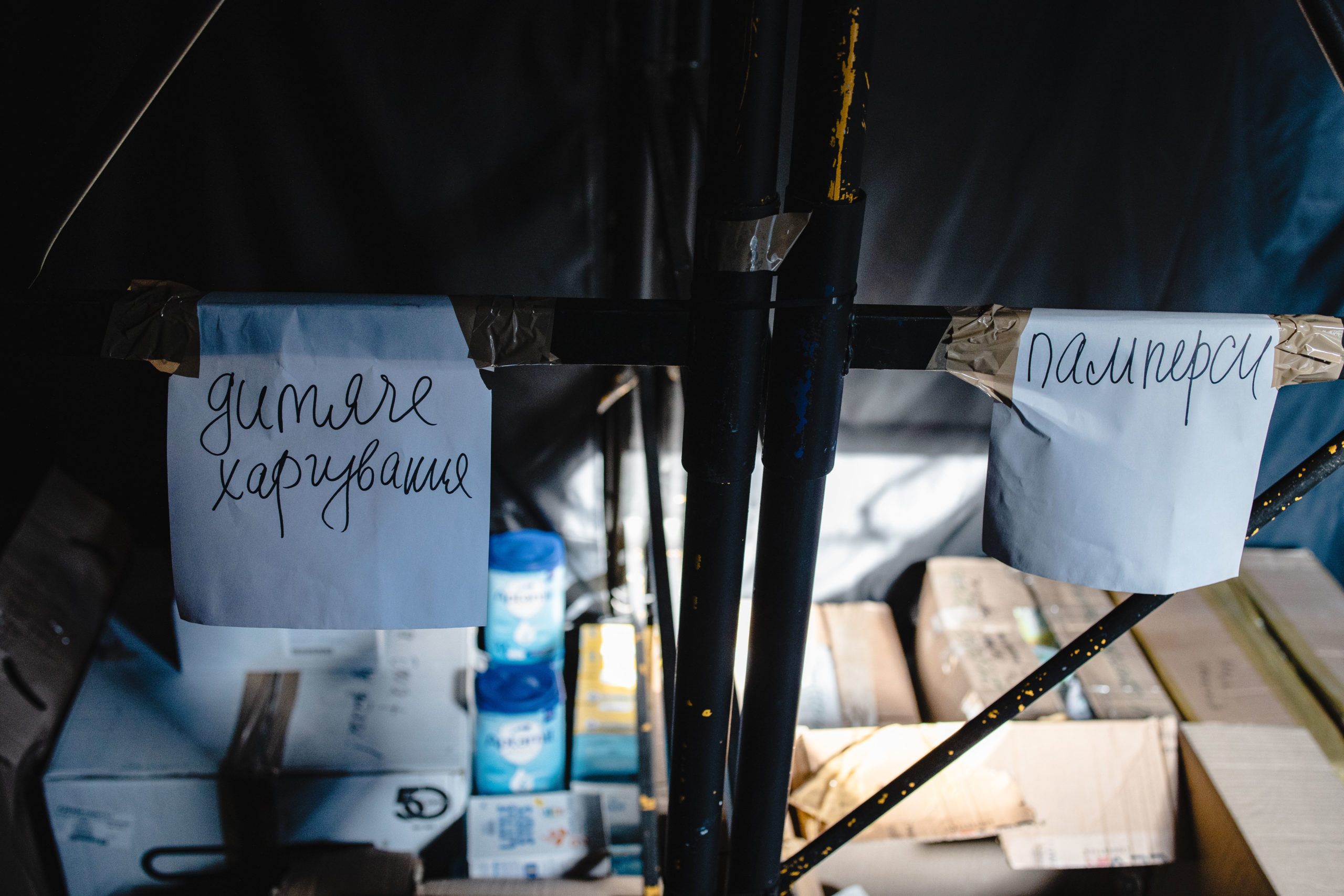

On the first morning of the full-scale invasion, we were all back in the Theatre together at 11 am. It was exactly the right place to be because we were surrounded by great people and it was easier to overcome the events happening around us together. We were just trying to understand what can we do in all of this. Two of our colleagues actually joined the army in the first days. The rest of us began work, gathering supplies and preparing the theatre to support Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs).

The previous day, we had a working meeting and Olha Puzhakovska, our Executive Director, told us that the municipality called and told her that we needed to be prepared to become a shelter.

So on that first day of the full-scale invasion, we were there trying to prepare the shelter, gathering supplies – pillows, mattresses, food, clothes… because we knew a lot of people would flee to Lviv because it is the city the furthest away from the frontline.

Where were you at the start of the full-scale Russian invasion and what did your first couple of days look like?

That first day was terrible.

I had been travelling the night before. I was in the Czech Republic and I even saw this speech of Putin in the news. On the morning of the 24th, my sister woke me up at 7 am and told me ”It started”. That sounded terrifying. Two minutes later, we heard warning sirens in the city – I had never heard them before.

I started to pack my suitcase and then I suddenly thought “and then what?” What am I going to do after I finish packing?

Later that morning when I went to the Theatre, it made me much more calm. I looked around and saw that everyone was there and understood that, okay, that’s a good sign.

On the first day, it was me that panicked the most, but on the second day, it was my sister who cried and asked me to leave and go to our mother in Poland. Who knows how we made each other calm, but we did it.

We were still trying to decide if we could get abroad because what were we supposed to do here in this war? By day three, we both had arrangements to volunteer.

My story is a lucky story. I am actually a lucky person in this because a lot of my friends have horrifying experiences not only with early waking up and warning sirens but with bombings, shootings and evacuation with one suitcase, kids and pets in overcrowded trains during long hours.

Has the Theatre’s audience changed since the start of the full-scale invasion?

Everyone changed. The audience, of course, also changed.

There were a few months when we weren’t sure if theatre was needed in society. It seemed like theatre was too much of a luxury for wartime. But step by step, our audience started coming back and suddenly we realised that we had even more people coming to the Theatre. This is also because of the people who were evacuated or relocated to Lviv. I am not sure how it was in other cities. I guess closer to the frontline it looks different. But I know how our colleagues in Kyiv and Kharkiv continued performing in the subways and shelters even during the air raid sirens.

When you see that more people are coming, it tells you that you are doing something important. This is what you need to do because people need it.

It also gave a sense of the future. After the full-scale invasion, the understanding of the “future” in Ukraine became like three days at a time because you never know what will happen. But now I have a bigger horizon.

How has this play been received by audiences in Ukraine and abroad?

It’s interesting because all audiences are similar in an empathic way, but the Ukrainian audience just understands more – every word, every joke, every reference.

Our audiences abroad have a different experience – they should read subtitles, for example. Actually, our first performance outside of Ukraine was in Avignon, France in June 2022 and it actually was without subtitles, can you imagine! But still, even then without the subtitles, people were crying and thanked us after the performance. We were so surprised because there weren’t Ukrainians besides us.

How were they able to understand anything? Yes, they get something from the news they see, but it’s this contact with our performers that is so powerful. Even people who couldn’t speak Ukrainian could understand.

Now we have had about seven performances in different countries and it has been great every time. The audience was not only satisfied, but also, perhaps, closer to us, to our performers, to this material, and maybe even closer to this moment in Ukraine.

This connection makes us feel better. It makes us feel even stronger. It made us understand that theatre can change something, and through this performance, you can remind people that this war is not only about Ukraine, it is bigger than just one country’s problem.

What should the role of theatre / the arts be during a military conflict?

There are two parts to my answer.

The first part is that culture is diplomacy. Unfortunately, [the Ukrainian authorities] don’t understand this well enough. Culture and arts is the best bridge to make partnerships.

We have so little support for cultural initiatives, and processes, especially abroad, but we need to have partners not only for weapons, we need partners in societies and within culture.

Alarmingly, it is something that Russia understands well, and they have used culture in this way throughout history.

To really make a difference, we need to have resources. Ukraine has great human resources making great contributions in different areas, history, culture, education… but we need our government to give us more support.

The second part of my answer is the role of the arts inside Ukraine.

A lot of people can’t understand the whole story of this abusive relationship between Ukraine and Russia. It even goes beyond the Soviet Union.

Unfortunately, within Ukrainian society, we have this post-colonial syndrome, and it’s so hard and frustrating to work with it. So much work needs to be done… projects, conversations… just to explain to Ukrainians why they shouldn’t be so excited for [Russian] culture.

So, to answer this question very briefly – culture has a great and underrated role during wartime. And we have to play this role for our common victory.

Since the start of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, cultural institutions abroad have faced criticism for still performing Russian music, plays and art. What is your position?

At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, a lot of people [in Ukraine] thought, uncompromisingly, that Russian culture should be cancelled in Ukraine and abroad – right now, from this day. No performances, no signing, no literature. Nothing. In the whole world. This is a naivete that a lot of us had at the time. But we were angry and categorical. This anger is from our long history with Russian culture. But our experience is not really known in the world. That’s why we looked a bit naive. But still, we got some support in this categorical asking – that is important. A lot of institutions still don’t see a problem with working with this culture – that is a pity.

What is really irritating is that institutions abroad look at this war and still try to make peace between Ukrainians and Russians using poetry or performance etc. They perhaps think of this as a great opportunity for a gesture of support. It is not.

Perhaps when I am a grandma, we will talk about our heritage and past with the Russian people, but not now. I seriously doubt that theatres and other institutions would cease to function if they halted productions of Russian culture, at least for some time – just to figure out what is wrong with it. Or at least to hear other points of view about this culture and I know that there are a lot of Ukrainian writers, musicians, and artists that are ready to explain it.

Bulgakov’s “Escape” will be performed [at Norway’s Nationaltheatret], but there is an irony that this piece from Russian culture – the same culture that forces other cultures to be refugees – will be used with the expectation that something about refugees can be learned from it. It is a really strange ironic circle.

There is a reason that Bulgakov and company are so popular… The canon of the arts and culture is something that must be agreed upon by different partners. This is critical because Russia has silenced the voice of Ukraine in this discussion for a long time.

For the past decade, we have been working hard just to shine a light on the names of different great Ukrainians who were murdered or killed under suspicious circumstances during the time when Ukraine was a part of the Soviet Union. Or those who were Ukrainians but suddenly became Russian artists, scientists, and writers because the Russian empire didn’t give any chance to develop Ukrainian culture by itself. It is about our roots which Russia has been trying to destroy for centuries. Not even everyone in Ukraine knows about them, never mind the rest of the world.

In these last two years, a lot of Ukrainians from the arts, diplomats, civil society, and even just regular people, have had this experience of having to explain the situation. It is hard work.

Unfortunately, even in our country, we have people who still don’t understand why Russian culture is dangerous… why speaking Russian in Ukraine is actually not really good because of the effect it has on everyone around you, on everything around you.

It can be frustrating and aggravating, but if we are not calm, if we respond too emotionally and with too much anger, I think it could be in vain. And it makes me more angry. Because if you want to be heard, you should keep calm, talk a lot and step by step, find some common ground.

It’s not always easy but… you still need to do it. My position is that we should talk about it, we should raise the idea that we need to rethink “the great Russian culture”. Write petitions and open letters, and explain these questions face to face. You change during this experience, and because of this experience. But also you have a chance to make a difference in this situation.

Why is it important for states like Norway to support culture and civil society in Ukraine?

I’m really impressed when smaller countries like Norway, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, which have a border with Russia, choose to be involved in this process of support and fighting on the Ukrainian side. They can understand this danger the most.

Countries from all over the world should support Ukraine because it is not only our war – stop pretending it is. This war is for civilisation and freedom, for values of it. It is so ridiculous to have this war now, in our century. How can this be? This belongs in history books. Of course, it’s not only Ukraine – other countries in the world also suffer from different conflicts right now. But I am from Ukraine and can talk about this huge catastrophe which is caused by Russia.

It’s so strange that in one part of the world, a guy like Elon Musk works on rockets to prepare to go to space, and in another part of the world people are being killed, children are being killed, soldiers are stealing everything and act with brutality in the age of gadgets and everyone can see it in a real-time.

What message do you want your audience in Norway and elsewhere to take away from the performance?

Don’t forget to be present in this reality. Don’t forget about Ukraine, because it’s not only our war. This is something bigger that could affect the whole planet.

I will also say that people should consider to explore Ukrainian culture. Not only the theatre, because our academics, scientists, historians, writers, musicians, thinkers and philosophers have a lot to offer too.

Here are a very small number of recommendations of contemporary Ukrainians who can tell you more about Ukraine: researchers Oksana Zabuzhko, Tamara Gundorova, Olena Haleta; philosopher Volodymyr Yermolenko; poets Halyna Kruk, Kateryna Kalytko, Victoria Amelina, Iryna Starovoyt; historians Serhii Plokhii, Vakhtang Kipiani, Natalia Yakovenko, Timothy Snyder (not actually Ukrainian but tells a lot about Ukraine); writers Sofiia Andrukhovych, Artem Chekh, Sergii Zhadan, Taras Prokhasko, Oleksand Mykhed, Larysa Denysenko.

Here you find a lot of strong and progressive Ukrainian voices.

Viktoria Shvydko has been the Project Manager at the Lesia Ukrainka Theater in Lviv, Ukraine (since 2017); head of NGO Art Workshop “Drabyna” (since 2016); leads the course of “Project Management in Culture” at the Ukrainian Catholic University/ UCU (since 2019).

She was also the director of the International theatre festival “Drama.UA” (2013). Twice laureate of the Best Managers of Interdisciplinary Projects award from the Lviv City Council (2018, 2020). Worked as an expert at the Ukrainian Culture Foundation (2019-2022).

Besides theatre, she is interested in interdisciplinary projects, and the development of international cooperations and communities.